(Updated Aug. 8, 2025)

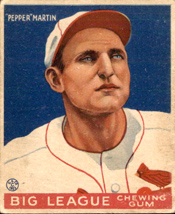

Pepper Martin interrupted a successful stint as a manager to return to the Cardinals as a player and help them get to another World Series.

In 1943, Martin managed in the Cardinals’ farm system for the third consecutive year. After the season, while in St. Louis to interview for a radio sports announcer job, Martin met with Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, who was looking for players to replace those called to serve in the military during World War II.

In 1943, Martin managed in the Cardinals’ farm system for the third consecutive year. After the season, while in St. Louis to interview for a radio sports announcer job, Martin met with Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, who was looking for players to replace those called to serve in the military during World War II.

Accepting Breadon’s offer to come back to the Cardinals, Martin, 40, was a utility player for them in 1944 and contributed to a successful run to a third consecutive National League pennant.

With mission accomplished, Martin sought to resume his managing career and the Cardinals obliged by giving him his unconditional release in October 1944.

Spice to the lineup

When Martin was an infant in Temple, Oklahoma, he’d nap on a sack in the cotton fields while his family harvested the crop, according to Wilbur Adams of the Sacramento Bee. Martin was 6 when the family moved to Oklahoma City.

“Ever since I was old enough to handle a baseball, I loved the game,” Martin recalled in a column for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

When Martin was 9, he worked a newspaper route in Oklahoma City. “I’d get up at 3:30 every morning to get the Daily Oklahoman to the homes of my readers,” Martin said to the St. Louis Star and Times, “but before I delivered a single paper I used to sit down under a street corner lamp and study the box scores of the major leagues. In winter, I’d read the gossip of the hot stove league.”

Martin told the Inquirer, “The Red Sox were going great in those days and they were my favorite team. I had a pretty good memory as a kid and I knew by heart the averages of pretty nearly every big leaguer. I saved enough out of my earnings as a newsboy to buy my first glove and I had it stuck in my back pocket wherever I went and whatever I did. Not so many kids in my neighborhood had gloves, and owning that mitt gave me almost as much happiness as would a couple of home runs in a World Series game.”

While playing for a minor-league team in Texas when he was 21, Martin was signed by Cardinals scout Charley Barrett.

Martin debuted with the Cardinals in 1928. With his aggressive, fun-loving style of play, he was a prominent part of the Cardinals clubs of the 1930s. Martin and his pal, pitcher Dizzy Dean, symbolized the spirit of the group known as the Gashouse Gang. Dean “was just a big-hearted old country boy, from a cotton patch, like myself,” Martin said to The Sporting News. “So I guess that’s why I liked old Diz.”

An outfielder and third baseman nicknamed “Wild Horse of the Osage,” Martin led the National League in stolen bases three times and scored more than 120 runs in a season three times.

As a third baseman, Martin “introduced a style of play all his own,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. Martin described his approach to fielding groundballs as “stop it with your chest, then throw them out.”

In the 1931 World Series against the Athletics, Martin had an on-base percentage of .538, producing 12 hits and two walks in 26 plate appearances, and swiped five bases. He batted .355 and scored eight runs in the 1934 World Series versus the Tigers. “Pepper always was fighting to win, trying for that extra base or an impossible chance, no matter whether his team was miles ahead or furlongs behind,” The Sporting News noted in an editorial.

After the 1940 season, Martin became a player-manager in the Cardinals’ farm system. His Sacramento teams finished 102-75 in 1941 and 105-73 in 1942.

In 1943, Martin took over a Rochester team which finished 59-93 the year before and helped it improve to 74-78. One of his best Rochester players was shortstop Red Schoendienst.

Martin batted .280 for Rochester and “was the best outfielder on the club,” Sam Breadon said. “He could outrun any man on the club on the bases.”

Slow to age

Martin told the Associated Press he was offered a radio sports broadcasting job for 1944 but after talking with Breadon decided to play instead.

Breadon told the Post-Dispatch, “I asked him how he would like to play with the Cardinals and he shot back, ‘I sure would.’ ”

Though he was 40, Martin insisted his age was 10 because his birthday was Feb. 29, a date which appears on the calendar only once every four years.

“He still has his old-time sparkle and speed,” said Cardinals manager Billy Southworth. “I think he will help a lot.”

Said Martin: “I’ll play any time and place they need me.”

Teaching by example

Martin played in 40 games, 29 as an outfielder, for the 1944 Cardinals, and had an on-base percentage of .386. He finished with a flourish, producing five hits, including a home run, in the last eight at-bats of his big-league career.

He also was a mentor who “sold the Cardinals’ rookies on his undying spirit,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

After the Cardinals won the 1944 Word Series championship against the Browns, Martin asked for his release so he could “negotiate for any coaching or managerial post he wants,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

Breadon mailed him the release on Oct. 13, 1944, and Martin received it on Oct. 16. “We hate to let him go, but he wants it that way,” Breadon said.

San Diego, an unaffiliated minor-league team in the Pacific Coast League, needed a manager and identified two finalists, Martin and Casey Stengel. Martin got the job and Stengel went to manage the Yankees’ farm club at Kansas City.

Martin managed 14 seasons in the minors and had an overall record of 1,083-910.

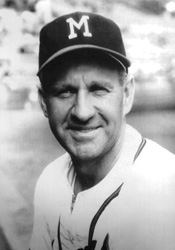

Slaughter, who began his big-league career with the Cardinals in 1938 and became one of their all-time best, played his last game in the majors for the Braves in 1959.

Slaughter, who began his big-league career with the Cardinals in 1938 and became one of their all-time best, played his last game in the majors for the Braves in 1959. On Oct. 9, 1969, Caray, the voice of the Cardinals for 25 years, was fired by the sponsor of the broadcasts, Anheuser-Busch.

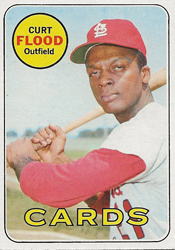

On Oct. 9, 1969, Caray, the voice of the Cardinals for 25 years, was fired by the sponsor of the broadcasts, Anheuser-Busch. In October 1969, the Cardinals dealt Flood, catcher Tim McCarver, pitcher

In October 1969, the Cardinals dealt Flood, catcher Tim McCarver, pitcher  On Oct. 4, 1944, Denny Galehouse outdueled Cardinals ace Mort Cooper and George McQuinn hit a two-run home run in the Browns’ 2-1 victory in Game 1 of the World Series at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis.

On Oct. 4, 1944, Denny Galehouse outdueled Cardinals ace Mort Cooper and George McQuinn hit a two-run home run in the Browns’ 2-1 victory in Game 1 of the World Series at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. On Oct. 1, 1944, Laabs hit a pair of two-run home runs, powering the St. Louis Browns to a 5-2 victory over the Yankees and clinching the club’s lone American League championship.

On Oct. 1, 1944, Laabs hit a pair of two-run home runs, powering the St. Louis Browns to a 5-2 victory over the Yankees and clinching the club’s lone American League championship.