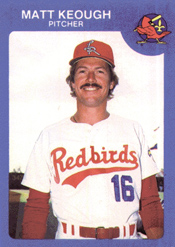

A stint with the Cardinals enabled Matt Keough to share a championship season with his father.

A right-hander who pitched in the majors for nine years, Keough endured an epic losing streak and survived being struck in the temple by a foul ball.

A right-hander who pitched in the majors for nine years, Keough endured an epic losing streak and survived being struck in the temple by a foul ball.

His father, Marty Keough, was a big-league outfielder who became a scout for the Cardinals. Marty scouted for the Cardinals from 1980 to 2018. Matt’s uncle, Joe Keough, also was an outfielder in the majors.

In September 1985, Matt Keough returned to the big leagues with the Cardinals after two seasons in the minors. Matt and Marty were in the same organization for the first time. While Marty was looking for talent to keep the Cardinals successful, Matt was looking to help them win a division title.

Changing positions

Matt Keough was a baseball standout at Corona del Mar High School near Newport Beach, Calif., just as his father Marty was years earlier in Pomona, Calif. A prized prospect of the Red Sox, Marty played 11 years in the majors.

In 1973, Matt, 18, signed with the Athletics after he was chosen in the seventh round of the amateur baseball draft. In his first three seasons (1974-76) in the minors, he played shortstop and third base. His manager in each of those years was Rene Lachemann, a future Cardinals coach.

Lachemann was a Keough booster. Though Keough threw well, he was an inconsistent hitter. When he struggled to hit at spring training in 1977, the Athletics made him a pitcher. “To me, it was make or break,” Keough told The Sporting News.

At Class AA Chattanooga in 1977, Keough led Southern League pitchers in strikeouts (153). He made the jump from Class AA to the majors in September.

Hitting the skids

The next year, Keough was named to the 1978 American League all-star team managed by the Yankees’ Billy Martin. In the All-Star Game at San Diego, Keough relieved Jim Palmer in the third inning and gave up a single to the Cardinals’ Ted Simmons, loading the bases with two outs, before escaping the jam by getting Rick Monday to fly out. Boxscore

A season of promise ended badly when Keough lost his last four decisions and finished at 8-15.

His personal losing streak carried over to the 1979 season. Keough lost his first 14 decisions, giving him 18 consecutive losses over two seasons. His 0-14 record in 1979 tied Joe Harris of the 1906 Red Sox for most losses to start a season. Keough’s 18 consecutive losses were one short of the league record of 19 in a row by Bob Groom of the 1909 Senators and John Nabors of the 1916 Athletics.

The skid ended on Sept. 5, 1979, when Keough got the win against the Brewers at Oakland, pitching a five-hitter before 1,772 spectators, including his uncle Joe. Boxscore

“I’m 1-0 now,” Keough said. “That’s how I’m looking at it. Everything else is behind me.”

Keough finished the 1979 season at 2-17.

Different approach

In the winter after the 1979 season, Keough played in Puerto Rico for a team managed by his former minor-league mentor, Rene Lachemann, who worked to restore the pitcher’s confidence.

Another positive development for Keough was a management change in Oakland. Two years after managing Keough in the All-Star Game, Billy Martin was named Athletics manager in 1980 and his sidekick, Art Fowler, became pitching coach.

“The main thing with Martin and Fowler is the confidence they give you,” Keough told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. “They make you believe.”

According to some American League hitters, including Reggie Jackson and Jim Rice, Martin and Fowler also taught Keough to throw a banned pitch, the spitball.

Keough called the accusations “sour grapes.” Fowler said, “It’s nothing but a little sinker. They just turn the fastball over a little and throw strikes.”

In explaining the pitch to Gannett News Service, Keough said, “Fowler can take you down to that bullpen and show you how to throw the fastball without seams.”

Keough was 16-13, with 20 complete games, for the 1980 Athletics, and the starting staff made the cover of Sports Illustrated the following spring.

Going backward

Keough won his first six decisions of 1981 before feeling pain in his right shoulder. Some suggested Martin overworked him, but Keough said he hurt the shoulder when he slipped on the mound in Baltimore. Keough was 10-6 in 1981 and 11-18 in 1982.

In 1983, Martin returned to New York to manage the Yankees, who made a deal to acquire Keough. Experiencing persistent shoulder pain, Keough was 3-4 with a 5.17 ERA for them.

After the season, Keough agreed to go to the minor leagues in 1984 to try to develop a knuckleball. He was assigned to the Class AA Nashville team because the pitching coach was knuckleball master Hoyt Wilhelm.

After posting a 6.75 ERA in seven starts for Nashville, Keough was diagnosed with a partial tear of the rotator cuff and put on the disabled list. He underwent arthroscopic surgery in October 1984 and the Yankees released him.

Comeback trail

On April 23, 1985, the Cardinals signed Keough to a minor-league contract and sent him to extended spring training in Florida. In 19 innings, Keough had a 1.93 ERA and the Cardinals assigned him to Class AAA Louisville.

Keough, 30, had a 3.35 ERA in 19 starts for Louisville manager Jim Fregosi. “He’s gotten better and better since he’s been with us,” Fregosi told the Louisville Courier-Journal. “I really think he can pitch in the big leagues again.”

Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog said, “He always had a good spitball at Oakland.”

On Sept. 9, 1985, the Cardinals, in first place by a half game ahead of the Mets, called up Keough from Louisville. He made his Cardinals debut that night, pitching four scoreless innings in relief of Kurt Kepshire in a 3-1 win over the Cubs at St. Louis. Boxscore

Five days later, Keough relieved Kepshire again and pitched two scoreless innings against the Cubs in a 5-4 Cardinals win at Chicago. Boxscore

Herzog yanked Kepshire from the rotation and gave Keough a start on Sept. 19 against the Phillies, but he gave up five runs before being lifted in the third inning and the Phillies won, 6-3. Boxscore

“I was pitching 2-and-1 and 2-and-0 on everybody and I usually don’t do that,” Keough told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Keough’s last appearance for the Cardinals came Sept. 24 when he worked two scoreless innings in relief of Ricky Horton in a game the Cardinals won, 5-4, versus the Pirates. Boxscore

Keough was 0-1 with a 4.50 ERA as a Cardinal, but in three relief stints he allowed no runs and struck out eight in eight innings.

Checkered past

The 1985 Cardinals went on to win the National League pennant. Keough was ineligible to pitch in the postseason because he joined the club too late, but the Cardinals gave him a championship ring. Granted free agency, he signed with the Cubs and split the 1986 season, his last in the majors, with them and the Astros.

Keough made one appearance against the Cardinals. Filling in for scheduled starter Dennis Eckersley, who developed back spasms, Keough pitched four innings, gave up a two-run single to Ozzie Smith and took the loss in a 4-3 Cardinals win over the Cubs at St. Louis on June 5, 1986. Boxscore

Like his father Marty, who finished his playing career in Japan in 1968, Matt went to Japan and pitched for four years (1987-90) with the Hanshin Tigers.

Keough, who had a big-league career record of 58-84, tried a comeback with the Angels at spring training in 1992. While seated in the dugout during a game at Scottsdale, Ariz., Keough was hit in the temple by a foul ball off the bat of the Giants’ John Patterson. Marty Keough, scouting the game for the Cardinals, watched as medical personnel attended to his son. Matt developed a blood clot in his brain and needed surgery.

Keough recovered and went on to scout for the Angels and Rays. He also served as special assistant to the general manager of the Athletics.

In April 2005, Keough was involved in a car accident in California, injuring a pedestrian. He pleaded guilty to felony charges of driving under the influence after he crashed his vehicle into another at a red light, pushing the vehicle into a man walking his bike across the street, police said to the Orange County Register. The injured man was admitted to a hospital.

In December 2007, Keough was arraigned on charges he was binge drinking at a bar in violation of his probation, authorities told the Orange County Register. The arrest came less than a week after Keough was released from the Newport Beach lockup, where he spent seven weeks as a jail trustee washing patrol cars and cleaning the facility after he was caught violating parole.

Hacker managed teams in the St. Louis farm system for four years and was a big-league coach on Herzog’s staff for five seasons, including 1987 when the Cardinals were National League champions. Hacker also was a coach for the Blue Jays when they won consecutive World Series titles in 1992 and 1993.

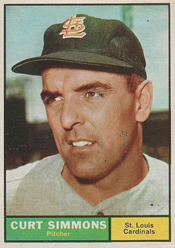

Hacker managed teams in the St. Louis farm system for four years and was a big-league coach on Herzog’s staff for five seasons, including 1987 when the Cardinals were National League champions. Hacker also was a coach for the Blue Jays when they won consecutive World Series titles in 1992 and 1993. On May 19, 1960, the Cardinals signed Simmons on his 31st birthday. A left-handed pitcher, Simmons was released a week earlier by the Phillies after he played in 13 seasons for them and won 115 games.

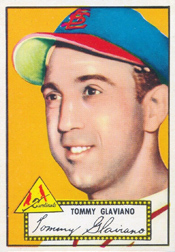

On May 19, 1960, the Cardinals signed Simmons on his 31st birthday. A left-handed pitcher, Simmons was released a week earlier by the Phillies after he played in 13 seasons for them and won 115 games. On May 18, 1950, Glaviano made four errors, including three in a row in the ninth inning, in a game against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. The Cardinals, who led 8-0 entering the eighth inning, lost 9-8.

On May 18, 1950, Glaviano made four errors, including three in a row in the ninth inning, in a game against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. The Cardinals, who led 8-0 entering the eighth inning, lost 9-8. Johnny Lindell faced the Cardinals in a World Series as a Yankees outfielder and in a regular season as a pitcher for the Pirates and Phillies. He also played for the Cardinals for a couple of months when they sought power for their lineup.

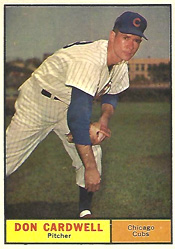

Johnny Lindell faced the Cardinals in a World Series as a Yankees outfielder and in a regular season as a pitcher for the Pirates and Phillies. He also played for the Cardinals for a couple of months when they sought power for their lineup. On May 15, 1960, Cardwell pitched a no-hitter for the Cubs against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field in Chicago. It was Cardwell’s first appearance for the Cubs since being acquired from the Phillies, and it was the first no-hitter pitched against the Cardinals in 41 years. Before Cardwell, Hod Eller of the Reds was the last to do it on May 11, 1919.

On May 15, 1960, Cardwell pitched a no-hitter for the Cubs against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field in Chicago. It was Cardwell’s first appearance for the Cubs since being acquired from the Phillies, and it was the first no-hitter pitched against the Cardinals in 41 years. Before Cardwell, Hod Eller of the Reds was the last to do it on May 11, 1919.