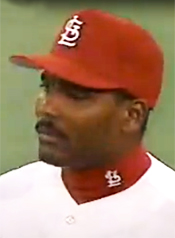

During his time with the Cardinals, Juan Gonzalez lived up to his nickname, but not in the way he and the team hoped.

Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended.

Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended.

In his heyday with the Rangers, Gonzalez was called Juan Gone because balls he hit frequently were sent into orbit and gone out of sight.

When he came to the Cardinals, though, Gonzalez, 38, looked different than he did in his prime. Gone was the bulk he had when he twice led the American League in home runs. Gone was a lot of the swagger, too.

Suspected in the 1990s of using banned performance-enhancing steroids to help him become one of the most powerful hitters, Gonzalez was trying to return to the majors for the first time in three years. The Cardinals, a haven for players linked to performing-enhancing drugs, welcomed him.

Great expectations

“Using a broomstick as a bat and a bottle cap as a ball on the dusty streets of Vega Baja,” Gonzalez developed into a baseball standout as a youth in Puerto Rico, according to the Los Angeles Times. His boyhood nickname was Igor because of his fascination with a professional wrestler of the same name.

At 16, when he was signed by Rangers scout Luis Rosa in May 1986, Gonzalez was “tall and gangly but with athleticism and serious bat speed,” according to MLB.com’s T.R. Sullivan.

The Rangers brought Gonzalez to Florida, where he was introduced by scouting director Sandy Johnson as the “next Babe Ruth,” and put in the outfield alongside 17-year-old Sammy Sosa on their Gulf Coast League rookie team. As Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Randy Galloway noted, “Babe Ruth’s bat had to have been heavier than young Juan.”

Three years later, Gonzalez, 19, made his big-league debut. He was 22 when he won his first American League home run crown. In April 1994, the Fort Worth newspaper did a story speculating whether Gonzalez would break Hank Aaron’s career record of 755. Gonzalez had 121.

Gonzalez also twice received the AL Most Valuable Player Award _ in 1996 (.314 batting mark, 47 homers, 144 RBI) and in 1998 (.318, 45 homers, 157 RBI). That 1998 season was his best. Gonzalez had 101 RBI before the all-star break and his final total of 157 were the most in the American League since 1949 Red Sox teammates Vern Stephens and Ted Williams each had 159. Gonzalez also scored 110 runs and produced 50 doubles.

“Juan in a million,” the Fort Worth Star-Telegram declared.

Success didn’t always bring happiness, however. Gonzalez was married and divorced three times before he turned 25. One of the failed marriages was to the sister of Braves catcher Javy Lopez. (A fourth marriage, to pop singer Olga Tanon, also resulted in divorce.)

“His mistakes, I think, were from a lack of education,” Luis Mayoral, the Rangers’ Latin American liaison and Gonzalez’s confidant, told Mike DiGiovanna of the Los Angeles Times. “He didn’t know what he needed to cope with fame and fortune.”

Columnist Randy Galloway noted, “No one who knows Gonzalez calls him a bad person. He’s not. He can be immature, he can pout, he can be unreasonable at times, and he can make stupid decisions.”

He also had a philanthropic side to him. In 1998, Gil LeBreton of the Fort Worth newspaper wrote, “In his old neighborhood on the rugged streets of Vega Baja, Gonzalez has opened a standing account with the local pharmacy. For those who can’t pay for their prescriptions, Juan will buy the medicine.”

Other Gonzalez projects included a $50,000 donation to build a youth ballpark in southeast Dallas; the purchase of Rangers tickets for underprivileged youngsters from 1995-99; donations for every RBI to Literacy Instruction for Texas reading and writing program from 1997-99; a $25,000 donation to help victims of Hurricane George.

Cheating with chemicals

In his book “Juiced,” Jose Canseco said he introduced Gonzalez to banned performance-enhancing drugs when they were Rangers teammates from 1992-94. Canseco said he injected Gonzalez with the steroids. Canseco was traded to the Rangers from the Athletics, where he played for manager Tony La Russa. In his book, Canseco said he injected Athletics teammate Mark McGwire with banned performance-enhancing drugs and witnessed McGwire and Jason Giambi administer needles to one another.

Rangers owner Tom Hicks told the Associated Press in June 2007 that he suspected Gonzalez used banned steroids when he was with the team. “His number of injuries and early retirement just makes me suspicious,” Hicks said.

In the December 2007 Mitchell Report, an investigation into the use of anabolic steroids and human growth hormone in big-league baseball, Gonzalez was linked to a bag of steroids discovered during a search at the Toronto airport in 2001.

The 2001 season was Gonzalez’s last big year in the majors. He hit .325 with 35 homers and 140 RBI for the Indians that season. After that, his body broke down. Injuries to his hamstrings, hands, shoulders and back cut short his seasons with the Rangers in 2002 and 2003, and with the Royals in 2004.

Gonzalez, 35, rejoined the Indians for spring training in 2005 but injured a hamstring while making a catch on the same day that manager Eric Wedge named him the starting right fielder. In his first game back with the Indians on May 31, Gonzalez injured the hamstring again while running to first base in the first inning. He never played in another big-league game.

Hear no evil, see no evil

The big-league totals for Gonzalez included 434 home runs and 1,404 RBI. In February 2007, he told USA Today he hoped to return to the majors and reach 500 homers. “That’s still my goal and I remain confident I will attain it,” he said.

To get himself into condition for a comeback, Gonzalez attended a training program in Puerto Rico operated by ex-Cardinal Eduardo Perez. “He really never stopped playing,” Perez told Derrick Goold of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He looks great, like he hasn’t missed a beat. His legs look strong. Once a hitter, always a hitter.”

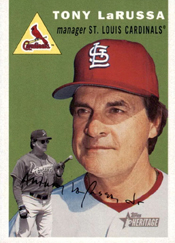

Perez recommended Gonzalez to Cardinals manager Tony La Russa. “You’re going to see a very humble guy,” Perez told the Post-Dispatch. “It’s a lot different than before. He just wants to prove he can still play.”

Intrigued, the Cardinals signed Gonzalez to a minor-league contract in February 2008 and invited him to compete at spring training for a role on the big-league club. The deal called for him to be paid $750,000 if he made the big-league team.

“We all know what he was in his prime,” La Russa told the Post-Dispatch. “He had one of the most gorgeous swings around.”

Cardinals general manager John Mozeliak said to reporter Joe Strauss, “There’s not a great deal of risk involved, but there is the potential for significant upside.”

Actually, there was a risk _ to the Cardinals’ image _ because club management looked like enablers, or protectors, for users of performance-enhancing drugs.

In December 2006, La Russa urged the Cardinals to sign free agent Barry Bonds. Even without Bonds, the Cardinals at 2008 spring training had five players (more than any other team) who were implicated in the Mitchell Report: Rick Ankiel, Ryan Franklin, Troy Glaus, Juan Gonzalez and Ron Villone. Also, La Russa had given Mark McGwire, whose use of banned performance-enhancing drugs created a fraudulent pursuit of the single-season home record, an open invitation to join the Cardinals that spring as an instructor.

Eyes wide shut

Here are excerpts from a February 2008 interview Post-Dispatch columnist Bryan Burwell did with La Russa at spring training:

Burwell: Does it bother you that there’s a perception that you give safe harbor to steroid guys?

La Russa: “No, and I’ll tell you why not … I know there isn’t anything we’ve done in all those years that was _ with one small exception where we stole signs, a little hiccup _ there isn’t anything else that has happened on our ballclubs in Oakland or St. Louis that there’s a hint of illegality. There isn’t anything that we didn’t actively and proactively attempt to do it right.”

Burwell: Does it bother you that you and coach Dave McKay have gained the unflattering label as the so-called godfathers of baseball’s steroids era with your connections to Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire?

La Russa: “That’s one of the crosses you have to bear … Dave McKay has as much or more integrity as any man I’ve met … There’s no chance that what happened officially at Oakland was tainted. Does it mean … when our guys are not in our facilities, not in our weight rooms, that guys didn’t experiment? No.”

Burwell: Would you have cared if you did know they were experimenting?

La Russa: “Yeah, I would care, because when I saw a guy who got stronger quickly without working hard, oh yeah, that implies a lot of other things about what he’s willing to do.”

Burwell: You still don’t believe McGwire used performance-enhancing drugs?

La Russa: “Absolutely not.”

Burwell: Come on.

La Russa: “Absolutely not. If you see Mark today, he still looks like he did then.”

Burwell: No he doesn’t.

La Russa: “Yes he does.”

Asked when he got to camp whether he’d ever used performance-enhancing drugs, Gonzalez told reporter Derrick Goold, “I never used it. I’m clear.”

Assigned uniform No. 22, Gonzalez singled twice and scored a run in the Cardinals’ exhibition opener against the Mets.

In 26 spring training at-bats, Gonzalez hit .308 with one homer (against Johan Santana) and five RBI before straining an abdominal muscle.

Placed on the temporarily inactive list, Gonzalez opted to go home to Puerto Rico. The Cardinals informed him he could return for an extended spring training when he felt ready to play.

“I told him he made a real good impression,” La Russa said to the Post-Dispatch. “I’m disappointed because he could have provided something special to our club.”

The Cardinals didn’t hear back from Gonzalez.

Six years later, in 2014, La Russa was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In an interview he did that year with Cardinals Yearbook, La Russa said McGwire did “a limited amount” of performance-enhancing drugs. Here are excerpts from that 2014 interview:

Cardinals Yearbook: How do you respond to those who say you were an enabler of baseball’s steroids era?

La Russa: “The only way you could know about what was going on was if you ran an investigation … I know on our team you couldn’t be a policeman and get detectives involved. Nobody is going to do that. If something is happening, it’s happening away from the ballpark.”

Cardinals Yearbook: How could it have been handled differently?

La Russa: “That’s the great unknown … All I know is on a personal basis I have no regrets. I don’t feel guilty about any part of it. We did what we could do.”

“At the end of nine years, the A’s had given me permission to interview with the Red Sox, and I was going to Boston,” La Russa recalled to Cardinals Yearbook in 2014. “We even had a discussion about free agents … The one free agent we wanted was

“At the end of nine years, the A’s had given me permission to interview with the Red Sox, and I was going to Boston,” La Russa recalled to Cardinals Yearbook in 2014. “We even had a discussion about free agents … The one free agent we wanted was  Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart.

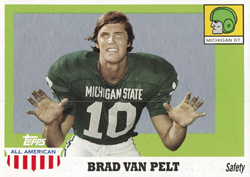

Dubbed the “Frank Sinatra of baseball” for his singing, Mazar, like Ol’ Blue Eyes, was from New Jersey. Sinatra’s hometown was Hoboken, site of the first organized baseball game played in 1846 between the Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine. Mazar grew up in High Bridge, a mere 50 miles from Hoboken but, otherwise, worlds apart. Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport.

Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport. On March 28, 1970, the East-West Major League Baseball Classic was played at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. According to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Saturday afternoon exhibition netted more than $30,000 for two beneficiaries:

On March 28, 1970, the East-West Major League Baseball Classic was played at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. According to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Saturday afternoon exhibition netted more than $30,000 for two beneficiaries: Players from the East divisions of the American and National leagues were placed on an East team. The West team had players from the West divisions of both leagues. That gave fans the chance to see Angels and Dodgers, Mets and Yankees, and Athletics and Giants perform as teammates.

Players from the East divisions of the American and National leagues were placed on an East team. The West team had players from the West divisions of both leagues. That gave fans the chance to see Angels and Dodgers, Mets and Yankees, and Athletics and Giants perform as teammates. In the long history of the franchise, Lee is the only Cardinal to play in just one game for them and have a 1.000 batting average.

In the long history of the franchise, Lee is the only Cardinal to play in just one game for them and have a 1.000 batting average.