Feeling ridiculed by the needling he got from former Cardinals teammates, Tim McCarver lashed out at a friend, Lou Brock, and started a fistfight with him.

On Sept. 6, 1971, during a game between the Cardinals and Phillies at Philadelphia, McCarver punched Brock in the face on the field at Veterans Stadium. Brock fought back, swinging at McCarver and landing a couple of shots, before they wrestled to the ground and were separated.

On Sept. 6, 1971, during a game between the Cardinals and Phillies at Philadelphia, McCarver punched Brock in the face on the field at Veterans Stadium. Brock fought back, swinging at McCarver and landing a couple of shots, before they wrestled to the ground and were separated.

The sight of influencers from Cardinals glory days tearing into one another was, as broadcaster Jack Buck put it, “a bit sickening,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Bob Broeg noted.

A week later, McCarver and Brock got physical again _ not in a fight, but in a jarring collision at home plate.

Sticks and stones

Brock and McCarver were integral players on Cardinals clubs that won three National League pennants and two World Series titles in the 1960s. After the 1969 season, McCarver was traded to the Phillies.

On Sept. 6, 1971, the Cardinals and Phillies had a Monday night doubleheader in the City of Brotherly Love. The opener matched pitchers Bob Gibson of the Cardinals against Rick Wise. Brock, the Cardinals’ left fielder, was in his customary leadoff spot. McCarver was the Phillies’ catcher and batted second.

The game was scoreless in the third when Brock led off with a single and stole second. After Ted Sizemore coaxed a walk, Matty Alou hit a pop fly in foul territory near the Cardinals’ dugout. McCarver dropped it for an error.

Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch, “McCarver was mad because of missing that pop-up.”

From the dugout and from the basepaths, Cardinals players heckled McCarver about botching the play.

“To say there was a little noise drifting out of the Cardinals’ dugout whenever McCarver was in earshot thereafter is to put it mildly,” the Philadelphia Daily News noted.

Cardinals first-base coach George Kissell said, “They were getting on Tim pretty good.”

Given the chance to continue his plate appearance, Alou drew a walk, loading the bases.

The next batter, Joe Torre, singled, scoring Brock and Sizemore. In his book, “Oh, Baby, I Love It,” McCarver said, “I was still burning from my error.”

When Brock got to the dugout, he continued to taunt McCarver, who had allowed more steals than any other National League catcher in 1971.

“Brock kept trying to show me up,” McCarver told the Post-Dispatch. “When Torre was on first base, Brock was yelling, ‘There he goes! There he goes!’ “

As The Sporting News noted, “The inference was McCarver’s arm was so bad that he couldn’t even throw out a slow runner like Torre.”

In his book, McCarver said, “I really snapped … I took my catching and throwing seriously.”

Unsympathetic, Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch, “It’s not anyone else’s fault that McCarver can’t throw anybody out.”

Brock said to Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Frank Dolson, “Yelling, ‘There he goes!’ shouldn’t be enough to upset McCarver, who is one of the biggest agitators in the game.”

According to George Kissell, McCarver yelled to Brock, “We’re going to stick one in your ear.”

While McCarver stewed, Wise unraveled. He gave up a RBI-double to Ted Simmons and a three-run home run to Joe Hague before being replaced by rookie Manny Muniz.

McCarver’s miscue had opened the gates to a 6-0 Cardinals lead. Adding to the embarrassment, his former teammates laughed at him, he told the Post-Dispatch.

“Guys beating you 6-0 know better than to laugh at you,” McCarver said to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Regarding Brock, McCarver told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News, “We played together long enough and he knows my boiling point … I just don’t like to be shown up.”

Macho man

Brock was the first batter for the Cardinals in the fourth. In his book, McCarver said, “I encouraged my pitcher, Manny Muniz, to intimidate Lou.”

“The first pitch crowded Brock back from the plate,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “The second pitch, another inside serve, also made him give ground.”

Brock took two or three steps in the direction of the mound. McCarver followed and heard Brock shout something to Muniz.

“I just asked Muniz, ‘What’s going on?,’ ” Brock said to the Post-Dispatch. “The kid was making me a dartboard.”

According to the Philadelphia Daily News, McCarver said Brock warned Muniz he’d come after him if another pitch came close.

“No, you’re not,” McCarver replied to Brock.

Brock turned and headed to the plate, his arms at his sides, when McCarver punched him.

“A sucker punch,” George Kissell told the Post-Dispatch.

“It was a sucker punch,” Bob Gibson agreed, “and I didn’t think much of it.”

Brock retaliated, landing a couple of punches, and then grabbed McCarver. They fell to the ground before being pulled apart by teammates.

“I’ve known McCarver since he was a kid, but I lost a lot of respect for him tonight,” Kissell said to the Post-Dispatch. “He shouldn’t let his emotions take over like that.”

What are friends for?

McCarver was ejected by plate umpire Al Barlick.

“I’m sorry the thing happened, but I felt I was right when I did it,” McCarver said to the Philadelphia Daily News.

In his book, McCarver added, “I can’t say I’m proud of what I did, but I do have to say that put in the same situation I’m sure I would react the same way.

“In moments like that, however irrationally, your instincts simply take over.”

Brock told the Philadelphia Daily News, “I was surprised Tim punched at me, but sometimes these things just explode. Tim’s too much of a pro to do what he did, but when there’s a feeling of frustration you do strange things. I have no hard feelings against him.”

McCarver said, “As far as I’m concerned, it’s all over. He’s a good friend of mine.”

Long may you run

After McCarver’s ejection, Brock continued his plate appearance versus Muniz, drew a walk and swiped second against McCarver’s replacement, Mike Ryan.

Leadng off the bottom of the fourth, Ryan was the first batter Bob Gibson faced after the fight. Gibson’s first pitch to Ryan sailed over his head.

In the sixth, Brock reached on an error, stole second and was thrown out by Ryan attempting to steal third.

An inning later, the Phillies brought in their third-string catcher, rookie Pete Koegel, after Ryan was injured. Brock swiped second _ his fourth steal of the game _ against Koegel in the eighth. Boxscore

Encore performances

The next night, Sept. 7, the Cardinals and Phillies played the series finale, and emotions remained raw.

In the first inning, Brock walked, tried to steal second and was thrown out by McCarver.

Brock noted to the Post-Dispatch, “He threw me out trying to steal, and I didn’t go punching him.”

McCarver countered to the Philadelphia Daily News, “I threw him out, and I didn’t go prancing over to the dugout like King Kong.” Boxscore

Six days later, on Sept. 13, the Phillies were in St. Louis for a two-game series.

Before the opener, Bob Broeg asked McCarver whether he regretted punching Brock. McCarver replied, “From practically the very minute I threw the punch. It was, I’m afraid, a sucker punch and I’m not proud of it.”

McCarver added, “I was agitated and apparently misunderstood something Lou had said … I like to think that out of this unfortunate flare-up we’re better friends than before. I hope so.”

In that night’s game at Busch Memorial Stadium, McCarver “was lustily booed by a crowd that used to adore him,” the Philadelphia Daily News reported.

McCarver produced three hits, scored twice and threw out Dal Maxvill attempting to steal. Boxscore

Storybook stuff

Hollywood would have a tough time coming up with a better script for what happened in the Sept. 14 series finale.

In the first inning, Brock was awarded first base on catcher’s interference when McCarver accidentally tipped his bat. Brock stole second and advanced to third on McCarver’s errant throw. Matty Alou’s infield out scored Brock.

In the ninth, the Phillies led, 5-4, but the Cardinals had Brock on third with one out and their top run producer, Joe Torre, at the plate.

Facing Chris Short, Torre hit a fly ball to medium right. Willie Montanez, a former Cardinals prospect, caught it for the second out. Brock tagged and sped for the plate, trying to score the tying run.

The throw reached McCarver on a hop. McCarver snared it and spun around to tag Brock, who was barreling toward him.

“Brock went into McCarver like a NFL bomb-squader goes into a punt returner,” Bill Conlin wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News. “The collision was tremendous, McCarver getting flipped over backwards, Brock landing in a heap on the first-base side of the plate.”

McCarver held onto the ball and Brock was called out by umpire John McSherry, ending the game. Boxscore

As Phillies players congratulated McCarver, he “broke away from them and went for Brock, grabbed his hand and shook it,” the Philadelphia Daily News reported.

“I told Lou to have a nice winter,” McCarver said.

On Sept. 3, 2001, Smith pitched a no-hitter for the Cardinals against the Padres.

On Sept. 3, 2001, Smith pitched a no-hitter for the Cardinals against the Padres. On Aug. 18, 1961, Reds manager Fred Hutchinson used a shortwave radio to communicate instructions from the bench to his third-base coach.

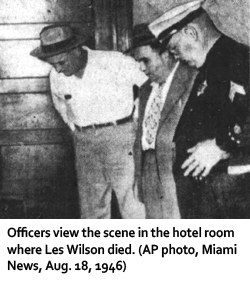

On Aug. 18, 1961, Reds manager Fred Hutchinson used a shortwave radio to communicate instructions from the bench to his third-base coach. On Aug. 17, 1946, Wilson, 35, died after a hellish night of hallucinations and destructive drinking.

On Aug. 17, 1946, Wilson, 35, died after a hellish night of hallucinations and destructive drinking. On Aug. 26, 1981, during a game at St. Louis, Templeton got booed for not hustling and reacted by making obscene gestures.

On Aug. 26, 1981, during a game at St. Louis, Templeton got booed for not hustling and reacted by making obscene gestures. In 1961, the Phillies lost 23 consecutive games _ the longest losing streak by a team since the American League joined the National League to form the majors in 1901.

In 1961, the Phillies lost 23 consecutive games _ the longest losing streak by a team since the American League joined the National League to form the majors in 1901.