(Updated March 14, 2024)

Jim Leyland needed a break from managing, but he wasn’t done with baseball.

On Nov. 30, 1999, the Cardinals hired Leyland to be a special assignment scout.

The move came two years after Leyland managed the 1997 Marlins to a World Series championship and two months after he managed the Rockies to a last-place finish.

The move came two years after Leyland managed the 1997 Marlins to a World Series championship and two months after he managed the Rockies to a last-place finish.

In leaving the Rockies with two years remaining on his contract, Leyland said he wanted more time with family and was done managing.

Who you know

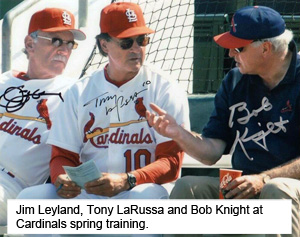

Leyland began managing in the Tigers’ farm system in 1972 when he was 27. In 1979, Leyland was managing Evansville of the American Association when he and rival manager Tony La Russa of the White Sox’s Iowa farm team developed a mutual respect.

“He was impressive to manage against,” La Russa said in a 2024 article for Memories and Dreams magazine. “He was very creative on offense, his team played hard and he really had a feel for pitching. He looked like he was going to be an outstanding coach and manager in the major leagues if given the opportunity.”

In August 1979, La Russa became White Sox manager. Leyland was stuck in Evansville because the Tigers were content with their manager, Sparky Anderson. After the 1981 season, Leyland became a coach on La Russa’s White Sox staff. They bonded with a young White Sox executive, Dave Dombrowski.

“With his expertise in all phases of the game, Jim was immediately embraced by the players as somebody who would contribute to the chemistry you need on a winning team,” La Russa said in Memories and Dreams magazine.

The Pirates hired Leyland in 1986. He managed them for 11 seasons and won three division titles before Dombrowski, who’d become general manager of the Marlins, lured him to Miami. In 1997, Leyland’s first season as their manager, the Marlins won the World Series championship, a stunning feat for a franchise which entered the National League just four years earlier. The joy quickly faded when Marlins owner Wayne Huizenga ordered player payroll slashed. With the roster depleted, the Marlins were 54-108 in 1998 and Leyland wanted out.

Burned out

Leyland became Rockies manager but it wasn’t a good fit. The 1999 Rockies finished 72-90 and Leyland grew disinterested. He missed his wife and two children, who were home in suburban Pittsburgh, and after 14 consecutive seasons as a big-league manager he’d had enough. Leyland told the Rockies he was retiring from managing and would forfeit the $4 million left on his contract.

Years later, he told the Associated Press he walked out because “it would’ve been more of a disaster and morally wrong to go back and take their money for two more years.”

Leyland said he did “a lousy job” with the Rockies. “I stunk because I was burned out,” he said. “When I left there, I sincerely believed I would not manage again.”

In Memories and Dreams magazine, La Russa said, “He left Colorado when he didn’t think he was making a difference. He walked away from money. That’s integrity.”

Leyland signed with the Cardinals two weeks before he turned 55. The arrangement called for him to scout National League teams in Pittsburgh and American League clubs in Cleveland. Leyland also would attend Cardinals spring training and evaluate players.

Though Leyland reported directly to general manager Walt Jocketty, he also had the support of La Russa, who said he was comfortable having his friend in the organization. “I’m not going to be the manager of the Cardinals,” Leyland said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He knows that. I know that.”

Baseball whisperer

When Leyland attended his first Cardinals spring training in 2000, the club wanted to issue him a uniform with No. 10, the same number worn by La Russa and the number Leyland wore when he managed. La Russa said he was OK with it, but Leyland declined, the Post-Dispatch reported.

“I thought it would have made a joke out of it,” said Leyland. “It would have called too much attention and it wasn’t necessary to draw that kind of attention.”

Leyland requested and got a uniform with no name or number.

In September 2000, when the Cardinals were nearing a return to the postseason for the first time in four years, La Russa was asked how much Leyland had helped. “He set the tempo in spring training (with) evaluations and suggestions about strategy,” La Russa replied.

Leyland spent six seasons (2000-2005) as Cardinals special assignment scout and they got to the postseason in five of those. During spring trainings, La Russa and Leyland sat together at games. Leyland also managed or coached intra-squad and “B” games on the back fields at the Jupiter, Fla., complex.

“Jim Leyland is the best baseball man I’ve ever been around in my life,” La Russa said in April 2005. “He’s got this special feel for the game and that includes his giving you his honest evaluation.”

In Memories and Dreams magazine, La Russa said Leyland became “re-energized” working for the Cardinals. “He really helped us, and evidently we helped him,” said La Russa.

In October 2005, Dombrowski, who’d become Tigers general manager, fired manager Alan Trammell and hired Leyland to replace him. Getting the chance to return to the organization where he started was one reason Leyland accepted the job. Another is he felt haunted by the way he left the Rockies. “I did not want my managerial career to end like that,” Leyland said.

In a storybook twist, Leyland, 61, led the Tigers to the American League pennant in 2006 and a World Series matchup with La Russa’s Cardinals.

“It’s actually the greatest situation you could imagine _ to be in a situation against somebody you respect so much,” La Russa said.

Years later, in Memories and Dreams magazine, La Russa had a different perspective. He said, “When you manage against a friend, it’s a very difficult thing because, at the end of the day, one of us will be happy and the other will be upset. You don’t want to see your friend upset. The best example of that was in the 2006 World Series when Jim was with Detroit. That wasn’t fun.”

The Cardinals won four of five against the Tigers and became World Series champions for the first time in 24 years.

Leyland managed the Tigers for nine seasons and won another pennant in 2012. He came close to having a World Series rematch with La Russa and the Cardinals in 2011, but the Tigers were ousted by the Rangers in the American League Championship Series.

On Nov. 28, 1989, Smith, a free agent, signed a three-year $6 million contract with the Cardinals.

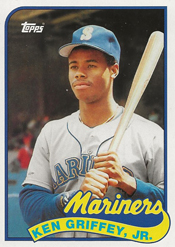

On Nov. 28, 1989, Smith, a free agent, signed a three-year $6 million contract with the Cardinals. Griffey, a center fielder who won 10 Gold Glove awards and four times led the American League in home runs with the Mariners, was eligible to become a free agent in another year.

Griffey, a center fielder who won 10 Gold Glove awards and four times led the American League in home runs with the Mariners, was eligible to become a free agent in another year. Noren was an outfielder for 11 seasons in the major leagues, including five (1952-56) with the Yankees and three (1957-59) with the Cardinals.

Noren was an outfielder for 11 seasons in the major leagues, including five (1952-56) with the Yankees and three (1957-59) with the Cardinals. On Nov. 21, 1969, the Cardinals dealt right fielder

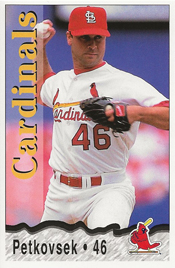

On Nov. 21, 1969, the Cardinals dealt right fielder  Petkovsek signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Nov. 18, 1994, his 29th birthday. Projected to spend 1995 with the Louisville farm club, Petkovsek was called up to the Cardinals when injuries depleted their pitching staff.

Petkovsek signed a minor-league contract with the Cardinals on Nov. 18, 1994, his 29th birthday. Projected to spend 1995 with the Louisville farm club, Petkovsek was called up to the Cardinals when injuries depleted their pitching staff.