(Updated July 6, 2024)

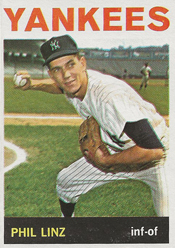

In the 1964 World Series, Phil Linz was in and out of tune against the Cardinals.

A utility player during the regular season, Linz started all seven games of the Series for the Yankees as their shortstop and leadoff batter.

A utility player during the regular season, Linz started all seven games of the Series for the Yankees as their shortstop and leadoff batter.

Linz was in the Yankees’ starting lineup against the 1964 Cardinals because shortstop Tony Kubek had a severely sprained wrist and couldn’t play.

A right-handed batter, Linz had seven hits, including two home runs, and scored five times in that Series. He also made two errors, including a Game 7 miscue that enabled the Cardinals to take the lead, and was involved in a costly misplay in Game 4.

Music man

Linz was 22 when he debuted with the Yankees in 1962. Because he played all four infield positions and the outfield, Linz became a valuable backup.

After the 1962 season, the Cardinals, seeking a shortstop, wanted Linz. According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Linz was “a No. 1 target” of general manager Bing Devine, but a deal couldn’t be worked out. (The Cardinals got Dick Groat from the Pirates instead.)

In 1964, Linz made 50 starts at shortstop, 38 at third base and three at second base for an injury-plagued Yankees team trying to stay in contention with the White Sox and Orioles for the American League pennant.

After the Yankees were swept by the White Sox in a four-game series at Chicago in August, dropping them 4.5 games out of first place, they boarded a bus for the airport. In his book “The Mick,” Yankees slugger Mickey Mantle said, “I had sneaked a couple of beers on the bus. Probably a few other guys did the same.”

Linz, seated near the back, took out a new harmonica he was learning to play and began an amateurish rendition of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

From the front of the bus, manager Yogi Berra hollered out for Linz to stop playing. Unsure what Berra said, Linz asked Mantle what he heard. In his book, Mantle, a prankster, said he replied, “Play it fast.”

As Linz tooted the tune, Berra confronted him and they argued. In the heat of the moment, Linz flipped the harmonica to Berra, who slapped at the instrument, The Sporting News reported. The harmonica struck teammate Joe Pepitone on the knee, fell to the floor and broke apart.

Linz apologized to Berra the next day and was fined $200, according to The Sporting News. Later, a harmonica company gave Linz $10,000 to endorse its product, the New York Times reported. Not a bad return for Linz on his investment in the $2.50 harmonica.

Though some initially thought the incident was an indication the Yankees were cracking under pennant pressure, the opposite occurred.

The Yankees played the incident for laughs, relaxed and surged, winning 22 of 28 games in September and finishing a game ahead of the second-place White Sox.

Borrowed bat

Linz helped the Yankees beat Bob Gibson and the Cardinals in Game 2 of the 1964 World Series. Using a bat borrowed from Mantle, Linz had three hits, a walk, a RBI and scored two runs in the Yankees’ 8-3 victory at St. Louis.

“He could play regularly on a lot of ballclubs,” Cardinals third baseman Ken Boyer told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

With the Yankees ahead, 2-1, Linz led off the seventh inning with a single against Gibson and advanced from first to third on a wild pitch. Bobby Richardson followed with a single, scoring Linz.

In the ninth, Barney Schultz, who allowed one home run in 30 appearances during the season, relieved Gibson and gave up a homer to the first batter he faced, Linz.

Linz fouled off several pitches before connecting for the home run on a fastball from the knuckleball specialist. “I guess he wasn’t afraid of me,” Linz told the Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

Botched chance

The Yankees won two of the first three games of the Series and were leading, 3-0, in the sixth inning of Game 4 when the Cardinals put runners on first and second with one out.

Dick Groat hit a grounder that had the makings of an inning-ending double play. Second baseman Bobby Richardson went to his right, gloved the ball and intended to toss it to Linz, who was moving toward the bag at second, but the ball stuck in the webbing of Richardson’s glove.

After a moment of hesitation, Richardson managed to flip the ball with his glove hand to Linz, but their timing was off.

As the ball reached Linz, baserunner Curt Flood slid into him hard and the ball fell to the ground. “On any other Sunday, Flood would have been penalized 15 yards for clipping,” Linz said to the Post-Dispatch.

All runners were safe, loading the bases, and Richardson was charged with an error. The next batter, Ken Boyer, hit a grand slam against Al Downing, erasing the Yankees’ lead and propelling the Cardinals to victory. Boxscore

“It was entirely my fault,” Richardson told The Sporting News. “Phil couldn’t possibly have handled (the throw).”

Linz said to the Post-Dispatch, “It was just as much my fault. I was a little late getting to the bag. I was on the bag, but I had to reach back for the ball. That’s when Flood hit me.”

Flood told the New York Daily News, “I was sure they had me when I saw Richardson get the ball. All I wanted to do was break up the double play. So I slid into Linz’s right leg to knock him off balance.”

Turning point

In the winner-take-all Game 7, Linz was involved in the play that turned the momentum in the Cardinals’ favor.

The game was scoreless in the fourth inning when the Cardinals put runners on first and second with no outs. Tim McCarver hit a grounder sharply to first baseman Joe Pepitone. The Yankees were expecting to turn a double play.

Pepitone threw to Linz, covering second, for the forceout, but the return throw from Linz to pitcher Mel Stottlemyre, covering first, was wild. The ball sailed wide of first base and bounced to the bunting draping the stands. Ken Boyer scored from second, giving the Cardinals a 1-0 lead.

“A good throw and we got him,” Yogi Berra told the Post-Dispatch.

Instead of two outs, none in and a runner on third, the Cardinals had one out, one in and a runner on first because of the Linz error.

Berra called Linz’s wild throw “the key play” in the game. The Cardinals went on to score three runs, including a McCarver steal of home, in the inning.

The Cardinals took a 7-3 lead into the ninth. Gibson struck out Tom Tresh before Clete Boyer hit a home run, making the score 7-4. Johnny Blanchard struck out for the second out.

Up next was Linz. He hit a Gibson fastball deep to left. Lou Brock raced back to the wall and leaped, but the ball went into the stands, where it was caught by a fan, for a home run.

Linz’s homer made the score 7-5. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane, saying he was committed to Gibson’s heart, left him in the game to face Bobby Richardson, who hat 13 hits in the Series. If Richardson reached base, slugger Roger Maris was up next, representing the potential tying run, and Keane told The Sporting News, “I would have had to get Gibson out.”

Instead, Gibson got Richardson to pop out to second baseman Dal Maxvill, and the Cardinals won the championship. Boxscore

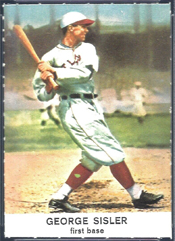

On Dec. 13, 1930, Sisler signed with the Rochester Red Wings, a Cardinals farm club, to be their first baseman after 15 seasons in the majors with the Browns, Senators and Braves.

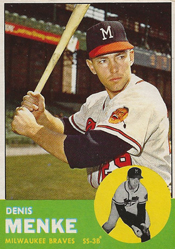

On Dec. 13, 1930, Sisler signed with the Rochester Red Wings, a Cardinals farm club, to be their first baseman after 15 seasons in the majors with the Browns, Senators and Braves. Menke was an infielder who played 13 seasons with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71, 1974) and Reds (1972-73). He also coached in the majors for 20 years.

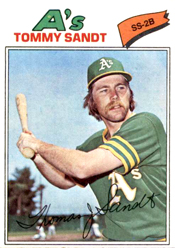

Menke was an infielder who played 13 seasons with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71, 1974) and Reds (1972-73). He also coached in the majors for 20 years. Though he never played in the majors for the Cardinals, Sandt was in their farm system after being acquired from the Athletics.

Though he never played in the majors for the Cardinals, Sandt was in their farm system after being acquired from the Athletics. On Dec. 14, 2000, the Cardinals acquired pitchers Steve Kline and Dustin Hermanson from the Expos for Tatis and pitcher Britt Reames.

On Dec. 14, 2000, the Cardinals acquired pitchers Steve Kline and Dustin Hermanson from the Expos for Tatis and pitcher Britt Reames. On Dec. 8, 1980, the Cardinals got Tenace, pitchers Rollie Fingers and Bob Shirley, and a player to be named, catcher Bob Geren, from the Padres for catchers

On Dec. 8, 1980, the Cardinals got Tenace, pitchers Rollie Fingers and Bob Shirley, and a player to be named, catcher Bob Geren, from the Padres for catchers