In a move more desperate than daring, the Cardinals attempted to bolster their starting rotation by acquiring a retired pitcher who’d been through a bankruptcy, admitted to having been a problem drinker and was thought to have lost velocity on his pitches.

Ron Bryant, a left-hander who followed a 24-12 record for the 1973 Giants with a 3-15 mark in 1974, then went on baseball’s voluntarily retired list, was dealt to the Cardinals in May 1975. Two months later, they released him.

Ron Bryant, a left-hander who followed a 24-12 record for the 1973 Giants with a 3-15 mark in 1974, then went on baseball’s voluntarily retired list, was dealt to the Cardinals in May 1975. Two months later, they released him.

The Cardinals paid a high price to find out Bryant was washed up. A prospect they traded for him, Larry Herndon, developed into one of the National League’s top rookies in 1976, then became a starting outfielder for the 1984 World Series champion Tigers.

Opportunity knocks

In 1965, Giants scout Eddie Montague went to see a California high school infielder, Bob Heise, play for Vacaville. The opposing pitcher, Ron Bryant of Davis, threw a no-hitter.

On Montague’s recommendation, the Giants drafted Bryant in the 22nd round. He signed the day after his graduation but had low expectations for his baseball career. “I just didn’t believe I had the ability to make the big leagues,” he later said to the Atlanta Constitution. “I didn’t think I had the fastball or anything else.”

Bryant didn’t strike out many _ “I can’t. I am just not an overpowering pitcher,” he told the Atlanta newspaper _ but “he pitched cleverly,” Glenn Dickey of the San Francisco Chronicle noted, and made it to the majors with the Giants as a reliever and spot starter.

The Giants’ equipment man, Mike Murphy, nicknamed Bryant “Bear” because of his resemblance to the animal, not the football coach. Bryant was 6-foot and 210 pounds and “looked like a bear, with his chunky build, his way of walking and his curly hair,” Murphy told The Sporting News.

A performance against the Cardinals in April 1971 earned Bryant a spot in the starting rotation. When Frank Reberger developed a shoulder problem and departed after allowing the first two Cardinals batters to reach base, Bryant relieved, pitched nine innings and got the win. “A major turning point,” he told The Sporting News. “If I hadn’t had that opportunity, or hadn’t pitched well, I might have stayed in the bullpen.” Boxscore

Five days later, Bryant pitched a three-hitter against the Pirates for his first shutout. Boxscore

The Cardinals were involved in another pivotal game for Bryant in June 1972. With one out in the eighth inning and the Giants ahead, 3-0, manager Charlie Fox removed Bryant for a reliever. After the Cardinals rallied and won, Bryant criticized Fox for taking him out. Boxscore

In his next start, against the Cubs, Fox left Bryant alone and he pitched a two-hit shutout. As Bryant headed for the dugout after the final out, Fox came onto the field and bowed to the pitcher. Boxscore

Bryant went on a six-game winning streak and finished the 1972 season with a 14-7 record, including four shutouts, and 2.90 ERA.

Good and bad

While Bryant was progressing on the field, he was having trouble away from baseball. The pitcher and his wife filed for bankruptcy in November 1972, the San Francisco Examiner reported.

After a loss to the Cardinals in May 1973, Bryant’s season record was 3-3. Then, while watching game film, he discovered a flaw in how he was releasing the ball. Bryant made a correction and won eight in a row. Video at 9:20

Bryant stacked up wins faster than any pitcher in the league. He won his 20th before September and finished with 24, most for a Giants left-hander since Carl Hubbell had 26 in 1936. The Sacramento Zoo named a 10-month-old sloth bear in honor of the pitcher nicknamed Bear.

It should have been the best of times for Bryant but it wasn’t. He and his wife divorced. Then there was the drinking. Bryant “drank considerably,” Art Spander of the San Francisco Chronicle noted.

During the 1973 season, Charlie Fox found Bryant “lurking in the hotel bar once too often and pushed him out the door,” according to columnist Wells Twombly.

Glenn Dickey of the Chronicle wrote of Bryant’s 24-win season, “There is no question that the attention went to his head. He drank too much and his marriage disintegrated. Nothing he ever did was intended maliciously, but he did a lot of damage to people, including himself.”

“Drinking had been one of my problems,” Bryant told The Sporting News.

Slip sliding away

When Bryant reported to 1974 spring training, “he was desperately overweight,” Wells Twombly reported. “Not only that, he was living from beer to beer and nearly everybody knew it.”

After a Cactus League game in Yuma, Ariz., the Giants took a bus ride across the desert to Palm Springs, Calif. Shortly after 8 p.m., they arrived at the Tropics, a Polynesian-styled resort that featured a coffee shop (regrettably named Sambo’s), two cocktail lounges (The Reef and The Cellar) and a steakhouse (The Congo Room). The place became a celebrity hangout in the 1960s. Victor Mature (who played opposite Hedy Lamarr in “Samson and Delilah”) had a private table in The Congo Room. Elvis Presley and Nancy Sinatra used to relax by the pool.

The pool looked inviting to Bryant. About 11 p.m., the Bear went belly-flopping down a slide, lost control, tumbled off and slammed into the concrete edge of the pool, opening a gash near his right rib cage. Some 30 stitches were required, The Sporting News reported.

Bryant said drinking didn’t cause the mishap (he’d had two beers, the Examiner reported), but that was no solace to Charlie Fox, who called it “an unfortunate, silly accident,” the Examiner reported.

Sidelined for six weeks, Bryant was ineffective when he returned. His 3-15 record included an 0-2 mark against the Cardinals.

“That pool accident threw everything out of whack,” Bryant told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It preyed on my mind. What happened was my own fault, nobody else’s … I have to admit I should have had more dedication.”

Coming and going

In December 1974, Bryant and his wife remarried and he gave up drinking. However, he came to 1975 spring training at close to 220 pounds, The Sporting News reported, and performed inconsistently. “He would pitch well to a couple of batters and then his mind would wander,” the San Francisco Chronicle observed.

Wes Westrum, who replaced Charlie Fox as manager, said Bryant showed “no velocity” on his pitches, The Sporting News reported. Pitching coach Don McMahon concurred, saying Bryant’s “velocity and control were off.”

Just before the season began, Bryant, 27, told the Giants he was retiring.

“I don’t think there’s any chance I’ll change my mind … I’m not really enjoying playing,” he said to the Oakland Tribune.

Two weeks later, Bryant changed his mind. He asked the Giants to reinstate him, but baseball rules required he had to wait until the season was 60 days old before he could pitch in a regular-season game. For Bryant, that meant June 6.

Uninterested in keeping him, the Giants looked to make a trade. To their glee, the Cardinals agreed to give up two prospects, pitcher Tony Gonzalez and outfielder Larry Herndon, to get him. The deal was made on May 9, 1975.

Unsatisfied with the performances of John Denny and 39-year-old Bob Gibson, the Cardinals were looking to revamp their starting rotation. After dealing for Bryant, they acquired Ron Reed from the Braves. Denny was demoted to the minors, Gibson got banished to the bullpen and Bryant and Reed were tabbed to replace them as starters.

To get much-needed work, the Cardinals sent Bryant to extended spring training in Florida. Primarily facing minor-league rookies whose low-level summer leagues hadn’t started yet, Bryant allowed one hit in six innings.

Next, the Cardinals chose him to start in a June 5 exhibition game against their Class AAA team at Tulsa. It was a disaster. Bryant allowed nine runs and 12 hits in 4.1 innings. “Lots of the time, I didn’t have much of an idea of what I was doing out there,” he confessed to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Nonetheless, the Cardinals activated him. Pitching in relief, he faced three batters in his first appearance and allowed three hits. Boxscore

Then came a start against the Pirates. Bryant gave up two home runs _ a two-run wallop by Willie Stargell and a three-run rocket from Rennie Stennett _ and retired just three batters before being relieved by Gibson. Boxscore

Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst saw enough. He removed Bryant from the starting rotation and put Gibson back in.

Given a chance at relief work, Bryant mostly was ineffective. The Cardinals asked him to accept a demotion to Tulsa but he refused. “If he’d have gone down to Tulsa, where he could do some pitching, he could have come back to spring training (in 1976) and helped us,” Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch.

Instead, the Cardinals released Bryant on July 31, 1975. In 10 appearances covering 8.2 innings for them, he was 0-1 with a 16.62 ERA.

Two years after leading the National League with 24 wins, Bryant was finished as a big-league pitcher.

Berra’s playing days certainly appeared to be over in October 1963 when he became manager of the Yankees. “I’ll have enough trouble managing,” he said to the Associated Press in explaining why he was done playing.

Berra’s playing days certainly appeared to be over in October 1963 when he became manager of the Yankees. “I’ll have enough trouble managing,” he said to the Associated Press in explaining why he was done playing. A pair of catchers, Del Rice of the Cardinals and Rube Walker of the Dodgers, were the contestants in what Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a snail versus tortoise match race.”

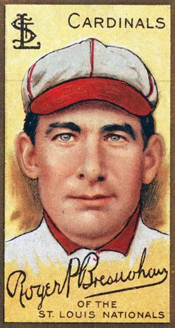

A pair of catchers, Del Rice of the Cardinals and Rube Walker of the Dodgers, were the contestants in what Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a snail versus tortoise match race.” Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates.

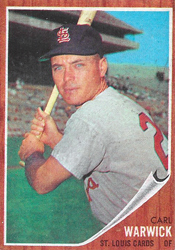

Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates. A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day.

A week before the season ended, Warwick suffered a fractured cheekbone when he was struck by a line drive during pregame drills. He underwent surgery the next day. One hundred years ago, in April 1925, Reds owner Garry Herrmann and seven others associated with the Reds Rooters fan club were arrested at the Hotel Statler for possessing real beer.

One hundred years ago, in April 1925, Reds owner Garry Herrmann and seven others associated with the Reds Rooters fan club were arrested at the Hotel Statler for possessing real beer.