After playing a twi-night doubleheader in St. Louis, the Dodgers were grateful to arrive alive for their afternoon game in Chicago the next day.

On Sept. 15, 1945, a passenger train carrying members of the Dodgers from St. Louis to Chicago collided with a gasoline tanker truck at a road crossing in Manhattan, Ill.

On Sept. 15, 1945, a passenger train carrying members of the Dodgers from St. Louis to Chicago collided with a gasoline tanker truck at a road crossing in Manhattan, Ill.

The locomotive engineer was killed in the crash. The train’s fireman was burned, but survived with assistance from the Dodgers’ trainer.

None of the Dodgers were badly injured.

Scheduling conflicts

After playing a doubleheader at Cincinnati on Tuesday, Sept. 11, the Dodgers arrived by train in St. Louis the morning of Wednesday, Sept. 12, and were scheduled to play a doubleheader that evening versus the Cardinals.

The Cardinals won the opener but the second game was called off because of rain. Another doubleheader was scheduled for Thursday, Sept. 13, but rain wiped out both games. The games were rescheduled for Friday, Sept. 14, which was supposed to be a travel day for the Dodgers.

Dodgers manager Leo Durocher requested day games for the Sept. 14 doubleheader so that his club would have time to rest after traveling to Chicago for their day game on Saturday, Sept. 15, against the Cubs, but Cardinals owner Sam Breadon scheduled the Sept. 14 doubleheader to start at 5 p.m.

The Dodgers sent Les Webber, their starting pitcher for the Sept. 15 day game, to Chicago ahead of time.

The weather in St. Louis was chilly and damp on Sept. 14 and the doubleheader attracted a mere 2,103 paid customers, but both games were played. The Dodgers swept. Boxscore and Boxscore

The setbacks dropped the Cardinals 3.5 games behind the league-leading Cubs.

All aboard

After the Sept. 14 doubleheader, the eight starting position players for the Dodgers departed for Chicago on one train and the remainder of the club left on the midnight train, the Wabash Limited.

The same eight position players had started both games of the Sept. 14 doubleheader. They were Eddie Stanky, Goody Rosen, Augie Galan, Dixie Walker, Ed Stevens, Frenchy Bordagaray, Tommy Brown and Mike Sandlock.

Boarding the midnight train were manager Leo Durocher, coaches Chuck Dressen and Red Corriden, traveling secretary Harold Parrott, trainer Harold Wendler, and players Hal Gregg, Cy Buker, Vic Lombardi, Babe Herman, Ralph Branca, Tom Seats, Johnny Peacock, John Dantonio, Clyde King, Eddie Basinski, Art Herring, Curt Davis and Luis Olmo.

The Wabash Limited was a train operated by the Wabash Railroad, a Midwestern rail line popularized by the song, “The Wabash Cannonball.” The train of seven cars and three baggage coaches was listed as passenger train No. 18 on its run from St. Louis to Chicago.

The Dodgers were riding in the rear passenger car. Because of wartime restrictions, sleeper berths were limited, so the Dodgers settled for a day coach. Some of the team members were asleep on the floor of the passenger car when the train approached a diagonal crossing at Route 52, the main business street in the village of Manhattan, about 45 miles southwest of Chicago, at 6:30 a.m. on Sept. 15.

Death on the tracks

A truck, pulling two full gasoline tankers, tried to get through the crossing, but the train hit the rear tanker, causing an explosion, the Decatur (Ill.) Daily Review reported. The locomotive engine became enveloped in fire. Most of the windows on the train were shattered, sending glass flying inside the passenger cars, and flames lapped the open frames.

The train pushed the truck along the track before stopping and the inferno set fire to the office of the nearby Alexander Lumber Company, the Decatur newspaper reported. Two of the lumber company’s warehouses also were destroyed by the blaze, according to the Chicago Tribune.

“Townspeople who saw the collision declared the train was a flaming torch … and the Manhattan fire department had its work cut out for it to keep the flames from destroying the whole of the little town,” The Sporting News reported.

The driver of the train, engineer Charles Tegtmeyer, 69, died instantly of burns while in the cab of the locomotive. Tegtmeyer went to work for the Wabash Railroad as a fireman in 1901 and was promoted to engineer in 1910, the Decatur newspaper reported.

George Ebert, the train’s fireman, who was responsible for maintaining the correct steam pressure in the engine’s boiler, jumped from the locomotive.

Dodgers trainer Harold Wendler “saw the fireman lying outside on the embankment, his blue overalls smoldering,” The Sporting News reported.

According to the Decatur newspaper, Dodgers team members helped Ebert out of his burning clothes.

Wendler administered first aid to Ebert until an ambulance arrived and took him to a hospital about 10 miles away in Joliet, Ill.

The truck driver, Herman Cherry, was picked up along the road and taken to a Joliet hospital by a passing motorist, the Decatur newspaper reported.

Show must go on

According to The Sporting News, Leo Durocher kept the Dodgers calm in the moments immediately following the collision. “Don’t run, fellows,” Durocher said. “Take it easy and go out by the rear door.”

Six passengers on the train were injured slightly by broken glass, the Decatur newspaper reported. According to The Sporting News, Dodgers player Luis Olmo was cut on his right arm by flying glass. Coach Chuck Dressen injured a knee.

The train never left the track, the Decatur newspaper reported. After the fire was extinguished, the entire train was taken to Chicago.

The Dodgers played their game that afternoon and were defeated, 7-6, by the Cubs. Boxscore

Five players who were on the damaged train played in the game: pinch-hitters Babe Herman and Johnny Peacock, and relief pitchers Tom Seats, Clyde King and Cy Buker.

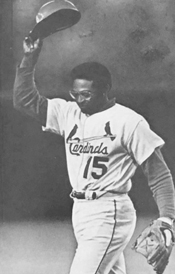

On Sept. 8, 1970, in a game between the Cardinals and Phillies, Allen hit a home run in his final at-bat at Connie Mack Stadium, his baseball home for his first seven seasons in the majors.

On Sept. 8, 1970, in a game between the Cardinals and Phillies, Allen hit a home run in his final at-bat at Connie Mack Stadium, his baseball home for his first seven seasons in the majors. In downtown Cincinnati to promote an Upper Deck Heroes of Baseball old-timer’s game at Riverfront Stadium, Brock met at the Hyatt Regency hotel with my colleague, Geoff Hobson, and me for a wide-ranging interview.

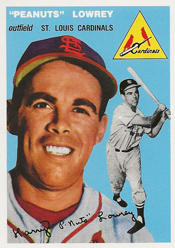

In downtown Cincinnati to promote an Upper Deck Heroes of Baseball old-timer’s game at Riverfront Stadium, Brock met at the Hyatt Regency hotel with my colleague, Geoff Hobson, and me for a wide-ranging interview. What the Cardinals shelled out was peanuts for what they got in return from the pint-sized handyman.

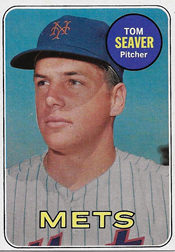

What the Cardinals shelled out was peanuts for what they got in return from the pint-sized handyman. Seaver was the winning pitcher in six of the matchups, Gibson was the winning pitcher three times, and twice their duels ended in no decisions.

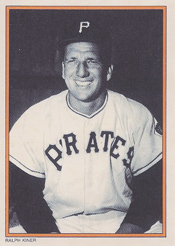

Seaver was the winning pitcher in six of the matchups, Gibson was the winning pitcher three times, and twice their duels ended in no decisions. On Sept. 3, 1950, with the score tied in the bottom of the 10th inning of a game between the Cardinals and Pirates at Pittsburgh, Dyer ordered pitcher Harry Brecheen to give an intentional walk to Kiner with the bases empty and two outs.

On Sept. 3, 1950, with the score tied in the bottom of the 10th inning of a game between the Cardinals and Pirates at Pittsburgh, Dyer ordered pitcher Harry Brecheen to give an intentional walk to Kiner with the bases empty and two outs.