When his arm was sound, Ernie White had the talent to be an ace on the Cardinals’ pitching staff.

In June 1941, White pitched consecutive two-hit shutouts for the Cardinals against the Dodgers and Giants.

In June 1941, White pitched consecutive two-hit shutouts for the Cardinals against the Dodgers and Giants.

The back-to-back gems were the centerpieces in a stretch of 27.2 scoreless innings pitched by White, a left-hander who threw hard with an easy motion.

White earned 17 wins for the 1941 Cardinals, but arm ailments kept him from ever having another double-digit win season.

Turning pro

In 1937, White, 20, was pitching for a textile mill team in his native South Carolina when he was discovered and signed by Cardinals scout Frank Rickey, brother of club executive Branch Rickey, according to the Society for American Baseball Research.

White made his Cardinals debut in 1940 and was a prominent part of the pitching staff in 1941.

Besides White, the 1941 Cardinals pitching staff for manager Billy Southworth included Lon Warneke, Mort Cooper, Max Lanier, Harry Gumbert and Howie Krist. All posted double-digit win totals for the 1941 Cardinals.

On June 7, 1941, the Cardinals started Sam Nahem against the Giants at the Polo Grounds. A New York native, Nahem had a law degree from St. John’s University and enjoyed classical music and literature.

A right-hander, Nahem gave up three runs and was relieved by White with none out in the second. Referring to Nahem as the “boy lawyer,” J. Roy Stockton of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote dismissively, “The Brooklyn barrister didn’t have his usual stuff. Southworth told Sam to spend the rest of the afternoon reading, or something.”

White pitched eight scoreless innings of relief and got the win as the Cardinals prevailed, 11-3. Boxscore

Right stuff

White’s next appearance came on June 15 in a start versus the Dodgers in the second game of a doubleheader at St. Louis.

With two outs and none on in the third inning, pitcher Hugh Casey doubled for the Dodgers’ first hit of the game. White hit Pee Wee Reese with a pitch and walked Billy Herman, loading the bases.

“Ernie was plainly rattled,” W. Vernon Tietjen of the St. Louis Star-Times observed.

Up next was Pete Reiser, who hit a hard grounder to the right side toward Don Padgett, a hulking catcher and outfielder who was making a rare start at first base.

“Padgett threw his 215 pounds at the ball, stuck out his glove and, sure enough, when he picked himself up the ball was stuck in it,” Tietjen wrote in the Star-Times.

Padgett tossed to White, covering first, for “a sensational putout.”

In the bottom half of the third, White doubled, sparking a three-run Cardinals uprising.

White allowed one other hit, a double by Reese in the sixth, and finished with a two-hit shutout in the Cardinals’ 3-0 victory. Boxscore

Special talent

The shutout of the Dodgers ran White’s scoreless innings streak to 17.

His next appearance came June 21 in a start versus the Giants at St. Louis. White pitched another two-hit shutout. The Giants’ hits were singles by Billy Jurges in the second and Mel Ott in the fourth.

In the sixth, White stroked a RBI-single against Bill Lohrman, “a drive that took Lohrman’s cap right off his head and made him wonder, no doubt, if perhaps he wasn’t wearing his protective helmet during the wrong part of the game,” the Post-Dispatch noted. Boxscore

Four days later, on June 25, White started against manager Casey Stengel’s Braves at St. Louis.

In the second, with two outs and Braves runners on second and third, Sibby Sisti grounded a ball just out of the reach of second baseman Creepy Crespi. The hit scored both runners, ending White’s scoreless streak at 27.2 innings.

White held the Braves scoreless in the last seven innings and got the win as the Cardinals triumphed, 6-2. White also drove in one of the Cardinals’ runs with a sacrifice fly.

The win boosted White’s record for the season to 5-1 and kept the Cardinals in first place, a half-game ahead of the Dodgers. Boxscore

In the Star-Times, W. Vernon Tietjen wrote, “Everybody knows baseball pennants are rarely, if ever, won without a Paul Derringer or Bucky Walters, a Dizzy Dean, a Carl Hubbell or a Red Ruffing. Everybody knows, too, that the Cardinals are still leading this race without a substantial facsimile thereof. A good many persons strongly suspect, however, that the Cardinals have one in the making in Ernest Daniel White.”

White “has all the attributes of pitching greatness,” Tietjen declared. “His fastball, delivered with no more apparent effort than a warmup pitch, leaves batters wondering where it went.”

Career curtailed

The Cardinals (97-56) finished in second place, 2.5 games behind the champion Dodgers (100-54). White was 17-7 and was third in the National League in ERA at 2.40. He had 12 complete games and three shutouts.

An arm ailment sidelined White for part of the 1942 season, but he pitched a shutout in Game 3 of the World Series, leading the Cardinals to a 2-0 victory over the Yankees at New York. The Yankees’ lineup featured four future Hall of Famers: Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Gordon and Phil Rizzuto. Boxscore

According to the Society for American Baseball Research, White was the first pitcher to shut out the Yankees in a World Series game since the Cardinals’ Jesse Haines did it in 1926.

White had a shoulder injury in 1943. He entered the Army in January 1944, fought in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II and was discharged in January 1946.

He returned to baseball, but his arm wasn’t right. The Cardinals released White in May 1946 and he signed with the Braves, rejoining his former Cardinals manager, Billy Southworth. His final season in the majors was 1948 and he departed with a career mark of 30-21 with a 2.78 ERA.

White went on to manage teams in the farm systems of the Braves, Reds, Athletics, Yankees and Mets for 15 seasons.

In 1963, 22 years after his scoreless innings streak ended against Casey Stengel’s Braves, White became a coach on the staff of Stengel’s Mets.

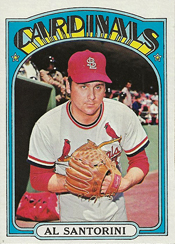

On June 11, 1971, the Cardinals acquired Santorini from the Padres for outfielder

On June 11, 1971, the Cardinals acquired Santorini from the Padres for outfielder  On June 11, 1981, Hendrick’s two-run inside-the-park home run against Valenzuela provided the margin of victory in the Cardinals’ 2-1 triumph over the Dodgers at St. Louis.

On June 11, 1981, Hendrick’s two-run inside-the-park home run against Valenzuela provided the margin of victory in the Cardinals’ 2-1 triumph over the Dodgers at St. Louis.

A switch-hitting outfielder, Scheinblum was acquired by the Cardinals to help in their quest for a division title late in the 1974 season. Scheinblum was adept at pinch-hitting and the Cardinals wanted him solely for that role.

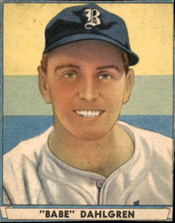

A switch-hitting outfielder, Scheinblum was acquired by the Cardinals to help in their quest for a division title late in the 1974 season. Scheinblum was adept at pinch-hitting and the Cardinals wanted him solely for that role. In 1965, the Cardinals hired Dahlgren, 52, to be director of filming. He took 16-millimeter movie film of the Cardinals at spring training and during regular-season games and then worked with manager Red Schoendienst and coaches to analyze swings of the batters.

In 1965, the Cardinals hired Dahlgren, 52, to be director of filming. He took 16-millimeter movie film of the Cardinals at spring training and during regular-season games and then worked with manager Red Schoendienst and coaches to analyze swings of the batters.