While pitching in the Cardinals’ organization, Pete Mazar became known as much for his vocal cords as for his arm.

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.

An urban melting pot across the Hudson River from Manhattan, Hoboken in Sinatra’s time was known for its gritty industrial docks and was the setting for the film “On the Waterfront.” In contrast, the borough of High Bridge has a reputation as a place for parks, trails and scenic beauty. A resident, Howard Menger, wrote “The High Bridge Incident,” a book about his claim of having met space aliens in the woods near High Bridge when he was a boy. Otherworldly, indeed.

Little lefty

Pete Mazar had eight brothers (including a twin) and five sisters, according to The Sporting News. Though no more than 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds, he was a standout athlete in soccer, basketball and baseball at High Bridge High School.

After graduation in June 1940, Mazar was a machinist for the local Taylor-Wharton Iron and Steel Company, makers of railroad fittings and switches and dredging equipment. A left-handed pitcher, he played semipro baseball for the High Bridge team in the well-regarded Tri-County League.

Mazar’s success as a semipro player got him a contract in 1941 with a New York Giants farm club in Milford, Del., but he became ill, pitched briefly and got released, according to the Allentown (Pa.) Morning Call. Returning to High Bridge, Mazar went back to the iron and steel job (the company now was producing material for America’s World War II involvement) and pitched semipro baseball.

In May 1944, with the war depleting baseball team rosters, the Cardinals offered Mazar, 23, a tryout with their Allentown farm club. Allentown manager Ollie Vanek, who had a notable eye for talent (the Cardinals signed 16-year-old Stan Musial on Vanek’s recommendation), took one look at Mazar and gave him a spot on the team. Mazar rewarded him with an 11-6 record.

Promoted by the Cardinals to Columbus (Ohio) in 1945, Mazar pitched a no-hitter against manager Casey Stengel’s Kansas City Blues. Of the 27 outs Mazar recorded using a sharp-breaking curve, 20 came on grounders, the Kansas City Times reported.

American idol

Seven of Mazar’s eight seasons in the Cardinals’ system were spent either with Columbus or Houston. In 1947, he pitched for both. After going 0-4 for Columbus, he was sent to Houston and pitched better for manager Johnny Keane’s club, which was on its way to becoming Texas League champions.

On Aug. 19, 1947, an estimated 13,000 spectators packed into Houston’s Buffalo Stadium for a doubleheader on what was promoted as “appreciation night.” Looking for ways to show their appreciation to fans, club officials gave Mazar a microphone before one of the games and asked him to sing for the crowd. Mazar had “served as a vocalist in a nightclub near his home at High Bridge,” according to The Sporting News.

Crooning hit tunes, Mazar thrilled his audience and was touted as “the Sinatra of baseball,” the Associated Press reported. (Sinatra’s popular songs in 1947 included “Almost Like Being in Love,” “Autumn in New York,” and “Time After Time.”)

Word spread that the Houston club had a silky-voiced troubadour with a smooth delivery. “Now everywhere he goes to play ball, they want him to warble,” according to the Associated Press.

On Aug. 24, it was arranged for Mazar to sing a song before Houston’s game at Dallas. “The crowd of 6,000 roared its approval,” the Associated Press reported. “They called him back for another, and still another. They wanted him for a fourth except that the ballgame had to go on.”

The next night, Aug. 25, Mazar was the starting pitcher for Houston at Oklahoma City. He entertained a crowd of 4,937 with three songs, then got the win against an Oklahoma City club that featured hitters such as Ray Boone and Al Rosen.

Houston club president Allen Russell asked Mazar to spend the winter in Texas so that he could promote his singing.

Fan favorite

Back with Houston and Johnny Keane in 1948, Mazar, 27, had his best season as a pitcher. He won 12 of his first 14 decisions and finished 15-10 with a 2.53 ERA in 228 innings.

His most satisfying win came at home on July 17, 1948. When Houston fans learned Mazar and his wife were expecting their third child, they presented the couple with more than 100 gifts before that night’s game. Mazar thanked the crowd of 7,358, crooned several songs and then pitched a three-hit shutout to beat Tulsa. “I never wanted to win a game so much in my life … I didn’t want to let all of those good people down,” Mazar told The Sporting News.

Mazar’s successful 1948 season didn’t do enough to impress the Cardinals. When they didn’t put him on their 40-man winter roster, the Cubs claimed him in the November 1948 minor-league draft on the recommendation of scout Jigger Statz. Mazar reminded him of Tony Freitas, another pint-sized left-hander who pitched in the majors during the 1930s, Statz told the Los Angeles Times.

Assigned to the Cubs’ Los Angeles Angels farm team in 1949, Mazar was 2-4 for the Pacific Coast League team when he got sent back to Houston in May.

In April 1950, Mazar was struck by a line drive, breaking his left thumb. It didn’t hurt his singing, but it did his pitching. The 1951 season was Mazar’s last in the Cardinals’ system. He pitched three more years in the minors but never reached the big leagues _ either as a player or a singer.

Returning to High Bridge, Mazar and his wife operated a tavern and he also worked as a machinist for F.L. Smidth & Company, makers of equipment for mining and cement industries.

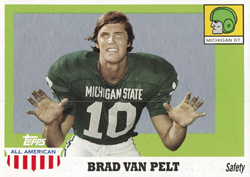

Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport.

Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf.

In 1958, his first season with the Cardinals, Flood, 20, clouted 10 homers. Those are the most home runs of any Cardinals player 20 or younger, according to researcher Tom Orf. A few days before the June 2000 baseball draft, the Reds brought Molina, 17, from his home in Puerto Rico to work out with other potential picks at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium.

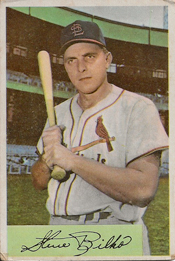

A few days before the June 2000 baseball draft, the Reds brought Molina, 17, from his home in Puerto Rico to work out with other potential picks at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. From the moment the Cardinals signed him, in 1945, Bilko intrigued with his power. He was big _ 6-foot-1 and, as the St. Louis Star-Times noted, “230 pounds of man” _ with thick legs and trunk.

From the moment the Cardinals signed him, in 1945, Bilko intrigued with his power. He was big _ 6-foot-1 and, as the St. Louis Star-Times noted, “230 pounds of man” _ with thick legs and trunk.