If not for the effective relief pitching of Ron Perranoski, the Cardinals, not the Dodgers, might have won the 1963 National League pennant and given Stan Musial a chance to end his playing career in a World Series.

A left-hander, Perranoski played 13 years in the majors and coached another 17 years in the big leagues.

A left-hander, Perranoski played 13 years in the majors and coached another 17 years in the big leagues.

In 1963, the Dodgers held a one-game lead over the Cardinals heading into a three-game series at St. Louis. The Dodgers swept, with Perranoski earning a save and a win, and went on to clinch the pennant.

Cool and collected

Born and raised in New Jersey, Perranoski early on displayed poise and a calm disposition on the mound. “As a high school pitcher, mom and dad used to complain they couldn’t tell whether I’d won or lost by the way I looked when I came home,” Perranoski told the Los Angeles Times.

He enrolled at Michigan State and was a roommate and teammate of Dick Radatz, who, like Perranoski, would become a dominant reliever in the majors.

Perranoski signed with the Cubs in June 1958. After two years in their farm system, the Cubs traded Perranoski to the Dodgers for infielder Don Zimmer. Former Cubs manager Bob Scheffing, who considered Perranoski a top prospect, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “If I were still with Chicago, they’d have made that Perranoski trade over my dead body.”

After posting a 2.58 ERA in the minors in 1960, Perranoski pitched well at spring training in 1961 and earned a spot on the Dodgers’ Opening Day roster. His first big-league save came on April 18, 1961, against the Cardinals. In what the Los Angeles Times described as “a brilliant piece of relief pitching,” Perranoski retired Bill White with the bases loaded in the eighth, and set down the side in order in the ninth. Boxscore

A year later, in May 1962, Musial’s single off a curve from Perranoski gave Musial his 3,431st hit and moved him ahead of Honus Wagner for No. 1 on the National League career hit list.

Reliable relief

In 1963, there were no better relievers in the majors than the former Michigan State roommates, Perranoski and Radatz. Perranoski was 16-3 with 21 saves and a 1.67 ERA for the 1963 Dodgers. Radatz, a hulking right-hander nicknamed “The Monster,” was 15-6 with 23 saves and a 1.97 ERA for the 1963 Red Sox.

The Los Angeles Times described Perranoski as the “miracle man of the 1963 Dodgers. If the others can’t win them, he will.”

With Perranoski in the bullpen, and Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Johnny Podres heading the starting rotation, the Dodgers had the best ERA in the National League in 1963, but the Cardinals kept pace with them.

Entering the Sept. 16-18 series at St. Louis, the Dodgers were 91-59 and the Cardinals were 91-61.

The Cardinals became sentimental favorites when Musial, their 42-year-old icon, revealed in August that 1963 would be his last year as a player. Musial had played in four World Series, but none since 1946, and many were pulling for the Cardinals to overtake the Dodgers and give Musial a storybook finish to his career.

Naturally, Perranoski and the Dodgers had other ideas.

Impressive pitching

Podres and Ernie Broglio were the starting pitchers for the opening game of the Dodgers-Cardinals series. The score was tied at 1-1 when the Dodgers struck for two runs in the top of the ninth against relievers Bobby Shantz and Ron Taylor.

Perranoski replaced Podres for the bottom of the ninth and got the save, retiring Dick Groat, Musial and Ken Boyer in order. Boxscore

“Podres still can make the big haul and Perranoski puts the cash in the bank,” the Post-Dispatch noted.

Said Podres: “I knew Perranoski would be ready. He’s the best relief pitcher there is.”

When Koufax pitched a four-hit shutout against the Cardinals in Game 2, the Dodgers moved three ahead in the standings. Boxscore

The Cardinals needed to win the series finale to keep their pennant hopes from fading.

Great escape

The starting pitchers for Game 3 were the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson and the Dodgers’ Pete Richert. In the eighth, with the Cardinals ahead, 5-1, the Dodgers scored three times against Gibson and Shantz, getting within a run.

Dodgers manager Walter Alston picked Perranoski to pitch the bottom of the eighth and he retired the side in order. In the ninth, Dick Nen, in his debut game, hit a home run against Ron Taylor, tying the score at 5-5.

Perranoski again retired the Cardinals in order in the ninth, but he got into trouble in the 10th. Dick Groat led off and tripled. “I tried to jam Groat with a fastball, but I got it up,” Perranoski told the Post-Dispatch.

Alston went to the mound for a conference with Perranoski. Don Drysdale was throwing in the Dodgers’ bullpen, but Alston later said, “I was going all the way with Perranoski.”

Alston asked Perranoski whether he wanted to pitch to the next batter, Gary Kolb, or load the bases with intentional walks to set up a forceout at the plate. Perranoski opted to pitch to Kolb, a left-handed batter who entered the game in the seventh to run for Musial.

“I wasn’t too alarmed because I knew I had control and I felt if I got beat they’d have to beat me on my best pitch,” Perranoski told the Los Angeles Times.

Kolb struck out looking at an outside curve.

Perranoski gave intentional walks to Ken Boyer and Bill White, loading the bases for Curt Flood. “I knew Flood was a tough cookie to double up, but I had to get him to hit the ball on the ground,” Perranoski said.

After jamming Flood with an inside fastball, Perranoski got him to chase an outside curve. Flood hit a bouncer to shortstop Maury Wills, who threw to the plate to get the forceout on Groat.

With two outs and the bases loaded, Mike Shannon came up next. “I knew Shannon was a good fastball hitter,” Perranoski said.

Perranoski started him off with a sinker. Shannon hit a tapper to third. Jim Gilliam fielded the ball and threw to first in time to retire Shannon and end the threat.

Long career

The Cardinals didn’t get another good scoring opportunity against Perranoski. In the 13th, the Dodgers scored an unearned run against Lew Burdette. Perranoski retired the Cardinals in order in the bottom half of the inning, sealing the 6-5 Dodgers win and crushing the Cardinals’ pennant chances. Boxscore

With six innings of scoreless relief, Perranoski got his 16th win of the season. “This was the biggest game I ever pitched,” he said. “It’s got to be my biggest thrill.”

Cardinals manager Johnny Keane said, “I’ve never seen anyone get them out better than he does time after time.”

The Dodgers went on to clinch the pennant, finishing at 99-63. The Cardinals placed second at 93-69.

Perranoski pitched in three World Series for the Dodgers. He also pitched for the Twins, Tigers and Angels, leading the American League in saves in 1969 and 1970.

Perranoski was Dodgers pitching coach from 1981-94. Among the pitchers he helped develop were Orel Hershiser, Rick Sutcliffe and Fernando Valenzuela.

He also mentored reliever Tom Niedenfuer. According to the Los Angeles Times, Perranoski “sort of adopted him.”

“Possibly the greatest thing Perranoski did for Niedenfuer was tell him to throw with the same motion as Goose Gossage,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

In 1985, Niedenfuer led the Dodgers in saves, but in Game 5 of the National League Championship Series he gave up a walkoff home run to the Cardinals’ Ozzie Smith. In the next game, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda ordered Perranoski to tell Niedenfuer to pitch to Jack Clark with two on, two outs and a base open, and Clark hit a home run, carrying the Cardinals to the pennant.

An outfielder and left-handed batter, Johnstone played 20 seasons in the majors for eight teams.

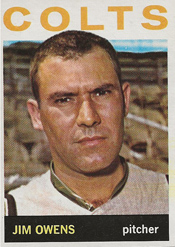

An outfielder and left-handed batter, Johnstone played 20 seasons in the majors for eight teams. Once a prized Phillies prospect, Owens clashed with the club’s management and created havoc as part of a group of hard-drinking pitchers dubbed the Dalton Gang.

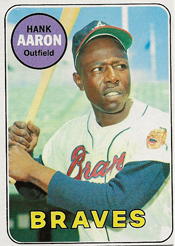

Once a prized Phillies prospect, Owens clashed with the club’s management and created havoc as part of a group of hard-drinking pitchers dubbed the Dalton Gang. On July 28, 1970, Gibson threw a knuckleball in a game for the first time. The batter he threw it to was Aaron.

On July 28, 1970, Gibson threw a knuckleball in a game for the first time. The batter he threw it to was Aaron.

On Sept. 28, 1970, the Cardinals acquired Norman on waivers from the Dodgers. The move was made to get a jump on building a bullpen for the following season.

On Sept. 28, 1970, the Cardinals acquired Norman on waivers from the Dodgers. The move was made to get a jump on building a bullpen for the following season.