(Updated Dec. 27, 2025)

Even as a NFL rookie, Dick Butkus wreaked havoc on the St. Louis Cardinals. In his first regular-season appearance against them, the Chicago Bears middle linebacker intercepted a pass and got into a fight.

An eight-time Pro Bowl selection in nine seasons (1965-73) with the Bears, Butkus prowled the football field “like a hungry grizzly,” the Dallas Morning News noted. “His vicious hits and ferocious demeanor made the middle linebacker position synonymous with pain.”

An eight-time Pro Bowl selection in nine seasons (1965-73) with the Bears, Butkus prowled the football field “like a hungry grizzly,” the Dallas Morning News noted. “His vicious hits and ferocious demeanor made the middle linebacker position synonymous with pain.”

The Associated Press called him “the most devastating middle linebacker in pro football” during his time in the NFL.

In his book “Tarkenton,” Minnesota Vikings quarterback Fran Tarkenton said, “Dick Butkus is the greatest football player I have ever seen. Certainly the toughest … He kept his team in a frenzy every game. He was the most dominating single player I’ve ever seen in a football defense … He was a sight. He snorted and cursed and looked like Godzilla’s brother crouching there in front of the center.”Butkus played in five regular-season games versus the Cardinals, though in one of those he left early because of an injury. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

Humble beginning

Richard Marvin Butkus “was 13 pounds, 6 ounces at birth, the eighth Butkus kid but the first born in a hospital,” according to the Chicago Tribune. He needed to be incubated for a week because his skin turned blue from low oxygen in the blood.

His father, John, an electrician, was a Lithuanian immigrant, according to the Tribune. Mother Emma worked 50 hours a week in a laundry.

At their four-room home on Chicago’s South Side, Butkus slept in an 8-by-10 room with four brothers, according to the Tribune.

Playing football at Chicago’s Vocational High School, Butkus was a 230-pound fullback and linebacker. He chose the University of Illinois for his college career.

(“Northwestern was … well, they ain’t my kind of people,” Butkus told Sports Illustrated in 1964. “Notre Dame looked too hard.”)

Illini head coach Pete Elliott used him as a linebacker and center. In his junior season, when the Illini were Big Ten Conference champions, Butkus made 145 tackles in 10 games, including 23 versus Ohio State.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch described him as “a savage tackler whose body slams led to six fumble recoveries for Illinois” in 1963.

On offense, Butkus was an outstanding center, “with his blocks gouging holes in the enemy line for key short yardage plays.”

Staying home

By the end of his senior season in 1964, Butkus was regarded the top defensive player eligible to turn pro. At that time, the National Football League and American Football League were rivals and held separate drafts.

With the first pick in the 1965 NFL draft, the New York Giants said they considered taking Butkus but went instead for Auburn’s Tucker Frederickson “because he is the best all-around fullback in the country,” team executive Wellington Mara told the Chicago Tribune.

The San Francisco 49ers, picking second, selected North Carolina running back Ken Willard.

Counting their lucky stars, the Bears, who had the third and fourth picks in the first round, went with Butkus and Kansas running back Gale Sayers. “We’ve been after Butkus ever since he led Illinois to the Big Ten title,” Bears head coach George Halas told the Tribune. “We’ve got to have him. He’s a great one.”

(With the 12th pick in the first round, the Cardinals took Alabama quarterback Joe Namath. Opting for Broadway rather than Lindbergh Boulevard, Namath signed with the AFL’s New York Jets.)

The Jets had visions of signing both Namath and Butkus. After the Denver Broncos took Butkus in the AFL draft, they gave their rights to him to the Jets.

“Most people think that I am already sewed up for the Bears,” Butkus said to the Tribune. “They can think it if they want to, but it isn’t so. As far as I’m concerned, it’s still wide open.”

Chicago attorney Arthur Morse, who represented Butkus in negotiations, told the Tribune that the Jets made an offer which “I would have to consider more substantial than that of the Bears.”

Butkus signed with the Bears anyway. “I had a big offer from the New York Jets to go to the AFL,” Butkus told the New York Times, “but I accepted less money to play with the Bears just because they were in Chicago where I grew up.”

Seeing Big Red

In the ninth game of his rookie season in 1965, Butkus faced the Cardinals at Wrigley Field in Chicago. He contributed to a defense that harassed quarterback Charley Johnson, who was sacked four times.

In the fourth quarter, Butkus intercepted a Johnson pass and returned the ball 38 yards to the St. Louis 6-yard line. “Butkus was barging over one Cardinal after another until he finally came crashing down in a heap with guard Ken Gray,” the Tribune reported. “Gray and Butkus had been tiffing, mostly with censored language, all afternoon, but on this occasion it went beyond words.”

Butkus and Gray squared off in a fight, the Post-Dispatch reported. The Bears won, 34-13. Game stats

The next year, with the Bears at St. Louis on Halloween night, Butkus got in for only a few plays before he was injured, according to the Post-Dispatch. An understudy, Mike Reilly, replaced him, but, as the Tribune noted, “Nobody backs up the line with Butkus’ violence.” Johnny Roland rushed for two touchdowns and the Cardinals won, 24-17. Game stats

Butkus and the Bears’ defense were at their best on Nov. 19, 1967, against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field. The Bears intercepted seven passes (five on Jim Hart throws and one each on throws from Charley Johnson and Johnny Roland) and recovered two fumbles in a 30-3 victory.

“Hart, pressured by the Bears blitz and often hit hard after he got off his passes, was off target,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “Several times he threw directly to Bears defenders, who could have had a few more interceptions if they had held the ball.”

Years later, recalling the game for Sports Illustrated, Roland said, “I have a bruise under my lip to this day where he (Butkus) shattered my mask.” Game stats

Making of a legend

Stories about Butkus’ bruising antics became part of NFL lore.

A Bears teammate, Doug Buffone, told Dan Pompei of the Tribune, “I used to line up at the outside linebacker position and look inside. I’d see him hulking over the center. He always had a little blood trickling down his face. I don’t know if he would cut himself or what, but I’d always say to myself, ‘Thank you, Lord, he’s on my side.’ “

With about a minute to go in a game the Bears were losing big, the Detroit Lions had first down and were intending to run out the clock. After the first play, Butkus called a timeout.

“We line up,” Buffone recalled. “He is over the top of the center, Ed Flanagan, then takes five steps back. The center snaps it and Dick comes running 100 mph and just smashes the center. Then he jumped up and called timeout again. He just wanted three more cracks at the center before the game ended.”

In a 1969 exhibition game against the Miami Dolphins, Butkus got into a brawl and was ejected by referee Red Morcroft, who accused Butkus of biting his finger during the melee, causing it to bleed. “If I bit his finger,” Butkus said to United Press International, “he wouldn’t have it on his hand now.”

According to the Tribune, during a game versus the Bears, Lions running back Altie Taylor saw Butkus closing in on him and stepped out of bounds to avoid being walloped. Enraged, Butkus kept chasing him around the perimeter of the field. “That man’s crazy,” Taylor told teammate Charlie Sanders.

The image Butkus created helped make him famous, but it wasn’t the full picture. He read Shakespeare after being introduced to the playwright’s work by Robert Billings, a Chicago Daily News reporter. He also got into acting (he spent half his life residing in Malibu, Calif.) and enjoyed watching classic movies. He married his high school sweetheart in 1963 and they remained together.

“Butkus has been caricatured as a monosyllabic creature who communicates only by grunts and groans and savage growls, a half man, half beast,” the Tribune noted. About his persona as a brute, Butkus told the paper, “I was just saying shit to go along with what everybody wanted. It actually was playing a role.”On the ball

On Sept. 28, 1969, at St. Louis, Butkus blocked a Jim Bakken extra-point attempt (ending the kicker’s streak of converting 97 in a row). Bakken’s left shoulder got battered when Butkus crashed into him. “Sometimes you get mad at that Butkus, but you’ve got to respect him,” Cardinals head coach Charley Winner told the Post-Dispatch. “He makes the big play all the time.”

The Cardinals won the game, 20-17. Game stats

(In an exhibition game between the Bears and Cardinals on Aug. 29, 1970, four 15-yard personal foul penalties were called on Butkus, the Post-Dispatch reported.)

Butkus opposed the Cardinals for the final time on Oct. 29, 1972, at St. Louis. He led a defense that rattled quarterback Tim Van Galder (intercepted three times, sacked twice) in a 27-10 Bears triumph. Game stats

Restricted by a damaged right knee, Butkus, 30, called it quits after the ninth game of the 1973 season.

Butkus had four years remaining on a five-year contract. When he and the Bears were unable to come to terms on a payout, he sued them for breach of contract. In the lawsuit, Butkus said extensive injections of cortisone and other drugs caused irreparable damage to his right knee and that he had not been advised what the long-term effects of the drugs might be, the Associated Press reported.

In 1976, the Bears agreed to pay Butkus $600,000 to settle the suit.

Because of the conflict, Butkus and George Halas didn’t speak for several years. Then, in 1979, Butkus asked Halas, 84, to autograph a copy of the retired coach’s autobiography. According to the Tribune, Halas wrote, “To Dick Butkus, the greatest player in the history of the Bears. You had that old zipperoo.” Video highlights

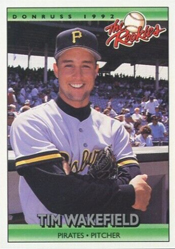

The Cardinals and St. Louis were involved in two other prominent games in Wakefield’s career:

The Cardinals and St. Louis were involved in two other prominent games in Wakefield’s career: On Oct. 12, 1963, the last baseball game played at the Polo Grounds in New York was a charity event called the Latin American Major League Players Game.

On Oct. 12, 1963, the last baseball game played at the Polo Grounds in New York was a charity event called the Latin American Major League Players Game. A right-hander with the skill to pitch a no-hitter or belt a home run, Siebert was acquired by the Cardinals from the Rangers on Oct. 26, 1973, when he was at the back end of his playing career.

A right-hander with the skill to pitch a no-hitter or belt a home run, Siebert was acquired by the Cardinals from the Rangers on Oct. 26, 1973, when he was at the back end of his playing career. After seeing Harrison pitch at spring training in 1973, Phillies ace Steve Carlton told the Philadelphia Daily News, “Just a super, fantastic arm. He could win 20 with that arm just throwing strikes with his fastball.”

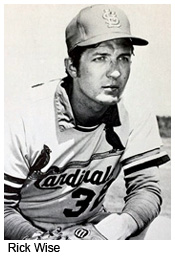

After seeing Harrison pitch at spring training in 1973, Phillies ace Steve Carlton told the Philadelphia Daily News, “Just a super, fantastic arm. He could win 20 with that arm just throwing strikes with his fastball.” In September 1973, the Cardinals won their final five games of the season. Highlighted by the return to health of Bob Gibson and the return to form of Rick Wise and Reggie Cleveland, the Cardinals allowed two runs over 45 innings during the season-ending win streak.

In September 1973, the Cardinals won their final five games of the season. Highlighted by the return to health of Bob Gibson and the return to form of Rick Wise and Reggie Cleveland, the Cardinals allowed two runs over 45 innings during the season-ending win streak.