A right-handed pitcher and protege of Cardinals ace Harry Brecheen, Jerry Walker became the right-hand man to Cardinals general manager Walt Jocketty.

Walker was involved with professional baseball most of his adult life. At 18, he went from high school to the majors with the Orioles and was nurtured by Brecheen, the pitching coach who’d been a World Series standout with the 1946 Cardinals.

Walker was involved with professional baseball most of his adult life. At 18, he went from high school to the majors with the Orioles and was nurtured by Brecheen, the pitching coach who’d been a World Series standout with the 1946 Cardinals.

At 20, Walker became the youngest pitcher to start in an All-Star Game. He played eight seasons in the American League with the Orioles (1957-60), Athletics (1961-62) and Indians (1963-64).

After his playing days, Walker managed in the minors, then returned to the big leagues as a scout and went on to become a coach and general manager. For 13 years (1995-2007), he was an executive in the Cardinals’ front office, advising Jocketty on player personnel.

Mighty leap

Born and raised in Ada, Okla., Walker was a high school baseball phenom, posting a varsity pitching record of 52-1 and leading his club to state titles in 1956 and 1957. He hit .529 as a junior and .526 his senior season.

Most big-league teams tried to sign him, including the Red Sox, who projected Walker as a third baseman, but he chose the Orioles, in large part, because of Brecheen, an Ada resident. “Brecheen had a great deal to do with Walker’s decision,” the Baltimore Sun noted.

Brecheen told the newspaper, “I’ve known the boy and his family for a long time … I thought when I saw him in high school that he had the best curve of any kid I’d ever seen.”

After signing with the Orioles on June 28, 1957, Walker joined a pitching staff with the likes of former Negro League fastballer Connie Johnson, World War II combat veteran Hal Brown and ex-Dodgers standout Billy Loes.

A week later, Walker made a jittery big-league debut at Boston’s Fenway Park. With the Red Sox ahead, 6-2, Orioles manager Paul Richards sent Walker to pitch the seventh. He issued walks to the first two batters _ two-time American League batting champion Mickey Vernon and Jackie Jensen (past and future AL RBI leader) _ and went to a 2-and-0 count on Frank Malzone before being relieved by Art Ceccarelli, a winless left-hander. Malzone mashed a pitch that soared over the the head of right fielder Tito Francona for a triple. Boxscore

After three relief appearances, Walker made his first start, facing the hapless Athletics at Kansas City. Nervous and overanxious, he didn’t last an inning. Boxscore

Breakout game

A month later, after a few relief stints, none longer than two innings, Walker got his second start, this time at home, against the Senators. Though destined to finish in the basement, the Senators had Roy Sievers, the slugger from St. Louis who would lead the American League in home runs (42) and RBI (114) that year.

Pitching with the poise and stamina, Walker shut out the Senators for 10 innings and got the win, 1-0. He allowed four singles and a walk, totaling 111 pitches.

“Here is a kid who had never pitched nine innings in his life,” Paul Richards said to the Baltimore Sun. “The high schools where Jerry played limit their games to seven innings.”

Brecheen told the newspaper, “We knew he had a lot of ability, and he’s got a lot of heart.”

Walker dressed quickly after the game and dashed out of the clubhouse. As the Sun explained, “With a pocketful of hot change, the quiet-spoken, crew-cut kid was busting out all over in his (eagerness) to reach the nearest coin telephone to place a long-distance call to (his parents in) Oklahoma.” Boxscore

Seeing stars

After a tune-up season in the minors at Knoxville (18-4, 2.61 ERA) in 1958, Walker was one of three 20-year-old pitchers (Jack Fisher and Milt Pappas being the others) who contributed to the Orioles in 1959.

Walker sizzled early, winning his first four decisions, including a five-hitter against the Yankees. He struck out Mickey Mantle three times. Boxscore

In a rematch in July, Walker again beat the Yankees, fanning Mantle three more times and totaling 10 strikeouts for the game. “For 20 years old, you’d have to say the young man was amazing the way he struck my men out,” Yankees manager Casey Stengel said to the Sun. Boxscore

(Though he whiffed 12 times versus Walker in his career, Mantle had an on-base percentage of .500 _ 13 hits and 11 walks _ against him and slugged four home runs. Of Walker’s four career wins versus the Yankees, three came in 1959.)

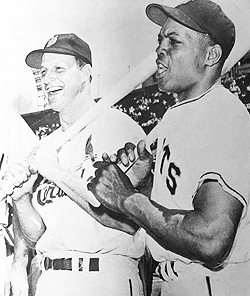

A month later, Stengel, the American League manager, chose Walker to start in the All-Star Game at Los Angeles. Walker got the win, allowing one run in three innings. He twice retired the Cardinals’ Ken Boyer, struck out Eddie Mathews and got Willie Mays and Ernie Banks to ground out. Boxscore

Working overtime

On Sept. 11, 1959, the first-place White Sox, headed for an American League pennant, were at Baltimore for a Friday doubleheader on Westinghouse Night. As the Sun noted, “The air was electric with tension.”

Jack Fisher shut out the White Sox in the opener, 3-0, limiting them to three hits. Boxscore

Walker started Game 2 against a lineup headed by future Hall of Famers Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox. He gave up two singles in the first but the White Sox never advanced another runner as far as third the rest of the night.

White Sox pitchers Barry Latman (9.1 innings) and Gerry Staley, the ex-Cardinal, were superb, too, but Walker was better. He pitched 16 scoreless innings and the Orioles prevailed, 1-0, when Brooks Robinson’s two-out single versus Staley, 39, drove in Al Pilarcik from third.

“That two 20-year-olds should pitch 25 scoreless innings in one night against the league leaders, even the light-hitting White Sox, borders on the unbelievable,” wrote Ed Brandt of the Sun.

His colleague, Lou Hatter, offered, “Walker’s performance was extra-special, incredible and then some.”

Walker told United Press International, “I could have pitched another couple of innings.” Boxscore

He finished the year 11-10 with a 2.92 ERA, but never had another winning season in the majors.

On the move

In 1960, Walker suffered from allergies “that sapped his strength,” the Sun reported, and posted a 3-4 season record. “From what they told me, I guess I was allergic to just about everything,” Walker told the Kansas City Times. “They gave me some shots and also some pills to take regularly. The shots are a long-range treatment and the doctors seem to think they should clear up the trouble completely in two or three years.”

Traded to the Athletics in April 1961, he spent two years with them, went 16-23 and got dealt again, to Cleveland, where he played his final two seasons in the majors. A highlight came on July 13, 1963, when Walker pitched four scoreless innings of relief, helping Cleveland teammate Early Wynn, 43, get career win No. 300. Boxscore

In May 1964, Walker was loaned by Cleveland to the Cardinals’ Class AAA farm club, the Jacksonville Suns, managed by Harry Walker (no relation). His teammates included pitchers Mike Cuellar, Bob Humphreys, Gordon Richardson and Barney Schultz, who went on to help the Cardinals win a pennant and World Series championship that season.

Walker was 10-9 with Jacksonville, including a one-hitter in a 1-0 victory versus Richmond in 10 innings. Called up to Cleveland in September, he pitched his final big-league games that month.

Still in the game

Walker was a manager in the Yankees’ farm system for six seasons (1968-73) and his pitchers included a pair of future American League Cy Young Award winners _ Ron Guidry and LaMarr Hoyt. Walker was a Yankees scout from 1974 to 1981, then became their pitching coach for parts of the 1981 and 1982 seasons.

From 1983-85, Walker was Astros pitching coach. His staff ace was Nolan Ryan.

After a stint from 1986-91 as special assignment scout for the Tigers, Walker was promoted to general manager by club president Bo Schembechler and tasked with rebuilding the roster. As Gene Guidi of the Detroit Free Press noted, “Walker stepped into a tough spot in Detroit. He wants to make the Tigers a better team but he has few marketable players to trade and a limited spending budget to pursue free agents.”

In Walker’s first season as general manager, the Tigers were 75-87. They improved to 85-77 in 1993, but the franchise underwent an ownership change, and Walker was fired in January 1994.

Cardinals influencer

In November 1994, Walt Jocketty, who replaced Dal Maxvill as Cardinals general manager, hired Walker to be the club’s director of major league player personnel. “He was the first guy I hired in St. Louis,” Jocketty told the Cincinnati Enquirer.

“Walker’s duties will feature special assignment scouting and recommendations to Jocketty,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Three years later, in February 1997, Walker was promoted, with the title of vice president of player personnel. The Post-Dispatch referred to him as Jocketty’s “right-hand man.”

According to the Cardinals 1997 media guide, Walker “assists Jocketty in personnel matters with the major league club and he is also responsible for overseeing the Cardinals player development and scouting activities.”

One of the up-and-coming Cardinals staffers in 1997 was a scouting assistant, John Mozeliak. According to the Post-Dispatch, Walker was a mentor to Mozeliak.

During Walker’s 13 years with the Cardinals, they won two National League pennants (2004 and 2006) and a World Series title (2006).

In October 2007, Jocketty was fired and replaced by Mozeliak. “One of Walt’s strong points was how he used his people,” Walker told the Post-Dispatch. “He allowed Mo (Mozeliak) to be involved, to increase his responsibilities.”

When the Reds then hired Jocketty to be team president and general manager, he brought in Walker to serve as his special assistant for player personnel.

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported. In two June relief appearances Dean made for the 1934 Cardinals, National League president John Heydler credited him with wins in both, even though other pitchers appeared to qualify instead.

In two June relief appearances Dean made for the 1934 Cardinals, National League president John Heydler credited him with wins in both, even though other pitchers appeared to qualify instead. In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years.

In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years. After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.

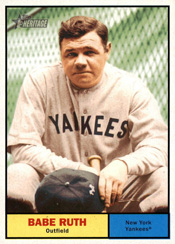

After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.