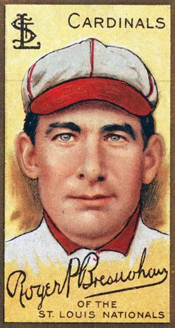

Trying to inspire a ballclub that had become accustomed to losing, Roger Bresnahan was willing to do whatever it took for the Cardinals to win, even if it meant playing second base.

Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates.

Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates.

According to researcher Tom Orf, Bresnahan is one of six Cardinals who have played both at catcher and at second base in the same game. The others: Art Hoelskoetter (1907), Jose Oquendo (1988), Scott Hemond (1995), Tony Cruz (2011) and Pedro Pages (2025).

Quality catcher

A 5-foot-9 scrapper, Bresnahan made his mark with the Giants, displaying the same kind of intensity as the club’s manager, John McGraw.

In the 1905 World Series, Bresnahan caught four shutouts _ three from Christy Mathewson; the other from Joe McGinnity _ in wins against the Athletics. Bresnahan also produced a .500 on-base percentage in that Series, with five hits, four walks and two hit by pitches in 22 plate appearances.

Two years later, Bresnahan became the first catcher to wear shin guards and brought other protective gear innovations, including a rudimentary batting helmet, to the sport, according to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Cardinals, who had the worst record in the majors (49-105) in 1908, acquired Bresnahan, 29, after the season and made him player-manager, giving him the task of injecting fight and hustle into the moribund ballclub.

As a syndicated item in The Cincinnati Post noted in 1911, Bresnahan “is a fighter, and dead anxious to make fighters of others. That’s why he keeps after his men all the time _ to keep them in a fighting mood while on the diamond.”

The Cardinals got a little bit better in each of Bresnahan’s first two seasons as player-manager _ 54-98 in 1909 and 63-90 in 1910 _ but he was looking for greater improvement in 1911. That also was the year Helene Britton took over the Cardinals as the first woman to own a major-league team.

Cincinnati commotion

Determined to establish an aggressive tone early on, Bresnahan gave the Reds a steady stream of trash talk from behind the plate during an April 18, 1911, game at Cincinnati. As the Cincinnati Enquirer put it, “Bresnahan had been using a great deal of coarse language and the Reds claim that his remarks were such that they could not be passed by unnoticed.”

On their way to the clubhouses after the game, Bresnahan and Reds left fielder Bob Bescher continued jawing at one another. “Both men were thoroughly angry,” the Enquirer noted. Bescher threw a punch, socking Bresnahan “flush on the mouth,” The Cincinnati Post reported. “Blood squirted right and left like thick spray from a wind-blown fountain.”

Bresnahan retaliated and the two engaged in what the Enquirer described as “a ferocious fistfight” before Bescher’s teammates, shortstop Dave Altizer and first baseman Dick Hoblitzell, joined in. According to the St. Louis Star-Times, though Altizer and Hoblitzell appeared to be trying to separate the men, “in reality they were taking sly punches at Bresnahan.”

Bresnahan fought back until police and other players broke up the melee, the Star-Times reported.

“Bescher hit at me and, of course, I came back,” Bresnahan told the St. Louis newspaper. “Then Hoblitzell and Altizer broke into the fray. I attended to them. The Cincinnati fans then tried to get us, but the police stopped the doings.”

Bescher said to the Star-Times, “Bresnahan had been goading me all afternoon to the point where I lost my temper. I did not need any help from Altizer and Hoblitzell, but as fellow teammates they felt called upon to interfere.”

The brouhaha made the headlines but another significant story was the injury suffered by Cardinals second baseman Miller Huggins in the game.

With two outs and the bases loaded in the eighth inning, the Reds’ Johnny Bates looped a fly ball to short right. Huggins, first baseman Ed Konetchy and right fielder Steve Evans all chased after the ball. As Huggins made the catch, Konetchy and Evans collided with him. Huggins injured a leg and had to remain in Cincinnati for treatment while the Cardinals returned to St. Louis. Boxscore

Rough and tumble

Beginning a homestand with four games against the Cubs, Bresnahan replaced Huggins with rookie Wally Smith at second base. Smith started two games, but then third baseman Mike Mowrey became bedridden with a severe cold. So, Bresnahan shifted Smith to third and put another rookie, Dan McGeehan, at second for the final two games of the Cubs series. The Cubs swept all four, dropping the Cardinals’ record to 2-5.

Then the Pirates came to town. In 1910, the Cardinals lost 17 of 21 against Pittsburgh. Bresnahan was determined to show the Pirates his 1911 club wasn’t intimidated by them, but three regulars (Steve Evans, Miller Huggins and Mike Mowrey) were sidelined and Bresnahan was playing with a bum knee “swollen to almost twice its normal size,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

The series opener on Monday afternoon, April 24, 1911, at Robison Field in St. Louis was played with the intensity of a pennant race showdown. Pirates runners were tagged out at the plate by Bresnahan in the second and in the sixth.

In the seventh, the Cardinals’ Jack Bliss batted for Dan McGeehan, then stayed in the game at catcher as Bresnahan moved to second base. (He had filled in at second for nine games late in the 1909 season.)

With the Pirates ahead, 5-4, in the eighth, Honus Wagner was on third when Dots Miller tried a suicide squeeze bunt. He tapped the ball toward first but Ed Konetchy got to it quickly and flipped to Bliss. Wagner tried to knock over the catcher, but Bliss blocked the dish and tagged out The Flying Dutchman.

The Cardinals tied the score in the bottom half of the eighth and the game advanced to extra innings.

In the last half of the 11th, Bresnahan punched a single to right and Rebel Oakes moved him to second with a sacrifice bunt. Bliss followed with a tapper to pitcher Lefty Leifield, who fielded the ball and threw to rookie first baseman Newt Hunter.

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Bliss “deliberately threw himself at Hunter, knocking him on his back.” The ball fell from Hunter’s grasp and rolled away as he writhed on the ground in agony. Bresnahan, who had reached third, streaked to the plate and scored the winning run.

“Bliss undoubtedly intentionally knocked Hunter down,” The Pittsburgh Press declared. “Bliss could have veered to the right instead of throwing his entire weight upon the Pirates’ first baseman. The Cardinals are evidently being taught by Bresnahan to be aggressive.”

Though Hunter dropped the ball, rookie umpire Bill Finneran ruled that Bliss was out for interference but allowed Bresnahan’s run to count. As the Post-Gazette noted, “If he called Bliss out for interference, why did he permit Bresnahan to move up on the play? Bresnahan should have been sent back to third, where he started from after Hunter had been rendered helpless.” Boxscore

Off the rails

Bresnahan and his Cardinals players faced a far more dire challenge three months later in July 1911 when they boarded the Federal Express train at Philadelphia’s Broad Street Station for a 10-hour ride to Boston.

Here’s an account by Tom Shieber, senior curator of the Baseball Hall of Fame:

“Originally, the ballplayers occupied a pair of Pullman sleepers located near the front of the train, close behind the 10-wheel locomotive and a U.S. Fishery coach. The position wasn’t ideal. Amid the sweltering heat that saw the mercury rise to 100 degrees that day, it was nearly impossible to sleep with the car windows closed, but opening the windows only made matters worse, letting in the unpleasantness of engine cinders and the stench of baby trout.

“The engine had been reduced to a mound of twisted metal and glowing coals. Behind the ruins of the engine lay a melee of crushed cars haphazardly strewn about, their structures mangled into splinters of wood and piles of iron.

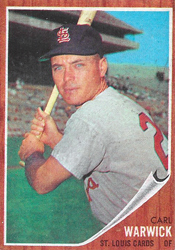

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day.

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day. One hundred years ago, in April 1925, Reds owner Garry Herrmann and seven others associated with the Reds Rooters fan club were arrested at the Hotel Statler for possessing real beer.

One hundred years ago, in April 1925, Reds owner Garry Herrmann and seven others associated with the Reds Rooters fan club were arrested at the Hotel Statler for possessing real beer. Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended.

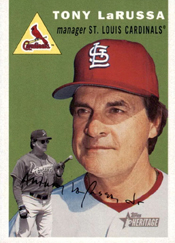

Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended. “At the end of nine years, the A’s had given me permission to interview with the Red Sox, and I was going to Boston,” La Russa recalled to Cardinals Yearbook in 2014. “We even had a discussion about free agents … The one free agent we wanted was

“At the end of nine years, the A’s had given me permission to interview with the Red Sox, and I was going to Boston,” La Russa recalled to Cardinals Yearbook in 2014. “We even had a discussion about free agents … The one free agent we wanted was  Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.