A kind gesture by Reds manager Sparky Anderson turned a disappointing ending into an uplifting moment.

On Oct. 15, 1970, the Reds were one out away from being eliminated in the decisive game of the World Series against the Orioles. At a time when some managers might be feeling despair, Anderson was feeling compassion.

The Reds’ Pat Corrales, a loyal, seldom-used backup catcher who had experienced personal tragedy, never had played in a World Series game. Realizing Corrales might never get another chance, and knowing how meaningful it would be to him, Anderson sent him to bat for one of the Reds’ hottest hitters, Hal McRae.

In his brief plate appearance, Corrales made the last out of the 1970 World Series, but the result didn’t matter. Unlike Hall of Famers such as George Sisler and Ernie Banks, Corrales had gotten to play in a World Series, and Anderson, in his first season as a big-league manager, had enhanced his growing reputation by being a considerate leader.

Three years earlier, Anderson and Corrales were in the Cardinals’ system _ Anderson as a manager looking to move up in rank, and Corrales as a catcher looking to show he could hit.

Cardinals connections

Anderson joined the Cardinals as a minor-league manager in March 1965. Corrales was acquired by the Cardinals in a trade with the Phillies in October 1965. Cardinals general manager Bob Howsam dealt Bill White, Dick Groat and Bob Uecker to the Phillies for Alex Johnson, Art Mahaffey and Corrales.

After managing St. Petersburg to a 91-45 record in 1966, Anderson was looking to manage the Cardinals’ top farm club, Tulsa, in 1967, but Stan Musial, who’d replaced Howsam as general manager, gave the job to Warren Spahn. Anderson was assigned to manage Modesto. After the 1967 season, Howsam, who had become general manager of the Reds, hired Anderson to manage in the Cincinnati farm system. Two years later, he became manager of the Reds.

Corrales, 25, spent the 1966 season as backup to Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver, but got into a mere 28 games and hit .181. “I’m probably the only guy in the league who has thrown out more runners than he has hits,” Corrales told The Sporting News.

Actually, it was a tie. Corrales finished the 1966 season with 13 hits and threw out 13 runners attempting to steal.

Afterward, Corrales reported to the Cardinals’ Florida Instructional League team to work on his hitting. The manager was George Kissell and Sparky Anderson was his assistant. When Corrales injured a knee, the Cardinals acquired Johnny Romano from the White Sox to be McCarver’s backup. Corrales played the 1967 season at Tulsa for Spahn, and hit .274 in 130 games.

Howsam and the Reds knew their top prospect, Johnny Bench, would be the starting catcher in 1968, replacing Johnny Edwards, and viewed Corrales as a potential backup. On Feb. 8, 1968, Howsam acquired Corrales for the second time, trading Edwards to the Cardinals for him and Jimy Williams.

Devastating death

Corrales began the 1968 season with the Reds’ farm team at Indianapolis, managed by Don Zimmer, and hit .273 in 77 games. He got called up to the Reds in July to provide relief for Bench, who started 81 games in a row. On July 29, 1968, Corrales was the catcher when the Reds’ George Culver pitched a no-hitter against the Phillies.

Corrales impressed Reds management and was popular with teammates. Asked about Corrales, Pete Rose told The Sporting News, “There’s a man who can do it all. He knows what’s going on out there every minute. Corrales makes a pitcher think on the mound.”

Corrales stuck with the Reds in 1969.

On July 22, 1969, Corrales’ wife, Sharon, 27, gave birth to a son at 5:02 a.m. at Cincinnati’s Christ Hospital. It was the couple’s fourth child. They had three daughters, the oldest, 5, and twins, 3.

Ten hours later, Sharon died in the hospital. The cause was pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lungs, the Dayton Daily News reported.

Corrales returned to the Reds a week after Sharon’s funeral. Several teams raised money for an education fund for Corrales’ children, Newsday reported. Among the fund-raisers were the Orioles. According to The Sporting News, Orioles players donated money from fines collected by their clubhouse kangaroo court. Orioles wives raised funds with a bake sale and paper flower sale.

After the 1969 season, the Reds changed managers, replacing Dave Bristol with Sparky Anderson. At spring training in 1970, Anderson said, “In Corrales, I’ve got the best backup catcher in baseball.”

People skills

Corrales hit .236 in 43 games for the 1970 Reds, who finished first in the West Division. Against the Cardinals, he hit .417 (5-for-12).

In the National League Championship Series, the Reds swept the Pirates, and Corrales didn’t play. In the World Series, the Orioles won three of the first four games, and again Corrales didn’t play.

In Game 5 at Baltimore, the Orioles led, 9-3, entering the ninth. Sparky Anderson called to the bullpen, where Corrales had been catching throws from Reds relievers, and told him to come to the dugout.

According to the Dayton Daily News, Anderson approached Hal McRae, who hit .455 in the World Series, and told him, “Unless somebody gets on base before you, I’m going to have Pat hit for you. It’s not a reflection on you. I want him to have a chance to get his name in a World Series box score.”

McRae told Anderson he understood.

After starter Mike Cuellar retired the first two batters, Bench and Lee May, Anderson sent Corrales to the plate. Anderson, who played one season in the majors and 10 in the minors, appreciated a role player such as Corrales, who lived in Bench’s shadow.

“Anyone who plays his heart out for you all year deserves a chance to play in a World Series,” Anderson told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Corrales has done that for us and I wasn’t going to let this chance get away.”

To the Dayton Daily News, Anderson said, “I wasn’t being sentimental. I was being honest. I’d have let him down by not letting him bat.”

Corrales hit Cuellar’s first pitch to third. Brooks Robinson fielded it and threw to first for the final out, clinching the championship for the Orioles. Boxscore

Explaining why he swung away, Corrales told the Cincinnati Enquirer, “I wasn’t going to take nothing when I went up there. I wanted to hit.”

Regarding the move by Anderson, Corrales told Newsday, “I appreciate he thought of giving me the chance.”

Ritter Collett of the Dayton Journal Herald called Anderson’s action “a considerate gesture, like a coach getting his seniors into the final game.”

Wells Twombly wrote in The Sporting News, “It was a charming gesture, full of good, rich schmaltz. The lovely thing about Sparky is he dares to be corny in a violently cynical age.”

Said Anderson, “The World Series still is the biggest sporting event in America. That’s why I wanted to make sure Pat had a chance to get his name in a box score. It means a lot to a guy.”

Corrales never played in another World Series. He did coach in five World Series (1991, 1992, 1995, 1996 and 1999) for the Braves on the staff of manager Bobby Cox.

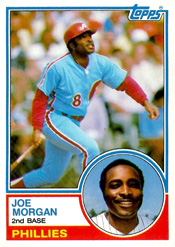

A second baseman who began his big-league career with the Houston Colt .45s, Morgan spent his prime years as an integral member of championship Reds teams in the 1970s.

A second baseman who began his big-league career with the Houston Colt .45s, Morgan spent his prime years as an integral member of championship Reds teams in the 1970s. A left-hander, Perranoski played 13 years in the majors and coached another 17 years in the big leagues.

A left-hander, Perranoski played 13 years in the majors and coached another 17 years in the big leagues. An outfielder and left-handed batter, Johnstone played 20 seasons in the majors for eight teams.

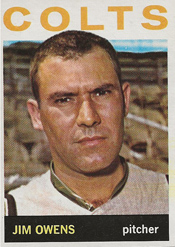

An outfielder and left-handed batter, Johnstone played 20 seasons in the majors for eight teams. Once a prized Phillies prospect, Owens clashed with the club’s management and created havoc as part of a group of hard-drinking pitchers dubbed the Dalton Gang.

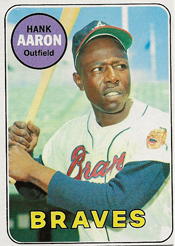

Once a prized Phillies prospect, Owens clashed with the club’s management and created havoc as part of a group of hard-drinking pitchers dubbed the Dalton Gang. On July 28, 1970, Gibson threw a knuckleball in a game for the first time. The batter he threw it to was Aaron.

On July 28, 1970, Gibson threw a knuckleball in a game for the first time. The batter he threw it to was Aaron.