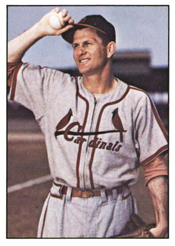

In a lineup featuring future Hall of Famers Stan Musial, Red Schoendienst and Enos Slaughter, it was Erv Dusak who delivered two of the most important hits for the 1946 Cardinals.

On July 16, 1946, Dusak hit a three-run walkoff home run in the ninth, enabling the Cardinals to complete a four-game sweep of the front-running Dodgers.

On July 16, 1946, Dusak hit a three-run walkoff home run in the ninth, enabling the Cardinals to complete a four-game sweep of the front-running Dodgers.

Two months later, in the last week of the regular season, Dusak hit another walkoff home run, a solo shot in the 10th inning against the Reds, for a victory that kept the Cardinals in first place.

Power prospect

An outfielder, Dusak was one of three players who made his major-league debut with the Cardinals in September 1941 after being called up from the Rochester farm team. The others were Musial and third baseman Whitey Kurowski.

In his book “Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story,” Musial said Cardinals executive Branch Rickey didn’t say much to him when he joined the team.

“It was obvious that the player on his mind was Dusak, not Musial, and I can see why,” Musial recalled. “Erv was a strapping right-handed power hitter who ran well, fielded well and threw considerably better than I did.”

Unfortunately for Dusak, pitchers quickly discovered a weakness. “Erv had too much trouble with the breaking ball to last long in the big leagues,” Musial said.

Dusak spent most of 1942 back at Rochester. Following the season, he enlisted in the Army and spent three years (1943-45) in World War II service.

In 1946, the Cardinals opened the season with an outfield of Musial and Slaughter in the corners and Terry Moore in center. Dusak made the team as a reserve.

Swing series

The Dodgers set the early pace in the 1946 National League race, winning eight of their first nine.

When they came to St. Louis for a four-game series in July, the Dodgers (49-28) were 4.5 games ahead of the Cardinals (45-33).

The series began with a doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park on Sunday July 14. The Cardinals won the opener, 5-3. Slaughter drove in four runs, including two on a tie-breaking home run in the eighth, and Ted Wilks pitched four scoreless innings in relief of Johnny Beazley. Boxscore

In the second game, Musial led off the 12th with a walkoff home run against Vic Lombardi, giving the Cardinals a 2-1 triumph. Boxscore

Game 3 of the series was played on Monday night July 15. Schoendienst had three RBI and the Cardinals prevailed, 10-4.

In the third inning, the Dodgers thought their left fielder, Pete Reiser, snared a drive by Slaughter, but umpire Al Barlick ruled Reiser trapped the ball. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher argued and was ejected. Boxscore

The next day, Tuesday July 16, National League president Ford Frick suspended Durocher for five days and fined him $150 for “laying hands on” Barlick during the rhubarb, the New York Daily News reported. Durocher departed St. Louis rather than stick around for that night’s series finale.

Setting the stage

With coach Chuck Dressen as acting manager for Game 4 of the series, the Dodgers took a 4-2 lead into the bottom of the ninth.

“The big crowd, almost silent, appeared to have given up,” the St. Louis Star-Times reported. “Most Brooklyn writers had their stories written.”

Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer told The Sporting News, “It looked like we were goners.”

The Cardinals had the bottom of their order due to face left-hander Joe Hatten.

Hatten got ahead in the count, 1-and-2, to the first batter, Marty Marion, “when the miracle happened,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted.

Hatten grazed Marion on the side of his uniform jersey with a pitch, putting him on first.

Clyde Kluttz, a catcher acquired from the Phillies in May, singled to left, moving Marion to second.

After Dyer sent Dusak to bat for pitcher Howie Pollet, Dressen went to the mound to talk to Hatten. A right-hander was ready in the bullpen, but Dressen stuck with Hatten, a decision some speculated Durocher would not have made.

Fantastic finish

Dusak, batting .229 for the season, was given the bunt sign. After he failed in his first attempt to bunt successfully, he was permitted to swing away. He lashed at Hatten’s second pitch and fouled it off.

Hatten’s next two pitches missed the strike zone, evening the count at 2-and-2. He came back with a fastball and Dusak connected.

“The wallop rang out like a pistol shot,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

According to the Star-Times, “There was a terrific crack and everybody knew at once it was all over.”

The ball carried over the left-field wall and landed 10 rows up in the bleachers, turning the two-run deficit into a 5-4 victory and a series sweep. Boxscore

“Frenzied spectators unloosed a thunderous shout and kept it up for many minutes,” the Globe-Democrat reported. “So jubilant were the Cardinals players that they gathered at the plate and almost mobbed Dusak as he scored.”

The New York Daily News noted, “The Dodgers, with their chins sunk against their chests, trudged forlornly off the field, while all around them Redbird fans joined the St. Louis players in whistling, stomping and jumping with joy.”

Dusak was “as happy as a youngster who had just seen Santa Claus for the first time,” the Globe-Democrat declared.

In the locker room, a young bleacher fan showed up with the home run ball and presented it to Dusak, the Star-Times reported.

“He hit one of the most beautiful home runs I ever expect to see,” Dyer told The Sporting News.

Encore performance

By sweeping the series, the Cardinals (49-33) moved within a half-game of the Dodgers (49-32).

“No series played by the Dodgers all season gave them more of a jolt,” Dyer said to The Sporting News.

The Cardinals and Dodgers waged a fierce fight for first place the remainder of the season.

On Sept. 24, the Cardinals (94-55) held a half-game lead over Brooklyn (94-56) heading into a game against the Reds at St. Louis.

The Reds started Johnny Vander Meer, the left-hander who pitched consecutive no-hitters in 1938.

Vander Meer limited the Cardinals to two singles through eight innings and took a 1-0 lead into the ninth, but Musial tied the score with a two-out RBI-single.

In the 10th, Dusak batted with none on. Working the count to 3-and-1, he got a fastball and pulverized it. The ball cleared the wall in left and “landed only a few feet in front of the concession stand at the back of the bleachers,” the Globe-Democrat reported.

Dusak’s second walkoff home run of the season gave the Cardinals a 2-1 victory and put them a game ahead of the Dodgers with four to play. Boxscore

Mobbed again by his teammates, Dusak was carried off the field on the shoulders of Dyer and coach Mike Gonzalez, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported.

Change in plans

More drama followed. The Cardinals lost three of their last four games and the Dodgers won two of four, leaving the clubs tied for first at the end of the regular season. A best-of-three playoff was held and the Cardinals won the first two games, clinching their fourth pennant in five years.

The Cardinals then prevailed in a seven-game World Series versus the Red Sox.

Dusak hit .240 with nine home runs for the 1946 Cardinals. As a pinch-hitter, he was 4-for-10. Three of the hits were home runs.

In 1947, Dusak batted .284 for the Cardinals, but slumped to .209 in 1948. He decided to become a pitcher and returned to the minors in 1949.

Dusak pitched in 14 games for the Cardinals in 1950 and five more in 1951 before he was traded to the Pirates.

The Dodgers got a bit of revenge on May 22, 1951, when Gil Hodges hit a grand slam against Dusak. Boxscore

Dusak’s big-league career statistics: .243 batting average, 24 home runs, 0-3 pitching record, one save, 5.33 ERA.

On July 7, 1941, Dean quit as Cubs coach and signed a three-year deal with Falstaff Brewing to call Cardinals and Browns home games on St. Louis radio station KWK.

On July 7, 1941, Dean quit as Cubs coach and signed a three-year deal with Falstaff Brewing to call Cardinals and Browns home games on St. Louis radio station KWK. In July 1961, White achieved an unprecedented slugging feat against the Dodgers, then tied a major-league base hit record held by Ty Cobb.

In July 1961, White achieved an unprecedented slugging feat against the Dodgers, then tied a major-league base hit record held by Ty Cobb. On July 6, 1961, Hemus was ousted and replaced by coach Johnny Keane.

On July 6, 1961, Hemus was ousted and replaced by coach Johnny Keane. A left-handed pitcher who was born and raised in Clinton, Hilgendorf was 18 when he signed with the Cardinals in 1960. He was 27 when he finally got to pitch for them in the big leagues in 1969.

A left-handed pitcher who was born and raised in Clinton, Hilgendorf was 18 when he signed with the Cardinals in 1960. He was 27 when he finally got to pitch for them in the big leagues in 1969.