Rudy May pitched 16 years in the majors. He never appeared in an All-Star Game, and he lost more than he won, but at times he nearly was unhittable, performing on a par with teammates such as Nolan Ryan, Catfish Hunter and Jim Palmer.

One of May’s nicknames was The Dude. He got it, the Baltimore Sun noted, because of “his funky wardrobe” and “unflappable optimism.”

One of May’s nicknames was The Dude. He got it, the Baltimore Sun noted, because of “his funky wardrobe” and “unflappable optimism.”

He was an interesting dude for more reasons than that though. His boyhood friend was Joe Morgan, the future Hall of Fame second baseman. May’s first marriage was to a rhythm and blues singer. When he wasn’t playing baseball, May worked as a licensed commercial scuba diver.

Though he spent most of his baseball career in the American League, the Cardinals saw plenty of him during a stint with the Montreal Expos and sought to sign him when he became a free agent.

Early journeys

Though born in Kansas, May was raised in Oakland. That’s where he and Joe Morgan became friends. They’d go to Arroyo Viejo Park near their homes and “we’d pitch and catch for hours,” May recalled to the Montreal Gazette. May and Morgan also were baseball teammates at Castlemont High School.

A left-hander, May was with four organizations in his first three seasons as a pro. He was 18 when the Twins signed him in November 1962. They sent him to Bismarck, N.D., and, though he won 11 and struck out 173 in 168 innings there, he also walked 120 and threw 25 wild pitches.

After a season (1964) in the White Sox system, May was traded to the Phillies, who flipped him to the Angels for Bo Belinsky.

May, 20, made the 1965 Angels’ Opening Day roster as a starter. “We never had any question about Rudy’s stuff being major league,” Angels pitching coach Marv Grissom told the Oakland Tribune. “The only question is his control.”

In his big-league debut, May was matched against Detroit’s Denny McLain. The rookie held the Tigers hitless until Jake Wood doubled with one out in the eighth. May completed nine innings, striking out 10 and allowing the one hit, but the Tigers won in the 13th. Boxscore

In his next appearance, a start versus the Yankees and Mel Stottlemyre, May gave up his first home run, a Mickey Mantle solo shot, and lost, 1-0. Boxscore

Treasure hunts

During that 1965 season, outfielder Leon Wagner introduced May to Eleanor Green, a singer with the group The Superbs.

“She was only 18 and she was singing at this club in L.A. and I thought when I saw her that, ‘whoo-eee _ this was some kind of chick,’ ” May said to the Los Angeles Times. “She’d had these two hit records that year _ ‘Baby, Baby All The Time,’ and ‘Baby’s Gone Away‘ … I really came on strong. She showed me who the real pro was. She put me off good.

“Later that year, I was peddling my threads _ you know, just walking around, cooling it _ in Hollywood when I stopped at this club and saw this same girl. I sent a note backstage and she came out to met me. It was different this time, man … Three weeks later, we flew to Las Vegas and got married.”

While his personal life was on the upswing, May’s pitching career hit a sour note. He hurt his shoulder, developed arm problems and was demoted to the minors.

Limited to 35 innings pitched in 1966 and 84 in 1967, May “admits he thought about saying goodbye to baseball” until his wife convinced him to continue, the Los Angeles Times reported.

May wanted a backup plan, though. A recreational scuba diver since his teens, May took commercial diving courses in 1967, earned a license and began spending winters “working on salvage and construction projects beneath the sea,” United Press International reported.

Asked about his most dangerous dive, May told the wire service that while working on a salvage project about 400 feet under the surface, “I got the bends and blacked out. I was in a coma in a depression chamber for about six hours.”

On the road again

May spent a third consecutive season in the minors in 1968. Pitching for El Paso, May was 2-7, then performed his own salvage operation, closing with six consecutive wins. The Angels brought him back to stay in 1969.

May’s highest win total for the Angels was 12 in 1972. In a game against the Twins that year, he struck out 16. Rod Carew and Harmon Killebrew each fanned twice. Boxscore

The wins, though, didn’t come often enough. In seven seasons with the Angels, May was 51-76. In June 1974, they shipped him to the Yankees. He won 14 for them in 1975, got traded to the Orioles in 1976 and won 15 that year.

May did even better in 1977, winning 18 for the Orioles and leading the staff in shutouts (four), but after the season he was on the move again, getting traded to the Expos.

His first win in the National League came against the Cardinals. Boxscore

Expected to be a big winner, as he had been with the Orioles, May was mediocre with Montreal. In one stretch, he lost three in a row to the Cardinals, including two in three days. Removed from the rotation by manager Dick Williams, May broke an ankle in July. Given a start against the Cardinals when he returned two months later, May crafted a gem, pitching a three-hitter for the win. Boxscore

He finished the 1978 season with an 8-10 mark, including 3-3 versus St. Louis.

Back in the groove

May was deep in Dick Williams’ doghouse as the 1979 season got underway. As the Montreal Gazette noted, “May was not only out of the rotation, but he wasn’t even called when the Expos needed fifth and sixth starters. If that wasn’t bad enough, he wasn’t used in important relief assignments.”

He asked to be traded but the Expos didn’t oblige. It turned out well for them. Needing relief help in July, Williams called on May and he delivered.

Then, on July 31, May got his first start of the season and came through with a three-hit shutout against the Cardinals.

“There wasn’t any team in the world that could have hit him tonight,” Cardinals manager Ken Boyer told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Cleanup hitter Ted Simmons, unable to get a ball out of the infield, said to the Montreal Gazette, “May has an exceptional curveball and, when he gets it over like he did tonight, he’s virtually unbeatable.”

After watching May blank the Cardinals, scout and former Yankees pitcher Eddie Lopat told the Gazette, “I’ve never seen him pitch better. He’s right back where he was when he won those 18 games with Baltimore. Tonight he had command of all his pitches _ fastball, slider and curve. When he has control of his breaking ball, he’s almost impossible to beat.” Boxscore

For the month of July, May was 4-0 with a 1.44 ERA in 25 innings pitched.

Moved into the rotation in September, May contributed a 10-3 record and 2.31 ERA for the 1979 Expos.

In demand

Seeking left-handed pitching, the Cardinals pursued May and a couple of their former players, John Curtis and Al Hrabosky, in the free agent market.

General manager John Claiborne “expressed serious interest in May and Hrabosky,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

However, May took a three-year deal totaling $1 million from the Yankees. “Our offer was not in the ballpark,” Claiborne confessed to the Post-Dispatch.

After Hrabosky signed with the Braves and Curtis went to the Padres, the Cardinals shifted gears. To fill their left-handed pitching spots, they got free agent Don Hood in March 1980 and acquired Jim Kaat from the Yankees a month later.

Kaat turned out well for the Cardinals, helping them become World Series champions in 1982, and May turned out well for the Yankees. He was 15-5 for them in 1980 and had the best ERA (2.46) in the American League.

May credited Hall of Fame pitcher Whitey Ford, a Yankees spring training instructor, with helping his approach.

“Ford told me I should learn to pitch when I didn’t have it all going for me,” May said to the Montreal Gazette. “I had it in my head that the only way to get guys out was to strike them out. Ford taught me the mechanics of pitching. He showed me how to mix up my fastballs. I’ve always had a good curve, but he showed me how to take something off my curve as well.”

In 1981, May pitched in three World Series games for the Yankees. The next season, when he turned 38, he appeared in 41 games and his ERA was 2.89.

He pitched for the final time in 1983 and completed his career with a 152-156 mark. Jim Rice, who batted .706 (12-for-17) against May, was sorry to see him go. George Brett, a career .174 hitter (4-for-23) versus May, felt differently.

In October 1964, Joe Becker joined the Cardinals as pitching coach on the staff of newly appointed manager Red Schoendienst.

In October 1964, Joe Becker joined the Cardinals as pitching coach on the staff of newly appointed manager Red Schoendienst. Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals.

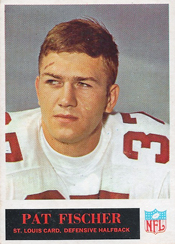

Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals. Listed at 5 feet 9 and 170 pounds _ “Anyone who ever saw him in person knew even those measurements were somewhat exaggerated,” the Washington Post noted _ Fischer shed the blocks of Goliath-like guards and tackles, took down steamrolling fullbacks, and stymied rangy receivers during a 17-year NFL career with the Cardinals (1961-67) and Washington Redskins (1968-77).

Listed at 5 feet 9 and 170 pounds _ “Anyone who ever saw him in person knew even those measurements were somewhat exaggerated,” the Washington Post noted _ Fischer shed the blocks of Goliath-like guards and tackles, took down steamrolling fullbacks, and stymied rangy receivers during a 17-year NFL career with the Cardinals (1961-67) and Washington Redskins (1968-77).

Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate.

Making a leap from the Class A level of the minors to the big leagues, Rose won the starting second base spot with the Reds at 1963 spring training. Once the season began, the player who would become baseball’s all-time hits king looked feeble at the plate.