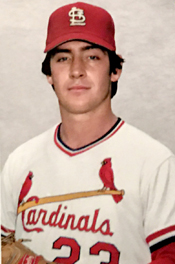

Ted Simmons was the first catcher to start All-Star Games for both the National League and American League.

Simmons was the starting catcher for the National League all-stars when he was with the Cardinals in 1978. He was the starting catcher for the American League all-stars when he was with the Brewers in 1983.

Simmons was the starting catcher for the National League all-stars when he was with the Cardinals in 1978. He was the starting catcher for the American League all-stars when he was with the Brewers in 1983.

Named an all-star eight times, Simmons played as a reserve in three games (1973, 1977 and 1981) and did not get into games after being selected in 1972, 1974 and 1979. Simmons was voted the 1979 National League starting catcher by the fans, but was unable to play because of a broken left wrist.

Ted’s turn

The Reds’ Johnny Bench was the starting catcher for the National League in every All-Star Game from 1969-77. In 1978, fans voted for Bench to be the starter again, but a bad back kept him from playing in the July 11 game at San Diego.

Bench received 2,442,201 votes in fan balloting. The other top vote-getters among National League catchers in 1978 were the Dodgers’ Steve Yeager (1,952,494), the Phillies’ Bob Boone (1,842,080) and Simmons (1,815,712).

Of the four, Simmons was producing the best. He entered the all-star break with a .311 batting average and 10 home runs. Bench (.224, 11 homers), Boone (.258, seven homers) and Yeager (.189, two homers) were not as good.

Asked for his opinion of the all-star voting by fans, Simmons told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I’d be lying if I said I did like it, but I don’t want to sound like sour-graping because everything that has come to Johnny Bench, he’s earned.”

National League manager Tommy Lasorda chose Simmons, Boone and the Braves’ Biff Pocoroba (.262, four homers) as all-star catchers, and named Simmons the starter. Before Simmons in 1978, the last catcher other than Bench to start for the National League in an All-Star Game was the Mets’ Jerry Grote in 1968.

Simmons was the first Cardinals catcher to start an All-Star Game since Walker Cooper in 1944.

Check it out

Asked about being an all-star starter, Simmons told the Post-Dispatch, “There’s nothing to match it.”

In the top of the first inning, with the Giants’ Vida Blue pitching, Simmons caught the Mariners’ Richie Zisk attempting to steal.

Batting sixth in the order, Simmons came to the plate with runners on first and second, none out, in the second against the Orioles’ Jim Palmer.

“Tough man at the plate,” said ABC-TV broadcaster Keith Jackson.

Broadcast partner Howard Cosell called Simmons “the most underpublicized exceptional hitter in baseball … I love to watch Ted Simmons hit.”

Expecting to get pitches to hit, Simmons swung exceptionally hard. “I thought I might get me a tater,” he said, explaining his home run cut.

Simmons drilled a pitch and “nearly removed the ankles from first base umpire Nestor Chylak with a nasty line drive barely outside the foul line,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

Perhaps too eager to hit another hard, Simmons struck out, making him 0-for-5 in All-Star Game plate appearances.

Simmons got another chance in the third. With two outs, he again came up with runners on first and second against the Athletics’ Matt Keough, who relieved Palmer.

Fooled by a pitch, Simmons checked his swing but still connected. The ball bounced along the third-base line, “a gentle trickle placed well enough even for Simmons, no gazelle, to leg it out,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

The infield single loaded the bases.

“My first all-star hit,” Simmons said with a grin. “I’ll take it. They could roll it out there if they wanted.”

Simmons got one more at-bat in the game. Leading off the sixth against the Brewers’ Lary Sorensen, Simmons took another big swing and hit a soft liner to the Red Sox’s Dwight Evans in right for an out.

Boone replaced Simmons in the seventh.

The National League won, 7-3, for its 15th victory in the last 16 All-Star Games. Asked about the dominance, Simmons told the Post-Dispatch, “The National League has the better players.” Boxscore and Game Video

Play to win

Two years later, in December 1980, Simmons and Sorensen were swapped in a multi-player trade between the Cardinals and Brewers.

Like Bench had done in the National League, Carlton Fisk dominated fan balloting for catcher in the American League.

Fisk was the American League all-star starting catcher every year from 1977-82, with the exception of 1979, when the Royals’ Darrell Porter started. Fisk was with the Red Sox until becoming a free agent and joining the White Sox in 1981.

In 1983, Simmons got the all-star start because he was the top vote-getter among American League catchers in fan balloting. He got the support because he was hitting .307 with six home runs at the all-star break and had played for the American League champions the previous year.

The top vote-getters were Simmons (946,254), the Tigers’ Lance Parrish (824,741), Fisk (870,342) and another former National Leaguer, the Angels’ Bob Boone (610,559).

Parrish was batting .304 with eight home runs at the all-star break. Fisk (.250, nine homers) and Boone (.251, three homers) were not as good with the bat.

Played on July 6, 1983, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, the All-Star Game had its 50-year anniversary. The National League team was managed by the Cardinals’ Whitey Herzog, who made the trade of Simmons to the Brewers.

Simmons batted twice in the game. He grounded out to pitcher Mario Soto of the Reds in the first and popped out to second against the Giants’ Atlee Hammaker in the third before being replaced by Parrish.

The American League won, 13-3, snapping an 11-game losing streak. Boxscore and Game Video

“These guys wanted to win this game,” Simmons said to The Capital Times of Madison, Wis. “You could see it in peoples’ faces. Instead of guys saying, ‘I want out of the game. I’m going to play my three innings and go,’ they wanted to stick around.

“There were a number of former National League players who had been all-stars, like Bob Boone, Dave Winfield and myself, who tried to generate that, ‘Hey, let’s win the game,’ attitude.”

On May 12, 1959, in his final at-bat of the game, Blaylock hit a two-run home run against Reds reliever

On May 12, 1959, in his final at-bat of the game, Blaylock hit a two-run home run against Reds reliever  In 1921, Hornsby was the Cardinals’ Opening Day left fielder. Before then, Hornsby had taken turns as the Cardinals’ starter at shortstop, third base, second and first.

In 1921, Hornsby was the Cardinals’ Opening Day left fielder. Before then, Hornsby had taken turns as the Cardinals’ starter at shortstop, third base, second and first. When it came time to don the shiny red fabric in a game, however, the Cardinals backed out and stuck with their flannels.

When it came time to don the shiny red fabric in a game, however, the Cardinals backed out and stuck with their flannels. In 1941, Cardinals owner Sam Breadon became convinced Vitamin B1 would enhance the performance of his players.

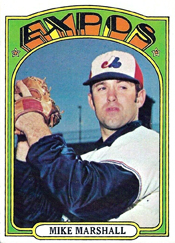

In 1941, Cardinals owner Sam Breadon became convinced Vitamin B1 would enhance the performance of his players. A right-hander with remarkable stamina, Marshall was the first relief pitcher to win a Cy Young Award. It happened in 1974, when he pitched for the Dodgers in 106 games, a major-league record for most appearances in a season by a pitcher.

A right-hander with remarkable stamina, Marshall was the first relief pitcher to win a Cy Young Award. It happened in 1974, when he pitched for the Dodgers in 106 games, a major-league record for most appearances in a season by a pitcher.