While learning to be a California cowboy, 11-year-old Bill Howerton vaulted from a horse, landed awkwardly and injured an ankle. His left leg was never the same.

Howerton walked with a limp, earning the nickname Hopalong, but eventually developed into a baseball talent, reaching the big leagues with the Cardinals.

Howerton walked with a limp, earning the nickname Hopalong, but eventually developed into a baseball talent, reaching the big leagues with the Cardinals.

A left-handed batter with power, Howerton got the most starts in center field for the 1950 Cardinals, joining an outfield of future Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Enos Slaughter.

Home on the range

Howerton was born and raised in California’s Santa Barbara County. Though often listed as being from the town of Lompoc, Howerton was born in unincorporated Las Cruces, “a spot in the road that has subsequently disappeared” to make way for highway construction, according to the Lompoc Record.

A son of a ranch foreman, Howerton was riding herd in the saddle when he leaped off his horse to close a corral gate, injuring his left ankle. A bacterial or fungal infection set in and doctors informed the youth he had osteomyelitis, an inflammation of bone or bone marrow, The Pittsburgh Press reported.

Howerton underwent four operations. Doctors drilled into the ankle bone to scrape the marrow, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Howerton spent nine weeks in a hospital and used a wheelchair and crutches for two years, the Pittsburgh and St. Louis newspapers reported.

After he recovered, Howerton attended Santa Ynez Valley High School in Solvang, Calif. He played baseball and showed skill as a pitcher. At 16, his parents separated and Howerton helped his mother operate a gas station, according to the Post-Dispatch. He also worked in a brick factory as a press operator, maintaining the machinery that shapes and molds raw materials into bricks.

Baseball became Howerton’s passion. He joined a semipro team, the Lompoc Merchants, played shortstop and earned a partial scholarship to Saint Mary’s College of California. In 1941, he hit .600 and didn’t make an error for the college team, according to the Santa Barbara News-Press.

Accepting an offer from Red Sox scout Earl Sheely, Howerton was assigned to a farm club in Scranton, Pa.

Baseball and romance

In 1943, his first season at Scranton, Howerton was moved from infield to outfield because the stiffness in his ankle prevented him from shifting quickly enough to field grounders to his left, International News Service reported.

After a home game that year, Howerton, 21, was having a late-night snack at Tony Harding’s Diner on Lackawanna Avenue in downtown Scranton. The place was known for baking its hamburger buns extra large to accommodate the fat burgers. Murals on the wall behind the counter depicted classic Lackawanna Railroad passenger trains. According to the Scrantonian Tribune, night owls at the diner often “stayed for breakfast while waiting for the morning paper with the baseball scores and racing results.”

It was there that Howerton met Betty McConnell. They married that year, forming a lifelong bond.

His commitment to the Red Sox wasn’t nearly as strong. After three seasons in their farm system, Howerton quit because of poor pay, saying he earned more operating a bulldozer for his father-in-law’s construction business in Scranton, the Post-Dispatch reported.

When the Cardinals’ Columbus (Ohio) farm team offered him a pay hike to resume his baseball career, a trade with the Red Sox was arranged and Howerton, 24, became a member of the St. Louis system in July 1946.

Columbus manager Hal Anderson “went to work on Howerton’s batting,” Russ Needham of the Columbus Dispatch reported. “The way he held his bat gave (Howerton) a loop in his swing. He could hit the tar out of a low pitch or one (that was) belt-high, but the pitchers were giving him few of those. Instead they’d pitch him around the shoulders, which forced him to loop with the bat to get his swing level as he met the ball.”

After eliminating the loop and learning to lay off high pitches, Howerton put up big numbers for Columbus _ .299 batting average, 25 home runs, 114 RBI in 1948; .329 batting mark, 21 homers, 111 RBI in 1949. He also developed a reputation as a steady outfielder.

The 1949 Cardinals, battling the Dodgers for first place, figured Howerton could help in the pennant stretch. He was called up to the majors in September.

Howerton contributed to a key win against the Dodgers in the first game of a doubleheader on Sept. 21, 1949, at St. Louis. Scoreless in the bottom of the ninth, the Cardinals had runners on first and second, none out, when Howerton turned a bunt into a single, loading the bases. Joe Garagiola followed with a hit, giving the Cardinals a 1-0 win. Boxscore

Though the Dodgers won the second game, the split kept the Cardinals in first place, 1.5 games ahead of Brooklyn, with eight to play. In the end, the Dodgers played better, winning the pennant with a 97-57 record and finishing a game ahead of the Cardinals (96-58).

Opportunity knocks

Howerton, 28, began the 1950 season primarily as a Cardinals pinch-hitter. On May 1 at St. Louis, the Dodgers led, 2-1, when the Cardinals put runners on first and second, two outs, in the bottom of the ninth. Catcher Del Rice was due up, but manager Eddie Dyer wanted a left-handed batter to face knuckleball specialist Willie Ramsdell.

“Can you hit a knuckleball, kid?” Dyer asked Howerton.

Howerton replied, “I can hit anything.”

Dyer liked that answer. Though he had other left-handed batters available, such as Joe Garagiola, Solly Hemus and Harry Walker, Dyer sent Howerton to the plate. He drilled a single to right, scoring Enos Slaughter from second with the tying run and moving Red Schoendienst to third. Ramsdell uncorked a wild pitch to the next batter, enabling Schoendienst to scamper home with the winning run. Boxscore

Howerton’s timely hitting convinced Dyer to start him against right-handers. Though Howerton made starts at all three outfield positions, he primarily platooned with Chuck Diering in center.

“Even now, with his left ankle stiff and the left leg thinner in circumference than the right, Howerton runs with a hopalong limp,” Bob Broeg reported in The Sporting News. “Still, he’s among the faster Cardinals and, next to Musial, has the best long ball power among the Redbirds.”

Howerton hit .281 for the 1950 Cardinals, with 59 RBI in 313 at-bats. He totaled 20 doubles, eight triples and 10 home runs.

Keep on truckin’

Marty Marion replaced Eddie Dyer as Cardinals manager and figured Howerton for a bench role in 1951. On June 15, Pirates general manager Branch Rickey sent Wally Westlake and Cliff Chambers to the Cardinals for Howerton, Joe Garagiola, Howie Pollet, Ted Wilks and Dick Cole.

Howerton got to play center in a Pirates outfield with Ralph Kiner and Gus Bell. “Howerton is a complete outfielder,” Pirates manager Billy Meyer told The Pittsburgh Press. “He’s a corking hitter, a fine outfielder and owns an arm that commands respect.”

The next year, though, the Pirates wanted to make room in the outfield for a hometown prospect, 19-year-old Bobby Del Greco. Howerton was odd man out.

In May 1952, he was acquired by the Giants, who were seeking outfield depth after Willie Mays entered military service. “I’m glad to have him,” Giants manager Leo Durocher told the New York Daily News. “He does everything well and I know he can handle center field. He can run and throw and he’ll hit pretty good, too.”

About a month later, though, Howerton was back in the minors for good.

He had one more big season (32 home runs, 106 RBI for Oakland of the Pacific Coast League in 1953) before going into the trucking business.

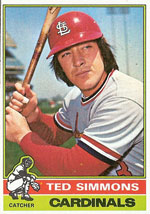

Big-league baseball, though, wasn’t hip to the grooves Simmons made in his bats, even though the Cardinals catcher claimed the alterations were done to preserve the lumber, not enhance his hitting.

Big-league baseball, though, wasn’t hip to the grooves Simmons made in his bats, even though the Cardinals catcher claimed the alterations were done to preserve the lumber, not enhance his hitting. Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals.

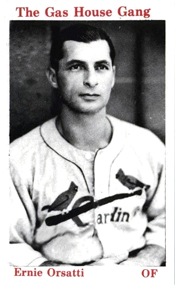

Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals. Confronted by spectators who stormed the field “snatching caps, gloves and even trying to hold the players while attempts were made to steal their shoes from their feet,” the reigning World Series champions “were thankful to escape with their lives,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

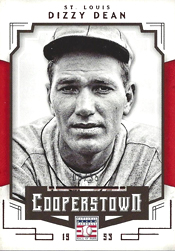

Confronted by spectators who stormed the field “snatching caps, gloves and even trying to hold the players while attempts were made to steal their shoes from their feet,” the reigning World Series champions “were thankful to escape with their lives,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. On June 4, 1935, at Pittsburgh, the St. Louis ace experienced an unlucky inning against the Pirates. Dean blamed the umpire and the Cardinals fielders. An argument ensued in the dugout and it nearly led to a fight.

On June 4, 1935, at Pittsburgh, the St. Louis ace experienced an unlucky inning against the Pirates. Dean blamed the umpire and the Cardinals fielders. An argument ensued in the dugout and it nearly led to a fight. One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with

One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with