Kerry Robinson encountered multiple roadblocks and detours before he got a chance to play for his hometown Cardinals, completing a family quest his father began several decades earlier.

Robinson, 27, signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Dec. 7, 2000, after becoming a free agent.

Robinson, 27, signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Dec. 7, 2000, after becoming a free agent.

An outfielder with speed who hit for contact from the left side, Robinson was a St. Louis native who followed the Cardinals as a youth. His father, Rogers Robinson, spent 11 seasons as an outfielder and first baseman in the Cardinals’ farm system but never played in the majors.

Kerry Robinson was drafted and signed by the Cardinals in 1995 and played in their farm system before he was acquired by the Rays in 1997. Three years later, when he rejoined the Cardinals, Robinson was ticketed for the minor leagues, but he set his sights higher.

All in the family

Robinson was born in St. Louis in October 1973. His mother, Lois, was a special education teacher and his father, Rogers, was a pharmaceutical salesman, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Before Kerry came along, Rogers Robinson was a professional baseball player. A St. Louis native and left-handed batter, Rogers Robinson had two stints in the Cardinals’ farm system: 1957-61 and 1964-69. He had a career batting average of .298, with 1,348 hits in 1,256 games, according to baseball-reference.com.

Rogers Robinson twice reached the Class AAA level (1961 and 1964) and hit .300 or better in six seasons. He twice had seasons of more than 80 RBI and he hit 15 or more home runs five times.

Kerry Robinson attended several Cardinals games at Busch Memorial Stadium as a youth. He also developed into a standout baseball, hockey and football player at Hazelwood East High School in St. Louis. As a senior, he scored 29 goals for the hockey team and hit .557 for the baseball team.

“I’m a big hockey fan,” Robinson told the Post-Dispatch. “That’s probably my favorite sport, with football next and then baseball.”

Baseball was the sport Robinson excelled in when he went to college at Southeast Missouri State. He had a 35-game hitting streak, an Ohio Valley Conference record, his senior season.

While working toward a degree in sports management, Robinson spent time as a public relations intern for the NFL Rams, but his future was in baseball. The Cardinals chose him in the 34th round of the June 1995 amateur baseball draft.

Winding road

Robinson adapted quickly to professional baseball. In 1995, his first season, he hit .296, with 74 hits in 60 games, for Johnson City.

At spring training the next year, Robinson caught the attention of Cardinals manager Tony La Russa. “Tony said, ‘If you keep hitting like you are now, you’ll be playing here.’ ” Robinson told the Post-Dispatch.

Assigned to Peoria in 1996, Robinson hit .359 and had an on-base percentage of .422. He also had 50 stolen bases. He got promoted to Class AA Arkansas in 1997 and did well again, hitting .321, swiping 40 bases and producing an on-base percentage of .386.

At 24, his career was on the rise, but it took a turn when the Rays selected him in the American League expansion draft in November 1997.

Called up to the Rays in September 1998, Robinson went hitless in three at-bats, got waived and was claimed by the Mariners, who sent him back to the minors. Traded to the Reds in July 1999, Robinson was called up in September, used as a pinch-runner and was hitless in one at-bat.

Released by the Reds in March 2000, Robinson considered quitting, but instead signed with the Yankees, his fifth organization. He went to their Columbus farm club, hit .318 and had 37 stolen bases.

Granted free agency after the 2000 season, Robinson returned to the Cardinals, who assigned him to Class AAA Memphis.

Opportunity knocks

Though he was a non-roster player, Robinson was determined to make an impression at Cardinals spring training camp in 2001.

“My dream is to play in Busch Stadium this season, even if it’s only one game, or one at-bat,” Robinson told columnist Bernie Miklasz. “I grew up watching baseball at Busch Stadium and I want to be on that field.”

Robinson hit so well throughout spring training that after he was reassigned to the minor-league complex the Cardinals brought him back to play in big-league exhibition games.

Robinson opened the 2001 season with Memphis, batted leadoff and hit .325 in 10 games. When Mark McGwire went on the disabled list on April 18, 2001, the Cardinals called up Robinson to fill a reserve outfield spot while Craig Paquette and Bobby Bonilla moved to first base to substitute for McGwire.

Asked about getting to the big leagues with the Cardinals after his father had tried so long to do the same, Robinson told the Post-Dispatch, “I’m sort of living out his dream. I’m so proud I can do that.”

Welcome to the club

On April 24, 2001, Robinson got his first major-league hit, an infield single for the Cardinals against the Expos’ Masato Yoshii. Boxscore

A month later, Robinson got his first major-league start in the outfield and got a two-run single for his first RBI, giving the Cardinals the lead in a victory against the Brewers. Boxscore

After getting two hits in a start in center versus the Reds on June 4, 2001, Robinson was hitting .368 for the season.

“He’s got a nice calmness about him,” La Russa said. “It’s like he hasn’t been intimidated at all. He’s really had some good at-bats in clutch situations. When he puts it in play, he runs like hell.”

Bernie Miklasz noted, “Robinson is a polished hitter. He knows how to work pitchers, he can draw walks, he makes contact.”

Going deep

On June 17, 2001, Robinson entered a game against the White Sox after McGwire was ejected for arguing a called third strike. Batting in the cleanup spot, Robinson hit his first major-league home run. Boxscore

Robinson hit .285 and had 11 stolen bases for the 2001 Cardinals. In the decisive Game 5 of the National League Division Series against the Diamondbacks, he batted for McGwire in the ninth inning and executed a sacrifice bunt. Boxscore

Robinson hit .260 for the Cardinals in 2002 and .250 in 2003.

Though optioned twice to the minors during the 2003 season, Robinson came back and hit .356 for the Cardinals in August. A highlight was a walkoff home run to beat the Cubs on Aug. 28, 2003. Boxscore and Video

Bernie Miklasz wrote, “Robinson’s hunger and energy are good for the team.”

“He’s an igniter for us,” said La Russa. “He’s got a good idea about being aggressive with a ball in the strike zone, not taking those pitches.”

In March 2004, the Cardinals traded Robinson to the Padres for outfielder Brian Hunter, who was released two months later and never played a game for them.

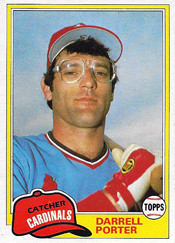

On Dec. 7, 1980, Porter agreed to a five-year, $3.5 million offer to be the Cardinals’ catcher, supplanting one of the franchise’s best players, future Hall of Famer Ted Simmons. According to the Associated Press, the deal made Porter baseball’s highest-paid catcher.

On Dec. 7, 1980, Porter agreed to a five-year, $3.5 million offer to be the Cardinals’ catcher, supplanting one of the franchise’s best players, future Hall of Famer Ted Simmons. According to the Associated Press, the deal made Porter baseball’s highest-paid catcher.

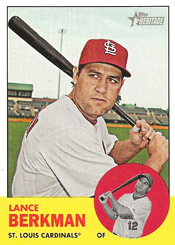

On Dec. 4, 2010, the Cardinals and Berkman agreed to terms on a one-year contract for $8 million. The Cardinals projected Berkman to be their right fielder in 2011 and join Albert Pujols and Matt Holliday in the heart of the batting order.

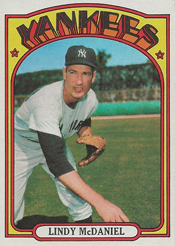

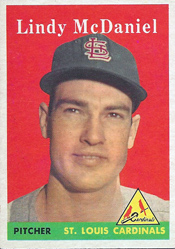

On Dec. 4, 2010, the Cardinals and Berkman agreed to terms on a one-year contract for $8 million. The Cardinals projected Berkman to be their right fielder in 2011 and join Albert Pujols and Matt Holliday in the heart of the batting order. A right-hander who developed into a quality reliever and pitched 21 seasons in the major leagues, McDaniel was 19 when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals as a teammate of Stan Musial in 1955. He was 39 when he pitched his final game with the Royals as a teammate of George Brett in 1975.

A right-hander who developed into a quality reliever and pitched 21 seasons in the major leagues, McDaniel was 19 when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals as a teammate of Stan Musial in 1955. He was 39 when he pitched his final game with the Royals as a teammate of George Brett in 1975. On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals chose Cooper in the Rule 5 draft. Cooper, 20, was the Midwest League batting champion in 1970, but the Red Sox didn’t put him on their 40-man major-league winter roster, leaving him eligible to be drafted by another organization.

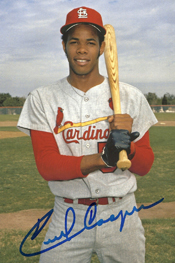

On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals chose Cooper in the Rule 5 draft. Cooper, 20, was the Midwest League batting champion in 1970, but the Red Sox didn’t put him on their 40-man major-league winter roster, leaving him eligible to be drafted by another organization.