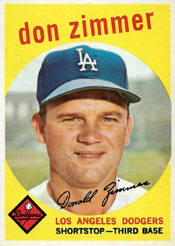

The Cardinals tried to acquire Don Zimmer to be their second baseman but were outmaneuvered by the Cubs.

On April 8, 1960, the Dodgers told Zimmer he would be traded later in the day to either the Cardinals or the Cubs. Zimmer said he preferred to go to the Cubs because they would play him at third base, his favorite position.

On April 8, 1960, the Dodgers told Zimmer he would be traded later in the day to either the Cardinals or the Cubs. Zimmer said he preferred to go to the Cubs because they would play him at third base, his favorite position.

The Cardinals offered the Dodgers a pair of minor-league players and cash. The Cubs offered three minor-leaguers and cash.

After weighing both offers, the Dodgers chose the Cubs, dealing Zimmer for pitcher Ron Perranoski, infielder John Goryl and outfielder Lee Handley. Only Goryl had big-league experience, but Perranoski was the prize. The left-hander became a prominent reliever for the Dodgers.

The Cardinals’ failure to land Zimmer turned out to be fortuitous. A month later, they made a trade with the Pirates for Julian Javier, who developed into an all-star and was their second baseman on three National League championship clubs.

Hard knocks

In December 1959, the Cardinals traded second baseman Don Blasingame to the Giants for shortstop Daryl Spencer and outfielder Leon Wagner. With the acquisition of Spencer, the Cardinals planned to shift Alex Grammas from shortstop to second base.

Near the end of spring training in 1960, when the Dodgers started shopping Zimmer, the Cardinals saw an opportunity to upgrade at second base. Zimmer (29) was five years younger than Grammas (34). The Cardinals thought it would be better to have Grammas in a utility role.

Zimmer was available because Maury Wills had taken over the Dodgers’ shortstop job and Bob Lillis was a capable backup.

In 1953, Zimmer was beaned in a minor-league game, suffered a skull fracture and needed a plate inserted in his head. He made his debut in the majors with the Dodgers in 1954 and two years later suffered a broken cheekbone when beaned again by a pitch from Hal Jeffcoat of the Reds.

Zimmer “just doesn’t get out of the way,” pitcher Sal Maglie said to the Associated Press.

After being used primarily as a backup at second, third and short, Zimmer became the Dodgers’ starting shortstop in 1958 and hit .262 with 17 home runs.

“A colorful fielder, Zimmer looks like a chubby Nellie Fox, always yelling encouragement about the infield with a wad of chewing tobacco bulging in his jaw,” the Associated Press observed.

Zimmer returned as Dodgers shortstop in 1959, but struggled to hit for average. “Likable little Zimmer never has ceased stubbornly to swing for the fences,” Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted.

In June 1959, the Dodgers called up Wills from the minors and the speedster supplanted Zimmer, who never got untracked and finished the season with a .165 batting mark for the National League champions.

Time to go

At spring training in 1960, Zimmer choked up on the bat and shortened his swing. “I’ve never seen Zimmer look better,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston told The Sporting News.

Alston may have been trying to prop up Zimmer’s trade value. He and Zimmer weren’t getting along.

“I wanted to get away, especially from Alston,” Zimmer told the Associated Press. “I know he doesn’t care for me. That’s because I’m always after him to play me or trade me.”

The Cardinals and Cubs were the most ardent suitors for Zimmer. The Cubs wanted him as the third baseman to replace Alvin Dark, who they traded to the Phillies in January 1960.

According to the Chicago Tribune, Zimmer “stated frankly he was not interested in going to the Cardinals when he learned they planned to play him at second base. He prefers third.”

The Dodgers “were understood to be seeking a suitable place for Zimmer in the major leagues,” the Tribune reported, “and his preference for the Cubs undoubtedly was taken into consideration.”

The Cardinals offered two minor-league players and cash to the Dodgers for Zimmer, the Post-Dispatch reported, adding the identities of the players were unknown. It’s possible pitcher Jim Donohue and outfielder Duke Carmel were the minor-leaguers offered because two months later the Cardinals dealt them to the Dodgers for outfielder John Glenn.

According to the Associated Press, Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi told Zimmer, “You’re going to either the Cubs or the St. Louis Cardinals. I can’t tell you yet. I’ll be able to tell you later on.”

A few hours later, Zimmer learned he was a Cub.

“I would have liked to have had Zim because he can play three infield positions well and I like his fire,” Cardinals manager Solly Hemus told the Post-Dispatch.

Foiled in their attempt to acquire Zimmer, the Cardinals turned their attention to a Pirates prospect, Julian Javier, whose path to the majors was blocked by Bill Mazeroski, a future Hall of Famer. On May 28, 1960, the Cardinals dealt pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell and infielder Dick Gray to the Pirates for reliever Ed Bauta and Javier, who became their mainstay at second base for more than a decade.

Crowd pleaser

Zimmer was the third baseman when the Cubs opened the season on April 12, 1960, against the Dodgers at Los Angeles. In his first at-bat as a Cub, Zimmer hit a home run against his former teammate, Don Drysdale.

“The crowd of 67,550 stood and cheered Don as he rounded the bases,” The Sporting News reported.

Zimmer told the Los Angeles Times, “I can’t think of anything that has happened to me in baseball that gave me a bigger thrill, and I hit it off one of my best buddies.” Boxscore

The next day, Zimmer was chatting with Drysdale at the ballpark when Dodgers outfielder Duke Snider approached and informed them his wife stood and applauded for Zimmer when he hit the home run.

Zimmer replied, “I can top that one. I saw Ginger Drysdale outside the dressing room after the game and she gave me a kiss and a hug.”

In June 1960, the Cubs called up prospect Ron Santo from the minors, put him at third base and moved Zimmer to second. Zimmer eventually played for the Mets, Reds, Dodgers again, and Senators before ending his playing career in 1965.

From 1971 through 2006, Zimmer was in the major leagues as either a coach or manager. He had a 906-873 record as manager of the Padres, Red Sox, Rangers, Cubs and Yankees.

On April 8, 1970, the Cardinals sent Montanez to the Phillies as partial compensation for Curt Flood’s failure to report after being traded.

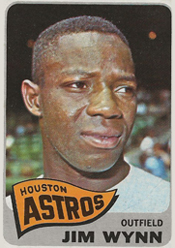

On April 8, 1970, the Cardinals sent Montanez to the Phillies as partial compensation for Curt Flood’s failure to report after being traded. Beginning with the Houston Colt .45s and continuing with their renamed version, the Astros, Wynn launched long balls wherever he played.

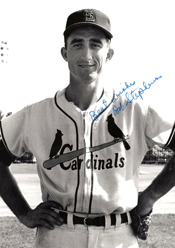

Beginning with the Houston Colt .45s and continuing with their renamed version, the Astros, Wynn launched long balls wherever he played. Rising to the challenge, Stephenson hit and fielded consistently well in his short stint as a starter flanked by star-studded teammates.

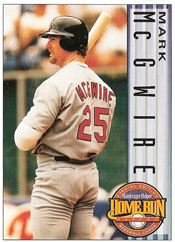

Rising to the challenge, Stephenson hit and fielded consistently well in his short stint as a starter flanked by star-studded teammates. In March 2000, the Cardinals could have faced the Mets in the first major-league regular-season game played outside North America, but they rejected the opportunity after their star attraction, McGwire, opposed the plan.

In March 2000, the Cardinals could have faced the Mets in the first major-league regular-season game played outside North America, but they rejected the opportunity after their star attraction, McGwire, opposed the plan. On March 31, 1970, the Cardinals released Hernandez, a left-handed reliever who was on their roster in spring training. The Cardinals came to regret the move.

On March 31, 1970, the Cardinals released Hernandez, a left-handed reliever who was on their roster in spring training. The Cardinals came to regret the move.