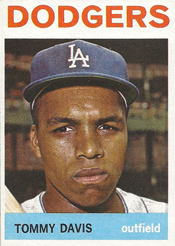

Tommy Davis twice hit home runs to beat Bob Gibson in 1-0 shutouts pitched by Sandy Koufax.

A two-time National League batting champion who totaled 2,121 hits, Davis batted .167 versus Gibson, but made a lasting impression on the Cardinals’ ace with those game-winning homers.

A two-time National League batting champion who totaled 2,121 hits, Davis batted .167 versus Gibson, but made a lasting impression on the Cardinals’ ace with those game-winning homers.

In his autobiography, Gibson said, “The man on the Dodgers who could beat you, whom you couldn’t let beat you, was Tommy Davis.”

Local guy

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Davis excelled in multiple sports at Boys High School. His basketball teammate was Lenny Wilkens, who launched a Hall of Fame playing career with the St. Louis Hawks.

A right-handed hitter, Davis was a prized baseball prospect. The Phillies and Yankees wanted him, but he chose the Dodgers in 1956 after Jackie Robinson phoned him and made a pitch, according to the Society for American Baseball Research.

The Dodgers departed Brooklyn for Los Angeles after the 1957 season, and Davis made his big-league debut two years later in a game at St. Louis against the Cardinals. Boxscore

In 1960, the Cardinals also were the opponent when Davis got his first big-league hit (against Ron Kline) and his first big-league home run (against Bob Duliba).

Civil rights

in 1961, the Dodgers’ spring training site, Holman Stadium in Vero Beach, Fla., still had segregated seating and segregated bathrooms. According to author Jane Leavy in the book “Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy,” Davis led a contingent of Dodgers players to see Peter O’Malley, who was in charge of the facility, and said to him, “We got to change this.”

O’Malley agreed, but at the ballpark the next day the black fans, unconvinced they could sit where they wanted, were in what had been the segregated section near the right field corner. According to Leavy, Davis and his teammates “took them by the hand and led them out of the stands” and showed them it was all right to sit anywhere. “Directing traffic until they got used to it,” Davis said.

Smart hitter

A couple of months later, on May 25, 1961, 6,878 spectators attended a Thursday night matchup between Koufax and Gibson at St. Louis.

Davis, starting at third base and batting fifth, struck out his first two times at the plate. In “Stranger to the Game,” Gibson said, “I had been striking him out with sliders low and away, and I seemed to have the edge on him.”

Gibson was on a roll, having retired seven consecutive batters, when Davis led off in the seventh inning.

“I had noticed that, as I continued to pitch him outside, Davis was gradually sneaking up toward the plate,” Gibson said. “He was practically on top of the plate, and so, out of duty, I buzzed him inside with a fastball.

“I don’t know if he was setting me up, but he must have been looking for the fastball on his ribs, because he backed off a step, turned on that thing, and crushed it over the left field fence.”

In the book “Sixty Feet, Six Inches,” Gibson said, “I think he was just waiting for me to bring one inside, and I was still young and dumb enough to oblige him.”

Cardinals catcher Hal Smith told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “The pitch Davis hit wasn’t even a strike.”

The home run into the bleacher seats in left-center broke a streak of 20 consecutive scoreless innings for Gibson and was all Koufax needed. He pitched a three-hit shutout for a 1-0 victory. It was the first time Koufax pitched a complete game against the Cardinals. Boxscore

Dodgers pitching coach Joe Becker told the Post-Dispatch, “Finally, after six years of trying, he’s putting all of his baseball abilities together.”

Brooklyn brotherhood

A year later, on June 18, 1962, Gibson and Koufax engaged in another duel before 33,477 attendees on a Monday night at Dodger Stadium.

Through eight innings, the Dodgers’ only hits were two singles by ex-Cardinal Wally Moon. Koufax limited the Cardinals to five singles.

The game was scoreless when Davis batted in the bottom of the ninth with one out and none on.

“Smart guy that I am, I remembered that Davis had beaten me the year before when I stopped pitching him outside and came in with a fastball,” Gibson said in “Stranger to the Game.”

“I thought, ‘Now, he remembers that I remember that pitch inside, and so he’s thinking that there’s no way I’m coming inside again in this situation. Just to cross him up, I’m going to do it again.’

“So, I threw the fastball inside again, and goddamn if he didn’t hit it out again to beat me. I learned right then that the dumbest thing you can do as a pitcher is try to be too smart.”

With the count 1-and-0, Davis told the Post-Dispatch, he was looking for a fastball. “Gibson had been getting me out on breaking stuff,” Davis said. “He was throwing the fastball when he got behind.”

Davis’ walkoff home run deep into the bullpen in left gave Koufax and the Dodgers another 1-0 victory. It was the first time Koufax pitched a complete game without allowing a walk. Boxscore

“There are instances, as Tommy Davis taught me twice over, when a pitcher can think too much,” Gibson said in “Stranger to the Game.” “That was a hard lesson for me.”

In “Sixty Feet, Six Inches,” Gibson said, “It was a textbook case of overthinking. Dumb, dumb, dumb. Worse yet, I went against my better judgment. When I started winning big was when I stopped doing stuff like that.”

After the game, according to Jane Leavy, Davis and his wife went to a Los Angeles nightspot and saw Gibson there.

“I walked over to him and he said, ‘Hi, how you doing, Tom?’ ” Davis told Leavy. “My wife says, ‘Oh, is this the guy you hit the home run off?’ I’m thinking, ‘I’m dead. I’m dead. I’m dead.’ “

Hit man

In September 1963, the Dodgers were a game ahead of the second-place Cardinals entering a series at St. Louis. After the Dodgers won the first two games, Gibson started the finale.

With the Cardinals ahead, 5-1, Davis faced Gibson with the bases loaded in the eighth inning and delivered a two-run single, knocking Gibson from the game. The Dodgers rallied and prevailed in 13 innings, sweeping the series on their way to winning the National League pennant. Boxscore

Davis had an amazing season in 1962, leading the National League in batting (.346), hits (230) and RBI (153). Those were the most hits by a National League player since Stan Musial had 230 for the 1948 Cardinals, and the most RBI by a National League player since Joe Medwick had 154 for the 1937 Cardinals.

Davis repeated as National League batting champion in 1963, hitting .326.

In May 1965, Davis broke his right ankle and he wasn’t the same ballplayer after that. Coveted as a designated hitter in the American League in the 1970s, he played 18 seasons in the majors and hit .294.

Stargell struck out swinging in seven consecutive plate appearances versus the Cardinals in September 1964.

Stargell struck out swinging in seven consecutive plate appearances versus the Cardinals in September 1964. On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash.

On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash. With the designated hitter being used in the National League for the first time in 2022, it may be a while before the Cardinals pick a pitcher to be a pinch-hitter. Even if a pitcher was needed to bat, the odds would be against him getting a hit after a long layoff as a batter.

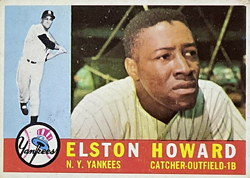

With the designated hitter being used in the National League for the first time in 2022, it may be a while before the Cardinals pick a pitcher to be a pinch-hitter. Even if a pitcher was needed to bat, the odds would be against him getting a hit after a long layoff as a batter. It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try.

It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try. On March 26, 1952, the Cardinals claimed Mauch for $10,000 after he was placed on waivers by the Yankees.

On March 26, 1952, the Cardinals claimed Mauch for $10,000 after he was placed on waivers by the Yankees.