Studying a football playbook or the intricacies of a defense don’t seem so daunting compared with preparing a dissertation on chemical engineering or doing research for the space program.

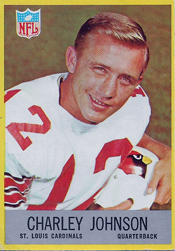

Charley Johnson was a good quarterback for 15 years in the NFL, including from 1961-69 with the St. Louis Cardinals. He led the NFL in completions (223) and passing yards (3,045) in 1964. His 170 career touchdown passes are more than the likes of Troy Aikman (165), Roger Staubach (153) and Bart Starr (152).

Charley Johnson was a good quarterback for 15 years in the NFL, including from 1961-69 with the St. Louis Cardinals. He led the NFL in completions (223) and passing yards (3,045) in 1964. His 170 career touchdown passes are more than the likes of Troy Aikman (165), Roger Staubach (153) and Bart Starr (152).

Perhaps even more impressive is that Johnson earned master’s and doctorate degrees in chemical engineering from St. Louis’ Washington University while playing in the NFL. He used that education to go into business, forming his own natural gas compression company, and then to become head of the chemical engineering department at New Mexico State University.

Basketball boost

As a high school quarterback in his hometown of Big Spring, Texas, Johnson was on a team that rarely passed the ball. No Division I college football program offered him a scholarship, so he enrolled at Schreiner Institute, a school in Kerrville, Texas, that specialized in preparing students for military careers.

After Johnson’s first year at Schreiner, the school dropped its football program. “I’m still not sure whether it was because of me or in spite of me,” Johnson said to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

Johnson stayed and played basketball for the school. At a tournament in Big Spring, New Mexico State athletic trainer Brick Bickerstaff was scouting players. Later that night, at a local chili parlor, Charley’s uncle, Jack Johnson, cornered Bickerstaff and persuaded him to offer his nephew a scholarship, according to Newspaper Enterprise Association. “I was recruited to play basketball,” Johnson told the Albuquerque Journal.

He left Schreiner in mid term and joined the 1957-58 New Mexico State basketball team, playing in two games. “I was very lucky to have received a scholarship anywhere,” Johnson told the Las Cruces Sun-News.

When the basketball season ended, Johnson tried out for the football team at its spring practice. Impressed, head coach Warren Woodson not only gave him a spot on the roster, he named him the starting quarterback.

With Johnson running an offense that featured scoring threats Pervis Atkins, Bob Gaiters and Bob Jackson, New Mexico State was 8-3 in 1959 and 11-0 in 1960, capping each season with a win in the Sun Bowl.

While excelling in football, Johnson also successfully pursued a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering. He said he chose that field after he observed engineers on the site while he was digging ditches for a summer job in Texas. “I knew right then I wanted to be an engineer,” Johnson told the Albuquerque Journal.

Scholar-athlete

While studying New Mexico State game films of Pervis Atkins and Bob Jackson, the NFL Cardinals noticed Johnson, according to Newspaper Enterprise Association. He was drafted by both the Cardinals and the American Football League’s San Diego Chargers. He also got an offer from the Canadian Football League’s Winnipeg Blue Bombers, who were coached by Bud Grant.

The Cardinals made the highest bid, $15,000.

After spending the 1961 Cardinals season as third-string quarterback behind Sam Etcheverry and Ralph Guglielmi, Johnson enrolled in a master’s program at Washington University, taking spring semester courses in engineering analysis, statistics and chemical kinetics.

During the 1962 season, he replaced Etcheverry as starting quarterback.

According to Sports Illustrated, “Johnson didn’t have much use for sleep. His day started at 5:15 a.m. when he wrote a commentary that he delivered on a St. Louis radio station (WIL) at 8. Following the broadcast, he went to classes at Washington U., carrying his playbook with his schoolbooks. Around noon, he headed to practice, and afterward back to class (or to research projects).”

At Washington U., Johnson “can be found leaning over a laboratory table, measuring the viscosity of polymer plastics,” the Globe-Democrat reported.

His specialty was rheology. He told the newspaper, “Rheology involves the science of flow characteristics of various materials. Many plastics, if you melt them, will flow through a small tube and then will expand to be larger than the tube as they come out. I’m trying to figure out why.”

The title of Johnson’s master’s thesis on polymers was titled, “Expansion of Laminar Jets of Organic Liquids Issuing From Capillary Tubes.”

After receiving his master’s in a June 1963 ceremony, Johnson met with teammate Sonny Randle and practiced pass patterns.

At the helm

Johnson led the Cardinals to records of 9-5 in 1963 and 9-3-2 in 1964. Some of his most intense duels were with Cleveland Browns quarterback Frank Ryan, who earned a doctorate in advanced mathematics from Rice in 1965.

Describing that period as “the Charley Johnson era,” Cardinals owner Bill Bidwill said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “It was a team that would innovate. It was a good football team.”

Post-Dispatch columnist Bob Broeg called Johnson “underrated” and added, “He didn’t have the strongest or even the most accurate arm, but he had a knack of getting something out of most scoring opportunities, and he was superb when competing against the two-minute clock at the end of a half or a game.”

In his biography, quarterback Jim Hart, who joined the Cardinals in 1966, said Johnson “studied the game, he knew defenses, and he knew just what he wanted to do. I marveled at the game plan he would call. He didn’t have the overpowering arm. It was more like (Fran) Tarkenton’s. He wasn’t going to break a pane of glass at 50 yards, but he really feathered the ball in there.”

Regarding Johnson’s leadership skills, Hart said, “He had a quiet confidence that I’ve tried to emulate.”

Asked by Post-Dispatch columnist Bernie Miklasz in January 1988 to name the starting quarterback on his all-St. Louis Cardinals team, Bill Bidwill chose Johnson over Hart. “If he hadn’t been hurt, Johnson would have been in the (Pro Football) Hall of Fame,” Bidwill said. “He was an outstanding player.” Video

Rocket man

Johnson suffered a shoulder separation in 1965 and tore ligaments in his right knee in 1966. He was called to active Army duty as a second lieutenant in 1967 and 1968, and assigned to do research on high temperature plastics for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in Hampton, Va. “The project could eventually be important in developing heat- and radiation-resistant material for spacecraft,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

Johnson commuted to Cardinals games during his Army stint but rarely played. When he completed his tour of duty, he continued his NASA research at Monsanto Chemical in St. Louis as a doctoral project for Washington U.

(To the delight of an audience at an April 1967 fundraising banquet in Las Cruces, N.M., Johnson shared the dais with actor Leonard Nimoy, who played Mr. Spock in the “Star Trek” TV series.)

Though Johnson, 30, returned full-time to the Cardinals in 1969, head coach Charley Winner was committed to Jim Hart. Johnson asked to be traded. The Cardinals obliged, sending him and cornerback Bob Atkins to the Houston Oilers for quarterback Pete Beathard and cornerback Miller Farr in January 1970.

After the first of his two seasons with the Oilers, Johnson earned his doctorate in chemical engineering from Washington U., in June 1971. Asked about his dissertation on high-performance plastic resistant to heat and radiation, Johnson told the Texas Star, “My professors and I used a new technique to determine temperatures at which plastic can be molded. It evoked a reaction because there were quite a few plastics not molded at the time of their discovery. No one knew at what temperatures to mold them. People wanted to try our technique, to find out how to mold these plastics which had been shelved.”

Distinguished faculty

In August 1972, the Oilers sent Johnson to the Denver Broncos for a high draft pick. A year later, he led the Broncos to their first winning season since the franchise began in 1960.

After his final season with Denver in 1975, Johnson told United Press International, “I always will feel I’m a Cardinal. I guess that’s because St. Louis is where I started out, and it’s just hard to forget from where you came.”

Johnson became an engineering consultant for a natural gas compressor company in Houston before starting his own firm, Johnson Compression Services, in 1981.

In 2000, he was named head of the chemical engineering department at New Mexico State and continued teaching there until 2010.

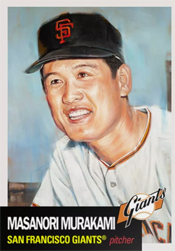

On Sept. 1, 1964, Masanori Murakami, 20, became the first Japanese native to play in the big leagues when he pitched in relief for the Giants against the Mets.

On Sept. 1, 1964, Masanori Murakami, 20, became the first Japanese native to play in the big leagues when he pitched in relief for the Giants against the Mets.

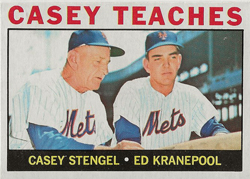

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider. On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes.

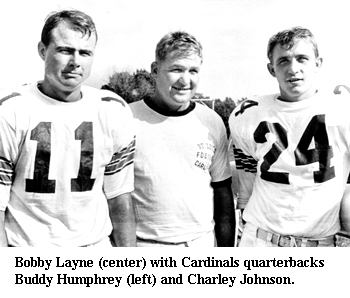

On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes. In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson.

In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson.