(Updated Nov. 25, 2024)

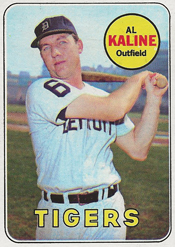

In a World Series filled with epic performances and major controversies, Al Kaline produced with his usual quiet consistency. His steady professionalism calmed the Tigers and inspired them to overtake the defending champion Cardinals.

The Hall of Fame right fielder played in the major leagues for 22 years, all with the Tigers, and appeared in one World Series, the 1968 classic.

The Hall of Fame right fielder played in the major leagues for 22 years, all with the Tigers, and appeared in one World Series, the 1968 classic.

After the Cardinals won three of the first four games, the Tigers rallied to win the last three, including Games 6 and 7 at St. Louis. The 1968 World Series was highlighted by:

_ The Cardinals’ Bob Gibson striking out 17 batters in Game 1.

_ The Tigers’ Mickey Lolich overshadowing teammate and 30-game winner Denny McLain by earning three wins, including Game 7.

_ Cardinals catalyst Lou Brock trying to score standing rather than sliding and being called out, turning the tide in the pivotal Game 5.

_ Gold Glove center fielder Curt Flood failing to catch a drive by Jim Northrup, allowing the Tigers to take control in Game 7.

Kaline, who got into the World Series lineup as the right fielder because of Tigers manager Mayo Smith’s bold decision to shift Mickey Stanley to shortstop, didn’t do anything epic or controversial, but his performance was integral.

Kaline batted .379 against the Cardinals and had an on-base percentage of .400. He had 11 hits, two home runs and eight RBI. He also fielded splendidly.

After the Tigers’ Game 7 triumph, Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “You know what the turning point in the Series was? It was Kaline carrying them all along with him. That’s what beat us.”

Rising up

Kaline was born in Baltimore and grew up in a row house. His father worked in a broom factory and his mother scrubbed floors. His parents encouraged Kaline to play baseball.

“My dad was always there to play catch with me,” Kaline told Joe Falls of The Sporting News. “He’d be on his feet all day long at the factory and he’d come home dead tired, but we’d go down to the corner and start playing catch. He’d hit me some fly balls.”

In a 1965 profile, Sports Illustrated reported, “The Kaline family was poor, proud and hungry _ no Kaline had ever graduated from high school _ and before long the whole clan had decided little Al was going to be something different.”

Like his contemporary, Mickey Mantle, Kaline had osteomyelitis, a bone infection. “When he was 8 years old, doctors took two inches of bone out of his left foot, leaving jagged scars and permanent deformity,” Sports Illustrated reported. “They left him with a set of sharply swept-back toes on his left foot. Only two of those toes touch the ground when he walks, which has forced him to develop a running style on the heel and toes of his right foot and on the side of his left foot.”

Kaline overcame his physical limitations and developed into a top prospect. On June 19, 1953, Kaline, 18, signed with the Tigers for $30,000.

“He turned every penny of it over to his father and his mother,” Sports Illustrated reported. “The mortgage was paid off on the house and Mrs. Kaline’s failing eyesight was saved by an operation.”

On June 25, 1953, a week after his signing, Kaline made his debut in the majors against the Athletics at Philadelphia and never played a day in the minors.

Under pressure

In 1955, Kaline, 20, became the American League batting champion, hitting .340. He had 200 hits and struck out a mere 57 times.

Asked who Kaline reminded him of, Red Sox slugger Ted Williams replied, “Joe DiMaggio,” The Sporting News reported.

Kaline was called the Tigers’ best player since Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer and comparisons also were made to Ty Cobb. For Kaline, it was too much too soon.

“The worst thing that happened to me in the big leagues was the start I had,” Kaline said. “This put the pressure on me. Everybody said this guy’s another Ty Cobb, another Joe DiMaggio. What they didn’t know is I’m not that good a hitter. I have to work as hard, if not harder, than anybody in the league.”

Described by Bob Broeg of the Post-Dispatch as “gracefully methodical,” Kaline remained the Tigers’ best player, even though he suffered setbacks such as a fractured cheekbone, fractured collarbone, rib injuries and a broken right hand.

According to Broeg, Chuck Dressen, who managed Kaline from 1963-66 after managing the Reds, Dodgers, Senators and Braves, said, “He’s the best player who ever played for me. Jackie Robinson was the most exciting runner I ever had and Hank Aaron the best hitter, but for all around ability _ hitting, fielding, running and throwing _ I’ll go with Al.”

On May 25, 1968, Kaline’s right forearm was broken when hit by a pitch from Lew Krausse of the Athletics. Mayo Smith moved Jim Northrup from center to right and put backup Mickey Stanley in center.

The outfield of Stanley, Northrup and Willie Horton in left excelled, and when Kaline returned to the lineup on July 1 he split time with Northrup in right and with Norm Cash at first base.

After the Tigers clinched the pennant, Smith moved Stanley to shortstop, a position he hadn’t played, for nine games in place of weak-hitting Ray Oyler. Satisfied Stanley could handle the switch, Smith kept Stanley at shortstop for the World Series and went with an outfield of Horton, Northrup and Kaline.

New heights

The Cardinals in 1968 were in the World Series for the third time in five years. The Tigers hadn’t been in a World Series since 1945. Kaline had waited 16 seasons for the chance. Entering Game 1 at St. Louis, “I’d never been so nervous in my life, ” Kaline told The Sporting News.

Kaline hit a double against Gibson but also struck out three times. Gibson tied Sandy Koufax’s World Series strikeout mark of 15 when he fanned Kaline for the first out in ninth before completing the game with strikeouts of Cash and Horton.

Said Kaline: “That was the greatest pitching I’ve seen in a long, long time.” Boxscore

(In 2018, Kaline told Joe Schuster of Cardinals Yearbook that Gibson “will always go down in my mind as the best pitcher I ever faced _ by far.”)

In Game 2, Kaline had two hits and scored two runs, but his defense was the story. In the first inning, the Cardinals had Julian Javier on second and Flood on first with one out when Orlando Cepeda lifted a ball to the corner in right. As the ball sliced into foul territory, Kaline, stationed in right-center, raced over, made a running one-handed catch and crashed through a gate.

“I guess I was only about a step, or a step and a half, away from the sideline fence out there,” Kaline told the Post-Dispatch. “I figured I’d make the catch, stop, pivot and throw, but when I hit the fence, I went through it. It’s well-padded out there, but there’s a gate, and I hit it. I was surprised when the fence opened.”

Kaline’s throw to the infield kept both runners from advancing.

The next batter, Mike Shannon, hit a looping fly to right-center and Kaline made another running one-handed grab. Boxscore

In Game 3 at Detroit, Kaline hit his first World Series home run, a two-run shot versus Ray Washburn. Boxscore In Game 4, Kaline had two of the Tigers’ five hits versus Gibson, but the Cardinals were a win away from clinching the championship. Boxscore

Title run

In the seventh inning of Game 5, the Cardinals led, 3-2, but the Tigers loaded the bases with one out. Kaline came up to face Joe Hoerner, a left-handed reliever. “The situation called for a right-handed replacement,” the Post-Dispatch declared, “but Schoendienst’s lack of regard for his right-handed relievers seemed even more pronounced than his confidence in Hoerner.”

Kaline took a mighty cut at a Hoerner pitch and missed. “He was trying for the home run with the bases loaded,” said Mayo Smith, “but then he realized he had to get the base hit.”

Kaline stroked Hoerner’s next pitch to right-center for a two-run single, giving the Tigers a 4-3 lead on the way to a 5-3 victory. Boxscore

“I wanted to hit it up the middle to get away from the double play,” said Kaline. “I enjoy batting with men on base. When there aren’t, there’s no incentive.”

The Series returned to St. Louis and the Tigers cruised to a 13-1 victory in Game 6. Kaline contributed three hits, four RBI and three runs. In the Tigers’ 10-run third inning, Kaline had two hits, a RBI-single against Washburn and a two-run single versus Ron Willis. In the fifth, he hit a solo home run off Steve Carlton. Boxscore

“I wanted it to go seven games,” Kaline said. “If we lose it, I want it to be to Gibson.”

Gibson and Lolich were locked in a scoreless duel in Game 7 until the Tigers broke through with three runs in the seventh and went on to a 4-1 victory. Boxscore

Cardinals general manager Bing Devine showed his respect by going into the Tigers’ clubhouse to congratulate Kaline and shake his hand.

For the Series, Kaline hit .571 with runners in scoring position. He was 4-for-5 versus Cardinals left-handers.

In the Post-Dispatch, Bob Broeg wrote, “It’s nice that this underrated athlete has made the most of the long-awaited Series opportunity, even if it has come at the expense of the Cards.”

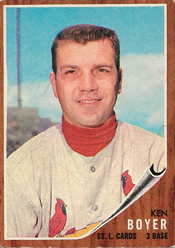

The unusual feat occurred in the second inning of a game against the Dodgers at St. Louis.

The unusual feat occurred in the second inning of a game against the Dodgers at St. Louis. The Hall of Fame right fielder played in the major leagues for 22 years, all with the Tigers, and appeared in one World Series, the 1968 classic.

The Hall of Fame right fielder played in the major leagues for 22 years, all with the Tigers, and appeared in one World Series, the 1968 classic. On April 18, 1950, the Cardinals became the first major-league team to play a season opener at night. Club owner Fred Saigh said he opted for an Opening Night game because it gave more working people a chance to attend.

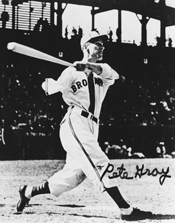

On April 18, 1950, the Cardinals became the first major-league team to play a season opener at night. Club owner Fred Saigh said he opted for an Opening Night game because it gave more working people a chance to attend. On April 17, 1945, Gray made his debut in the big leagues as the left fielder in the season opener for the defending American League champion Browns at St. Louis.

On April 17, 1945, Gray made his debut in the big leagues as the left fielder in the season opener for the defending American League champion Browns at St. Louis. On April 15, 1970, Torrez pitched a one-hitter for the Cardinals against the Expos at St. Louis. The win was the 11th in a row for Torrez. He won his last nine decisions of 1969 for the Cardinals and his first two of 1970.

On April 15, 1970, Torrez pitched a one-hitter for the Cardinals against the Expos at St. Louis. The win was the 11th in a row for Torrez. He won his last nine decisions of 1969 for the Cardinals and his first two of 1970. A 6-foot-3, 250-pound right-hander whom The Sporting News described as a “hurling Hercules,” Lee had the most intimidating fastball in the American League when he was a closer for the Angels in the 1960s.

A 6-foot-3, 250-pound right-hander whom The Sporting News described as a “hurling Hercules,” Lee had the most intimidating fastball in the American League when he was a closer for the Angels in the 1960s.