Getting dealt by a World Series champion put Dave Duncan and George Hendrick on a course toward helping the Cardinals win three World Series titles.

On March 24, 1973, the Athletics traded Duncan and Hendrick to the Indians for Ray Fosse and Jack Heidemann.

Duncan, a catcher, and Hendrick, an outfielder, played in the 1972 World Series for the Athletics, who prevailed in seven games against the Reds. Each wanted to be traded, but for a different reason. Duncan felt unappreciated and feuded with Athletics owner Charlie Finley. Hendrick wanted a chance to play every day.

The trade to Cleveland gave Duncan and Hendrick the opportunities they sought and positioned them for success with World Series champions in St. Louis _ Duncan as a coach for the 2006 and 2011 Cardinals and Hendrick as a player for the 1982 club.

Fed up

Duncan was the Athletics’ Opening Day catcher in 1972, slugging a home run against Bert Blyleven, but Gene Tenace replaced him in the last five weeks of the season. Though Duncan hit for power (19 home runs) and ranked second among American League catchers in fielding percentage (.993) in 1972, he batted .218.

Tenace was the starting catcher in the first six games of the 1972 World Series and hit four home runs, but manager Dick Williams shifted him to first base for Game 7 and put his best catcher, Duncan, behind the plate. Duncan threw out Joe Morgan attempting to steal second, Tenace drove in two runs, and the Athletics won, 3-2. Boxscore

Duncan, who was paid $30,000 in 1972, wanted $50,000 in 1973, $10,000 more than what Finley offered, The Sporting News reported. When Duncan remained unsigned during 1973 spring training, the Athletics looked to trade him, an action Duncan welcomed.

“I didn’t have a very good relationship with Finley,” Duncan said to The Sporting News. “We didn’t share the same philosophy. One of the things I’ve learned from Finley is how I don’t want to live my life. I consider myself a human being with an identity of my own, and I think he tries to strip this away from everyone surrounding him.

“Part of our bad relationship is that he never took the time to listen to me like a human being, and that’s all I ever wanted him to do _ listen to me.”

Unlimited potential

Hendrick made his big-league debut with the Athletics in June 1971 and primarily was a backup to Reggie Jackson. When Jackson was injured during the decisive Game 5 of the 1972 American League Championship Series, Hendrick replaced him and scored the winning run in the pennant-clinching victory versus the Tigers. Boxscore

With Jackson sidelined, Hendrick started in center in each of the first five games of the 1972 World Series. The Athletics won three of those.

“He’s on the threshold of being a star in this game,” Athletics manager Dick Williams told the Associated Press. “He can run, throw and hit with power to all fields. I’m not afraid to put him anywhere in my outfield. Whenever anyone talks trade with us, they mention Hendrick. We won’t even talk about him.”

Let’s make a deal

The Athletics changed their minds about not trading Hendrick when the Indians expressed a willingness to deal catcher Ray Fosse, a two-time Gold Glove Award winner. Though there were some who thought Fosse’s left shoulder never fully recovered from a 1970 All-Star Game collision with Pete Rose, the Athletics liked the idea of having him behind the plate and moving Tenace to first base.

“I’ve long had an eye on Fosse,” Finley told the San Francisco Examiner. “I consider him second only to Johnny Bench as an all-around outstanding catcher.”

To obtain Fosse, the Indians insisted on Hendrick being part of the deal. “They wouldn’t have gone for the trade, not one bit, if we offered Duncan even up,” Finley said to the Examiner. “Putting Hendrick in the pot was what did it.”

Comparing Hendrick to a young Hank Aaron, Indians manager Ken Aspromonte told The Sporting News, “There is nothing, absolutely nothing, George can’t do if he puts his mind to it.”

Hendrick said he wanted to be traded after Finley told him he’d open the 1973 season in the minors, The Sporting News reported. Duncan told the Examiner, “The A’s soured on Hendrick because they believed him to be lazy, but I don’t feel he is. What’s more, he has marvelous all-around talent.”

Five days after the trade, in a spring training game at Mesa, Ariz., in which orange baseballs were used as an experiment, Hendrick hit three home runs versus the Athletics. Two of the homers came against Catfish Hunter. Fosse also hit a home run in the game against his friend, Gaylord Perry.

Opportunity knocks

With Fosse as their catcher, the Athletics won two more World Series championships in 1973 and 1974. The trade helped Duncan and Hendrick, too. Duncan got to be a leader on the field, and Hendrick got to prove he could be a productive player.

“Being traded was the only answer to my problems,” Duncan told The Sporting News. “I had lost my taste for the game, but now I expect it to be fun again.”

Displaying leadership qualities that would make him a successful coach, Duncan earned the respect of his Indians teammates and manager Ken Aspromonte.

“He knows what he’s doing,” Aspromonte told the Sacramento Bee. “So I let him run things for me on the field. He moves the players around on defense and he always lets me know how the pitchers are doing _ whether to lift them or keep them in. I listen to him because I trust his judgment very much. I admire the fact that he tells the truth. He knows this game, and he doesn’t hesitate to tell me what he sees.”

Hendrick told The Sporting News, “We’re especially better because of Duncan.”

Hendrick was a big contributor, too. On April 17, 1973, he lined a pitch from the Brewers’ Billy Champion that carried 455 feet into the center field bleachers at Cleveland Stadium. Indians pitching coach Warren Spahn told The Sporting News, “We retrieved the ball and, so help me, it was flat where George hit it.” Boxscore

Two months later, Hendrick hit home runs in three consecutive at-bats against the Tigers’ Woodie Fryman, then drove in the winning run in the ninth with a single. Boxscore

Unfortunately, both Duncan and Hendrick fractured their right wrists when hit by pitches. Duncan, struck by Don Newhauser of the Red Sox, was sidelined from June 29 through Aug. 17. Hendrick missed the rest of the 1973 season after being struck by the Royals’ Steve Busby on Aug. 14.

Winning touch

Duncan played two seasons with the Indians, then was traded to the Orioles for Boog Powell in February 1975. (Eleven months later, the Indians reacquired Fosse from the Athletics.)

Hendrick spent four seasons with the Indians, topping 20 home runs in three of those, before being dealt to the Padres.

The Cardinals acquired Hendrick in 1978 and four years later he helped them win a World Series title. Hendrick hit .321 in the 1982 World Series against the Brewers and drove in the winning run in Game 7. Boxscore (Gene Tenace also was a member of that Cardinals championship team.)

Duncan became a prominent pitching coach on teams managed by Tony La Russa. With Duncan as their pitching coach, the Athletics won three American League pennants (1988-90) and a World Series title (1989).

In 1996, La Russa’s first season as Cardinals manager, Duncan was pitching coach and Hendrick was hitting coach. The Cardinals won a division title that year for the first time since 1987.

Hendrick joined the Angels’ coaching staff in 1998. He went on to coach for 14 seasons in the majors, primarily with the Rays.

With Duncan as their pitching coach, the Cardinals won three National League pennants (2004, 2006, 2011) and two World Series championships (2006 and 2011). He spent 34 years in the majors as a coach.

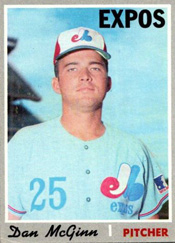

A left-handed pitcher, McGinn did some of his best work against the Cardinals during his first full season in the majors with the 1969 Expos, a National League expansion team.

A left-handed pitcher, McGinn did some of his best work against the Cardinals during his first full season in the majors with the 1969 Expos, a National League expansion team. So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves.

So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves. On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers.

On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers. In 1957, Cardinals general manager Frank Lane was ready to deal Ken Boyer to the Pirates for Thomas and third baseman Gene Freese. When the deal got put on hold by Cardinals hierarchy, Lane quit and became general manager of the Cleveland Indians.

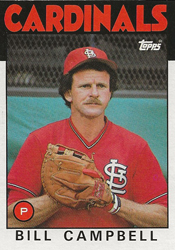

In 1957, Cardinals general manager Frank Lane was ready to deal Ken Boyer to the Pirates for Thomas and third baseman Gene Freese. When the deal got put on hold by Cardinals hierarchy, Lane quit and became general manager of the Cleveland Indians. Campbell signed with the Red Sox instead of the Cardinals in November 1976.

Campbell signed with the Red Sox instead of the Cardinals in November 1976.