Concerned the Cardinals had become complacent, manager Tony La Russa wanted to add infielder Ryan Theriot to the team as much for his attitude as his skills.

On Nov. 30, 2010, the Cardinals traded pitcher Blake Hawksworth to the Dodgers for Theriot.

On Nov. 30, 2010, the Cardinals traded pitcher Blake Hawksworth to the Dodgers for Theriot.

The Cardinals projected Theriot to be their 2011 shortstop, replacing Brendan Ryan, and bat leadoff.

“One of the things we wanted to do was find someone who fit in very well with the club, someone who played hard, and I think Theriot represents those characteristics,” Cardinals general manager John Mozeliak told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Though Theriot eventually got shifted from shortstop to second base by the Cardinals, he and another key acquisition, outfielder Lance Berkman, helped change the club vibe in a 2011 season that concluded with a World Series title.

Cardinals rival

Theriot played for 2000 College World Series champion Louisiana State and was chosen by the Cubs in the third round of the 2001 June amateur baseball draft.

A right-handed batter who hit for average, Theriot made his debut in the majors in September 2005 with the Cubs. Two years later, he became their starting shortstop, replacing Cesar Izturis.

Playing for manager Lou Piniella, Theriot helped the Cubs reach the postseason in 2007 and 2008. He had 30 doubles in 2007, and he hit .307 in 2008.

Theriot remained the Cubs’ shortstop when they opened the 2010 season, but in May he was shifted to second base and rookie Starlin Castro took over at short. On July 31, 2010, the Cubs traded Theriot to the Dodgers and he finished the season as their second baseman.

Culture change

Theriot preferred to play shortstop and the Cardinals were in the market for one. The Cardinals, who failed to qualify for the postseason in 2010, wanted a shortstop to replace Brendan Ryan, “whose defensive wizardry failed to compensate for what manager Tony La Russa and the Cardinals’ front office saw as maddening inconsistency,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

Ryan hit .223 in 2010.

When the Dodgers signed free-agent infielder Juan Uribe in November 2010, Theriot became expendable.

According to the Post-Dispatch, the Cardinals had been in talks with the Rays about acquiring their shortstop, Jason Bartlett, but the Rays wanted a package of prospects and Mozeliak was more agreeable to dealing a player, such as Hawksworth, from the big-league roster.

Mozeliak described Theriot as “a winning-type player, someone who understands the game, who can be used in a variety of roles and who has the ability in a lot of different places in the lineup.”

Post-Dispatch columnist Bernie Miklasz noted La Russa “coveted” Theriot’s “fierce competitiveness to sharpen the team’s edge.”

“La Russa wanted Theriot’s hard-wired personality, and the Cardinals believed they’d receive enough offense from Theriot to make up for his shaky defense,” Miklasz wrote.

A week after acquiring Theriot, the Cardinals signed Berkman, a free agent, to bolster a club that had missed the postseason in three of the past four years.

Mozeliak said, “Last season, if we were down, 4-2, in the seventh inning, the game was over. We thought Berkman and Theriot could help us change the culture.”

Cardinals first baseman Albert Pujols called Theriot a “smart player” and someone “who knows how the game should be played.”

That’s a winner

Theriot, 32, signed for $3.3 million to play shortstop for the 2011 Cardinals. “For me, shortstop is the most comfortable,” Theriot said. “It’s what I grew up playing.”

Theriot hit .322 for the Cardinals in April, but he made errors in his first two games. When he made a couple of more errors early in May, giving him eight after one month of play and dropping his fielding percentage to .927, skeptics wondered whether Theriot was right for the job.

Responding to the criticism, La Russa told the Post-Dispatch, “I look at the whole player. He plays his butt off every day. Overall he’s been a significant plus for us. So, he’s made some errors … I’ve equated him a lot to David Eckstein in the way he never takes a day off, never takes an inning off, never takes an at-bat off. Those kinds of guys over six months will do a lot of extra things for you.”

Theriot went on a 20-game hitting streak from May 15 to June 7, raising his batting average for the season to .298.

A month later, he went into a slump, with one hit in 27 at-bats, and his batting average dropped to .263 on July 28. Theriot’s on-base percentage also plummeted to .311, poor for a leadoff batter.

On July 31, the Cardinals acquired Rafael Furcal from the Dodgers and made him the shortstop and leadoff batter. Theriot was shifted to second base, platooning with left-handed batter Skip Schumaker.

Furcal was a catalyst in the Cardinals’ late run to qualify for a postseason berth as a wild-card entry.

Theriot finished the regular season with 26 doubles and a .271 batting mark. He hit .310 against left-handers and .281 from the leadoff spot. He made 87 starts at shortstop and 17 at second base.

In the 2011 National League Division Series, Theriot had six hits in 10 at-bats versus the Phillies. He batted .077 in the World Series against the Rangers, but he did drive in a run in the 10th inning of the Cardinals’ comeback classic in Game 6. Boxscore

After the season, Theriot became a free agent and signed with the Giants. He was the Opening Day second baseman for the 2012 Giants, but eventually was supplanted by Marco Scutaro, who hit .500 (14-for-28) against the Cardinals in the National League Championship Series.

The 2012 Giants went on to become World Series winners. Theriot, who started 81 games at second base for the Giants and hit .270 for the season, got World Series championship rings in each of his last two seasons in the majors.

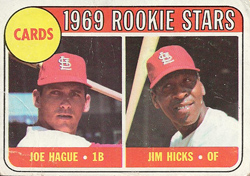

Though he hit for power and average in the minors, Hicks primarily was a reserve player in brief stints in the majors with the White Sox, Cardinals and Angels. A right-handed slugger, he began the 1969 season as a backup outfielder for the Cardinals.

Though he hit for power and average in the minors, Hicks primarily was a reserve player in brief stints in the majors with the White Sox, Cardinals and Angels. A right-handed slugger, he began the 1969 season as a backup outfielder for the Cardinals. On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Moe Drabowsky from the Orioles for infielder Jerry DaVanon.

On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Moe Drabowsky from the Orioles for infielder Jerry DaVanon. On Nov. 29, 1950, Marion was chosen by Cardinals owner Fred Saigh to replace manager Eddie Dyer, who resigned. The hiring came two days before Marion turned 33.

On Nov. 29, 1950, Marion was chosen by Cardinals owner Fred Saigh to replace manager Eddie Dyer, who resigned. The hiring came two days before Marion turned 33. On Aug. 3, 1979, La Russa was 34 when he managed his first game in the majors for the White Sox. On Oct. 29, 2020, La Russa was 76 when he was named White Sox manager for a second time.

On Aug. 3, 1979, La Russa was 34 when he managed his first game in the majors for the White Sox. On Oct. 29, 2020, La Russa was 76 when he was named White Sox manager for a second time. Flood hadn’t played in a game since Oct. 2, 1969, with the Cardinals. Five days later, the Cardinals

Flood hadn’t played in a game since Oct. 2, 1969, with the Cardinals. Five days later, the Cardinals