To get batters out in the big leagues, Randy Jones needed to make them hit the ball on the ground.

That’s what the Padres left-hander did when he pitched his most impressive game _ a 10-inning one-hitter to beat the Cardinals in 1975. Twenty-two of the 30 outs were ground balls.

When batters lifted the ball in the air against Jones, bad stuff often happened _ like the game at St. Louis when Hector Cruz and Lou Brock hit inside-the-park home runs to beat him in 1976.

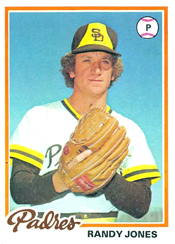

A 20-game winner the season after he lost 22, and recipient of the 1976 National League Cy Young Award, Jones was 75 when he died on Nov. 18, 2025.

Portrait of a prospect

Randy Jones grew up in Brea, Calif., near Anaheim. Another prominent big-league pitcher, Walter Johnson, spent his teen years there after his family moved from Kansas. Looking to cash in on an oil boom, the Johnsons settled in the village of Olinda, now a Brea neighborhood.

Jones liked baseball and followed the Dodgers (his favorite players were Sandy Koufax and Tommy Davis). He showed promise as a pitcher. In 1963, when Jones was 13, his school principal asked a friend, Washington Senators left-hander Claude Osteen, to give the teen a pitching lesson. Osteen emphasized to Jones the importance of throwing strikes and keeping the ball down in the zone.

“He had a good sinker, even at 13,” Osteen recalled to The Sporting News, “but he threw sidearm. I advised him to throw more overhanded, or three-quarters.”

Jones went on to pitch in high school and at Chapman College, but arm ailments caused him to lose velocity. In explaining why he’d offered Jones only a partial baseball scholarship in 1968, University of Southern California (USC) coach Rod Dedeaux told columnist Jim Murray, “He’s only got half a fastball.”

Padres scouts Marty Keough and Cliff Ditto saw enough to recommend Jones. The Padres picked him in the fifth round of the 1972 amateur draft. Keough (who later scouted for the Cardinals) told Dave Anderson of the New York Times, “He threw strikes … and he got people out.”

Welcome to The Show

Duke Snider and Jackie Brandt, the former Cardinal, were Jones’ managers in the minors, but the person who had the biggest influence on him there was pitching instructor Warren Hacker. A former Cub and the uncle of future Cardinals coach Rich Hacker, Warren Hacker “taught me to throw a better sinker,” Jones told the New York Times. “He showed me how to place my fingers differently and how to apply pressure with them.”

The sinker became the pitch that got Jones to the big leagues just a year after he was drafted. His debut with the Padres came in June 1973 versus the Mets. The first batter to get a hit against Jones was 42-year-old Willie Mays, who blasted his 656th career home run over the wall in left-center at Shea Stadium. Boxscore

A week later, Jones made his first start, at home versus the Braves, and Hank Aaron, 39, became the second player to slug a homer against him. It was the 692nd of Aaron’s career. “The home run came off a fastball outside,” Aaron told United Press International. “The kid got it up. Had it been down a little, I probably would have popped it up.” Boxscore

Facing Aaron and Mays, who were big-leaguers before Jones started kindergarten, wasn’t the end of the rookie’s storybook experiences. His first big-league win came in the ballpark, Dodger Stadium, where Jones’ father took him as a youth to cheer for the home team. Jones beat them, pitching a four-hitter and getting 18 outs on ground balls. Dazed, he told The Sporting News, “I finished the ninth inning and didn’t realize the game was over.” Boxscore

Reconstruction project

Based on Jones’ seven wins as a rookie, including a shutout of the 1973 Mets (who were on their way to becoming National League champions), the Padres had high hopes for him in 1974, but Jones instead posted an 8-22 record. Though the Padres scored two or fewer runs in 17 of those losses, lack of support wasn’t the sole reason for the poor mark. Jones’ pitching deteriorated as the season progressed (4.46 ERA in August; 6.23 in September.) “My confidence was completely shot,” he told The Sporting News.

After the season, the Padres hired pitching coach Tom Morgan. As Angels pitching coach, Morgan turned Nolan Ryan into an ace by getting him to alter his shoulder motion. “If you ask me who had more influence on me than anybody in my career, I’d have to say Tom Morgan,” Ryan told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Morgan did for Jones what he’d done for Ryan. “He said I was opening up too soon with my right shoulder, that I wasn’t pushing off the rubber with my left foot, that I was pitching stiff-legged and that I was throwing all arm and no body,” Jones said to The Sporting News.

In short, Jones told the Los Angeles Times, Morgan “basically reconstructed my delivery … He gave me the fundamentals to be consistent.”

The turnaround was immediate. Jones was 20-12 with a league-best 2.24 ERA in 1975. He won two one-hitters _ versus the Cardinals and Reds.

Luis Melendez (who batted .248 for his career, but .571 against Jones) singled sharply to open the seventh for the lone St. Louis hit. The Cardinals managed just two fly balls. “It was the best game of my career because of all the ground balls the Cardinals hit,” Jones told the Associated Press. Boxscore

Two months later, facing a lineup featuring Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez, Jones gave up only a double to Bill Plummer and beat a Big Red Machine team headed for a World Series championship. He got 20 outs on ground balls. Boxscore

After Jones induced 22 ground-ball outs in a three-hit shutout of the Braves, pitcher Phil Niekro said to The Sporting News, “You get the feeling he can make the batter ground the ball to shortstop almost any time he wants to.” Boxscore

Location and movement

Jones basically relied on a sinker and slider. Roger Craig, who became Jones’ pitching coach (1976-77) and then manager (1978-79), said Jones threw a sinker 60 to 70 percent of the time, and a slider the other 30 to 40 percent. “Craig estimates that Jones’ sinker breaks down five to 10 inches and breaks away up to six inches from a right-handed batter,” the New York Times reported.

Jones’ fastball was clocked at about 75 mph. Foes and teammates alike kidded him that it was more like 27 mph.

In rating pitchers for the Philadelphia Daily News, Pete Rose said “the two who gave me the most trouble were Jim Brewer and Randy Jones.”

Rose was a career .183 hitter versus Jones. “Randy had him crazy,” Padres catcher Fred Kendall told the New York Times. Kendall recalled when Rose stood at the plate and yelled to Jones, “Throw hard, damn it, throw hard.”

Cardinals first baseman Ron Fairly told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1975, “He has a sinker. That’s all it is, and not a very hard one at that.”

Fairly’s teammate, Keith Hernandez, saw it differently. In his book “I’m Keith Hernandez,” the 1979 National League batting champion said of Jones, “Anyone who dismissed him as a soft tosser missed the point. With a hard sinker and a wicked hard slider, much like Tommy John’s, Randy threw his fastball hard enough to keep hitters off-balance.”

As Jones told The Sporting News, “My fastball is good enough that I can come inside on right-handed hitters and keep them honest.”

Jones also put batters out of synch by working fast. A game with Jones and Jim Kaat as starting pitchers was completed in one hour, 29 minutes. Jones finished a two-hitter versus Larry Dierker and the Astros in one hour, 37 minutes. Boxscore and Boxscore

Six of Jones’ 1975 wins came in games lasting less than one hour, 45 minutes.

Ups and downs

Jones followed his 20-win season of 1975 with a league-leading 22 wins and the Cy Young Award in 1976. He also was first in the league in innings pitched (315.1) and complete games (25), and had a stretch of 68 innings without issuing a walk.

Though the Cardinals were a mess (72-90) that season, they played like the Gashouse Gang when facing Jones. He was 1-3 against them.

On June 18, 1976, the Cardinals snapped Jones’ seven-game winning streak with a 7-4 victory at Busch Memorial Stadium.

In the fourth inning, with Ted Simmons on second, Hector Cruz (hitless against Jones in his career) drove a high pitch deep to left-center. Willie Davis leapt and got his glove on the ball, but, when he hit the wall, the ball popped free and shot toward the infield. Cruz circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

An inning later, with Don Kessinger on first, Lou Brock (a career .190 hitter versus Jones) punched a pitch to right-center. The ball hit a seam in the AstroTurf, bounced over Davis’ head and rolled to the wall. Brock streaked home with the second inside-the-park homer of the game. “The odds are real strong on that not happening again,” Jones told the Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

In October 1976, Jones had surgery to repair a severed nerve in the bicep tendon of his left arm. He never had another winning season, finishing with a career mark of 100-123.

Terrific tutor

Back home in Poway, Calif., Jones placed an ad in a local newspaper, offering private pitching instruction. Joe Zito signed up his son, 12-year-old Barry Zito, at a cost of $50 per lesson. “We had it,” Joe Zito recalled to the New York Times. “It was the food money.”

The lessons took place in the backyard of Jones’ hilltop home. Getting pitching tips from a Cy Young Award winner was something “I would kind of marvel at,” Barry Zito told the Associated Press.

According to the New York Times, Jones tutored Zito, a left-hander, once a week for more than three years and videotaped their sessions. Jones used a tough-love approach. One time, after Zito kept throwing pitches into the middle of the strike zone, Jones yelled, “We’re not playing darts. Never throw at the bull’s-eye.”

Zito recalled to the Associated Press, “When I did something incorrectly, he’d spit tobacco juice on my shoes, Nike high-tops we could barely afford.”

Reminded of that, Jones told the wire service, “I had to get his attention, and that worked with Barry. He didn’t focus really well when we first started. By the time, he got into his teens, he locked in. He just kept getting better.”

In 2002, two years after reaching the majors with Oakland, Zito was a 23-game winner and recipient of the American League Cy Young Award.

I love the way his career began, serving up those homeruns to maybe two of the greatest players of all-time – Mays and Aaron and then winning his first game at Dodgers Stadium, same place dad took him to see his first game. Musta had Jones shaking his head, the way a scientist might stand at the church altar and surrender. But seriously, I enjoyed this post and remember the 77 Jones card with All star written across the bottom and his Gamble-like afro and some slight resemblance to Gene Wilder in Willy Wonka.

Pitching coaches like Tom Morgan are so underrated and how tremendous for Jons to pass on his pitching wisdom. I appreciate when baseball player and people identify and express gratitude to those who have had an impact on them and having said that I think of you as a sort of pitching coach Mark, always providing profound isights and encouragement and I thank you for that.

I enjoyed your comments, Steve. In 1978, Randy Jones and Oscar Gamble were Padres teammates. Perhaps they shared hair-styling tips. You’re right about the Randy Jones resemblance to Gene Wilder.

I’m glad you appreciated the part about Willie Mays and Hank Aaron being the first two to hit home runs against Jones. Eddie Mathews was manager of those 1973 Braves, and, after seeing Jones for the first time, Mathews told United Press International, “He doesn’t throw the ball hard but he has a lot of poise. When hitters come back to the dugout talking to themselves, you know the guy can pitch.”

The player who hit the most career home runs versus Jones was Johnny Bench, with seven. On May 29, 1980, at San Diego, Bench slugged three homers in a game against Jones.

The Gamble hair connection. I love it, only fashion, but the scarier a pitcher looks, I would think the more effective he is or maybe not. Greg Maddux could pass as a choir boy, but then again so could Vincente Padilla.

I have a soft spot for soft throwing, crafty left handers like Brent Suter and now Randy Jones.

Oscar Gamble started displaying an Afro when he was with Cleveland. In 2006, he told Matt Michael of the Syracuse Post-Standard, “I would wear it during the offseason, and then I’d get it cut, but I wasn’t getting much playing time, so I started wearing the Afro to try to get the manager’s attention to get in the lineup.” Asked whether that worked, Gamble replied, “I think so, but some people think the reason I wasn’t playing was because I had the Afro.”

When he was with the Yankees, club owner George Steinbrenner ordered Gamble to ditch the Afro. He had it cut during spring training at Fort Lauderdale. It took the barber an hour to do the job. “They carted the hair away in bushel baskets,” Yankees coach Elston Howard told Bob Hertzel of the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Those Gamble hairs should be in the hall of fame! Not a bad career either…200 homers and a .356 OB% though he drove in 666 runs which I think symbolizes choosing the beast over god. I’m not into religion anymore, but some of its stories are entertaining.

Thanks Mark for writing a piece on Randy Jones. He’s certainly worthy of it. After all these years Randy Jones has the second most victories for a Padres pitcher. And still holds the top spot for appearances, innings pitched, complete games and shutouts. That’s pretty good for a pitcher who didn’t have “anything”. He was a breath of fresh air when he first came up and was always fun to watch. Apparently though, the fast pace that Randy Jones worked off the mound didn’t sit well with the San Diego Chicken who back then was paid by the hour! I was wondering Mark how today’s swing for the fences hitters would fare against a healthy Randy Jones. I was also wondering Mark could it be that he came back too soon after having surgery? Once again thanks for another great read.

It’s impressive that Randy Jones still is high on the list of Padres career pitching leaders in so many categories. Thanks for the info, Phillip.

Regarding your question of how Jones would do against today’s swing-from-the-heels batters, Jones may have provided the answer when he told columnist Jim Murray in 1975, “I prefer big, free-swinging teams like Pittsburgh. My fastball sinks, and when they jump on it, they beat it into the ground. The batters, who, like me, deal in the corners, give me the most trouble.”

Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell told the Los Angeles Times, “When Jones is in his groove, there isn’t much you can do with the strikes he throws.”

Jones perhaps did come back too soon from October 1976 arm surgery. It sure didn’t help that Padres manager John McNamara started Jones in the 1977 season opener at Cincinnati. The groundskeepers plowed chunks of snow off the field before the game. The day was raw and frigid, with a temperature of 37 degrees and 15 mph winds. Jones pitched five innings, gave up five runs, lacked command and told Bill Ford of the Cincinnati Enquirer, “I must have made 150 pitches.”

After lasting just two innings in a June 17, 1977, start versus the Cardinals, Jones went on the disabled list. Padres team physician Dr. Paul Bauer told the Associated Press, “I don’t see any point in letting him pitch again this season.” Jones, however, was back on the mound for the Padres on July 31.

In pretty much every sport I appreciate technical skill more than brute force. A pitcher with a 75 mph fastball certainly fits that category. That also means you don’t have to go to the bullpen after five innings. And about that no-hitter… What do you think the statistical probability is that you can induce 22 ground balls in a game and not have a single one find a hole?

What a great question – “probability that you can induce 22 ground balls in a game and not have a single one find a hole?”

When Randy Jones was at his best, his games were a day off for his outfielders.

Jones, too, was an adept fielder. In 1976, his Cy Young Award season, he fielded 112 chances without an error.

I love the tobacco juice on the sneakers! Quite the story that both teacher and student both won the CY. Zito was dominant that year but was seemingly never the same after that.

I was hoping you would enjoy the Barry Zito part of the post, Gary. In the stories I read in researching, it seems Zito had a genuine fondness for his time with Randy Jones.

One of the anecdotes Zito told the Associated Press involved Jones encouraging the youngster to practice his windup indoors in front of a mirror, using a rolled up sock as a ball. “He would always tell me, ‘You have to do 500,000 windups. Get the damn sock, throw it in front of the mirror and get the mechanics down.’ ” Zito recalled.

In addition to pitching mechanics and pitch location and movement, Zito said Jones also taught him “the mental side, never giving up.”

I recall Pete having trouble getting the bat on the ball with this guy. Randy Jones was so underrated. He was also one player whose baseball card always seemed to find its way into my new packs lol. Great story about his tutoring of Zito, and it tracks he had to get Zito to dial in. It also tracks Randy liked to face the big swingers. He had the arsenal to deal with ’em. Great post, Mark.

Thanks, Bruce. A couple of follow-ups of note on what Pete Rose told the Philadelphia Daily News in 1981: After citing Jim Brewer and Randy Jones as the pitchers who gave him the most trouble, Rose was asked to name the best overall pitcher he’d ever faced. He picked Juan Marichal because of his ability to throw 4 or 5 pitches effectively. Rose also named Bob Gibson and Jim Bunning as the most competitive pitchers he’d faced and Sandy Koufax as the hardest thrower.

Mike Schmidt was one of the batters who gave Randy Jones the most trouble. Schmidt produced 26 career hits (including six home runs) and 14 walks versus Jones. That gave Schmidt a career .446 on-base percentage and .338 batting average against the left-hander.

I’m not sure Randy Jones and his 75 mph fastball would even get a look today. He had four seasons with >250 innings pitched, including 315+ with 25 complete games in his Cy Young season. While he didn’t throw hard, he wasn’t immune to arm trouble. Those sharp breaking sinkers are tough on the elbow. I enjoyed reading about players I usually associate with other teams–Willie Davis with the Padres and Don Kessinger and Ron Fairly with the Cardinals.

I enjoyed your astute comments about Randy Jones and I share your appreciation for finding familiar players on unfamiliar teams. Though good players and good hitters, Willie Davis and Don Kessinger couldn’t solve Randy Jones. Davis for his career was 3 for 16 (.188) against Jones; Kessinger was 5 for 29 (.172).

Another great and fun write up. A couple of things. First, he is the answer to a trivia question: name the only Cy Young Award winner with a career losing record.

Second, I remember when he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1976 and the title was something like “Threat to win 30 games?” In early August he was involved in a car accident and while he was pitching fairly quickly again, he went 4-8 the rest of the season. The Padre run support was terrible but he also didn’t seem to quite have the same stuff. Then on the last game of the season he injured his elbow and was never quite the same thereafter. But he was a master pitcher in 1975-1976.

I loved the statements in the article that he threw strikes and got people out. Whatever happened to that being valuable in today’s game? It’s strikeouts or bust and not every pitcher has the physical tools to throw heat consistently.

Thom A

I appreciate all of your keen insights, Thom. It’s enlightening to look back at a time when a magazine such as Sports Illustrated highlighted and respected a pitcher who had a chance to win 30 in a season. I prefer that to today’s nonsensical “conventional wisdom” that wins don’t matter as much as WAR, WAA and WHIP.

I didn’t realize Randy Jones is the only CY Young Award winner with a career losing record. His 22-14 mark in 1976 was certainly Cy Young worthy _ unlike the records of recent Cy Young Award winners such as Jacob deGrom (10-9 in 2018 and 11-8 in 2019) and Paul Skenes (10-10 in 2025) and others.

I get the modern metrics and I’ve come to appreciate them as well as how well Skenes and deGrom pitched when they won. But the point is to win the game and I miss pitchers who knew they “didn’t have their stuff” that day, but labored 8-9 innings to protect 5-4 or even 7-5 leads, etc.

Also, I loved the insights on how Willie Mays and Hank Aaron hit the first 2 homers off of Jones in his career, along with Luis Melendez batting .571 against Jones, while Pete Rose hit .183! Crazy stuff indeed.

Thom A.

I like how you expressed your thoughts about metrics and wins.

One more crazy stat stuff: Randy Jones’ final start in the big leagues came against the Cardinals on Aug. 10, 1982, at Shea Stadium. He faced six batters and retired just one (George Hendrick on a sacrifice fly). In three starts against the 1982 Cardinals, Jones was 0-2 with an 11.42 ERA: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1982/B08100NYN1982.htm