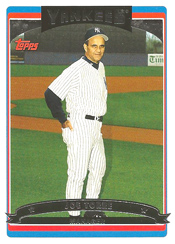

Joe Torre thought when he got fired by the Cardinals his career as a manager was finished. He never figured the best was yet to come.

On Nov. 2, 1995, Torre, 55, was hired to manage the Yankees, who, to his surprise, approached him about replacing Buck Showalter.

On Nov. 2, 1995, Torre, 55, was hired to manage the Yankees, who, to his surprise, approached him about replacing Buck Showalter.

Five months earlier, when the Cardinals gave up on him, it seemed to Torre it was like three strikes and you’re out. He’d managed three teams, Mets, Braves and Cardinals, and was fired by each. His teams never won a World Series title and only one, 1982 Braves, qualified for the postseason.

After the Cardinals fired him in June 1995, Torre, who also played 18 years in the majors, including six with the Cardinals, said he planned to return to broadcasting, a role he did with the Angels before the Cardinals hired him.

Instead, given the chance to manage the Yankees, he transformed from a retread into a Hall of Famer.

Free agent

Hired by the Cardinals in August 1990 to replace Whitey Herzog, who quit, Torre had winning records in 1991, 1992 and 1993, but the club finished 53-61 in 1994 and Torre’s friend, general manager Dal Maxvill, was fired and replaced by Walt Jocketty. When the Cardinals staggered to a 20-27 start in 1995, Jocketty fired Torre.

In his book, “Chasing the Dream,” Torre said, “I planned to go back to broadcasting. The politics and players’ attitudes in St. Louis had left a sour taste in my mouth anyway. I thought I was treated shabbily by the Cardinals, though I never said anything to embarrass the organization, even when I was fired.”

Torre and his wife, Ali, moved to Cincinnati to be close to her family. In October 1995, the Yankees called and asked him to interview for their general manager job, which opened when Gene Michael stepped down.

After the interview, Torre withdrew from consideration because he said he wasn’t interested in what the role required, but he’d made a favorable impression on Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

Friends in high places

On Oct. 23, 1995, the Yankees named Bob Watson as their general manager. Watson’s last three seasons as a player were with the Braves when Torre was manager. Torre entrusted him to serve as an unofficial assistant coach, an opportunity that helped prepare Watson for the next step in his baseball career.

The Yankees in 1995 had qualified for the postseason for the first time since 1981. The success heightened the popularity of manager Buck Showalter, whose contract was due to expire on Nov. 1.

Steinbrenner said Showalter wanted a three-year contract. Steinbrenner offered two years at $1.05 million, but Showalter rejected it “because it contained stipulations he didn’t like,” The Sporting News reported.

One stipulation was the Yankees wanted him to fire coach Rick Down.

When Showalter and the Yankees couldn’t agree on terms, Steinbrenner decided to let the contract expire and hire someone else.

Steinbrenner and Watson agreed on who should be the top choice: Torre.

Will to win

In his book, Torre said Steinbrenner called him and said, “You’re my man.”

A couple of days later, on Nov. 1, 1995, Torre met with Steinbrenner and Watson in Tampa. Torre was offered the same contract Showalter had rejected: two years at $1.05 million. The deal was for a salary of $500,000 the first year and $550,000 the next, and Torre was told it was non-negotiable. “It was a pay cut for me,” Torre said in his book. “I’d earned $550,000 with St. Louis.”

Torre understood the risks of working for Steinbrenner but was unfazed. “I knew George was willing to spend the money to win a world championship,” Torre said. “It wasn’t like St. Louis, where sometimes I had felt as if I were in a fight with my fists while the other guy had a gun.”

Torre accepted and the next day he was introduced at a press conference in New York as Yankees manager. He joined Casey Stengel, Yogi Berra and Dallas Green as men who managed both the Yankees and Mets.

Quality credentials

Watson said the Yankees also considered Butch Hobson, Gene Lamont, Chris Chambliss and Sparky Anderson for the manager job, but acknowledged Torre was the only candidate who met in person with club officials, Newsday reported.

Torre “had most of the qualities I was looking for in a manager,” Watson said. “He was a man I could communicate with. He’s not predictable. He’ll gamble a little bit.”

Torre told the New York Daily News, “I want a team that disrupts. I want an aggressive team. Speed never really goes into a slump.”

With characteristic self-deprecation, he added, “The way I ran as a player enables me to want someone who doesn’t run the way I did.”

Bill Madden of the New York Daily News called Torre “bright and personable” and noted he “has a natural presence that commands respect.” Torre’s downside was being “too laid back” and having a tendency to “move players out of position,” Madden added.

Pitcher Bob Tewksbury, whose best seasons occurred while Torre was managing the Cardinals, said, “He did more for me than any manager I played for. He believed in me. He has a way of relating to players that works. I don’t think you can take Joe Torre, the manager of the Cardinals, and predict how he’s going to manage the Yankees. His personnel will be different with the Yankees and he’ll adjust.”

Right stuff

Tewksbury was correct.

Torre guided the Yankees to six American League pennants and four World Series crowns., groomed Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera into Hall of Famers, and connected with consistent standouts such as David Cone, Tino Martinez, Paul O’Neill, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada and Bernie Williams.

Torre and the Yankees split after the 2007 season and he finished his managerial career with the Dodgers. His final postseason triumph came in 2009 when the Dodgers swept the Cardinals in the National League Division Series.

In 29 years as a manager in the majors, Torre had a record of 2,304-1,982. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in December 2013 along with peers Bobby Cox and Tony La Russa.

On Dec. 14, 1970, Hill, 25, drowned while swimming in the sea in Venezuela.

On Dec. 14, 1970, Hill, 25, drowned while swimming in the sea in Venezuela. He was a highly regarded prospect who experienced personal tragedy soon after he got to the majors.

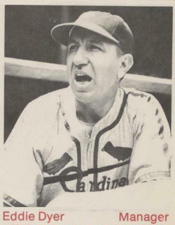

He was a highly regarded prospect who experienced personal tragedy soon after he got to the majors. On Oct. 16, 1950, after five seasons as Cardinals manager, Dyer, 51, resigned rather than wait for club owner Fred Saigh to make a change.

On Oct. 16, 1950, after five seasons as Cardinals manager, Dyer, 51, resigned rather than wait for club owner Fred Saigh to make a change.

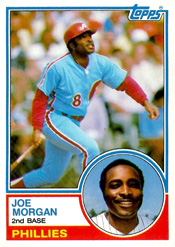

A second baseman who began his big-league career with the Houston Colt .45s, Morgan spent his prime years as an integral member of championship Reds teams in the 1970s.

A second baseman who began his big-league career with the Houston Colt .45s, Morgan spent his prime years as an integral member of championship Reds teams in the 1970s.