(Updated Aug. 28, 2024)

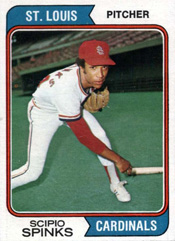

Scipio Spinks had the talent and charisma to become a renowned player for the Cardinals, but injuries derailed his promising pitching career.

On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons.

On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons.

The dispatching of Reuss was initiated by the Cardinals’ owner, Gussie Busch, but general manager Bing Devine nearly straightened out the mess when he obtained Spinks.

A right-hander with an exceptional fastball and an ebullient personality, Spinks quickly made a mark.

Notable name

Born and raised in Chicago, Scipio Spinks traced his first name to Scipio Africanus Major, a Roman general who defeated Carthage leader Hannibal in the Battle of Zama on the north coast of Africa in 202 BC.

“Spinks said the first male child in his father’s family has been named Scipio for a number of generations,” The Sporting News reported.

Spinks told the Associated Press the family name spanned a minimum of six generations. “I’m at least Scipio Spinks the sixth,” he said.

The south side of Chicago, where Spinks was from, was White Sox territory, but he rooted for the Cubs. “I liked Lou Brock a lot, even when he wasn’t hitting, because he could run and so could I,” Spinks told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “but my first favorite was Ernie Banks.”

(When Spinks joined the Cardinals, he and Brock became teammates.)

A standout high school athlete who ran the 100-yard dash in 9.5 seconds, Spinks said he wrote to the Cubs, asking for a tryout, but they were uninterested. He was 18 when he signed with the Astros as an amateur free agent in 1966.

Spinks made his major-league debut with the Astros in September 1969. He got called up again in May 1970 and made five appearances, including a start against the Cardinals in which he gave up a home run to Dick Allen. Boxscore

The Astros had two terrific prospects, Spinks and 6-foot-8 J.R. Richard, at their Oklahoma City farm team in 1971. Richard was 12-7 with 202 strikeouts in 173 innings. Spinks was 9-6 with 173 strikeouts in 133 innings.

“Oklahoma City foes say Scipio Spinks throws harder than teammate J.R. Richard,” The Sporting News reported.

Spinks pitched in five September games for the 1971 Astros and beat the Braves for his first win in the majors.

Idiot wind

At spring training with the 1972 Astros, Spinks earned a spot in a starting rotation of Don Wilson, Larry Dierker, Dave Roberts and Ken Forsch. Roberts gave Spinks the nickname “Bufferin” because his fastball worked faster than aspirin, The Sporting News reported.

Meanwhile, Reuss, a St. Louisan who had 14 wins for the 1971 Cardinals, came to spring training unsigned in 1972. A petulant Busch threw a fit in February when pitcher Steve Carlton dared to negotiate a contract rather than bend to Busch’s will. Busch ordered Devine to trade Carlton.

Next on Busch’s Schlitz list was Reuss. In addition to trying to negotiate an upgrade on the $20,000 salary offered by the Cardinals, Reuss, 22, made the mortal sin of growing a moustache. Busch was apoplectic. He pressured Devine to deal Reuss, too.

Devine announced the trade at 6 p.m. following the Cardinals’ Opening Day loss to the Expos before 7,808 spectators at Busch Memorial Stadium. Boxscore

Fitting in

Spinks, 24, was put into a starting rotation with Bob Gibson, Rick Wise and Reggie Cleveland. He lost his first start, then won his next three decisions, including a May 9 game against the Astros. Boxscore

“His fastball was just dynamite,” Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons told The Sporting News. Brock said, “He seems to be able to challenge the hitters consistently better than most pitchers with his experience.”

Brock and Gibson took a liking to Spinks, whom The Sporting News described as “a great crowd-pleaser and a bubbling personality.” Their good-natured needling became a clubhouse staple.

“Big-name stars are the easiest to kid,” Spinks told the Associated Press. “Brock, Gibson, Joe Torre – people of that caliber – take it, then they dish it back. It keeps everybody smiling.”

In his book “Stranger to the Game,” Gibson said, “I admired Spinks’ energy and appreciated the fact he apparently thought he could become a better pitcher by hanging around me.”

Spinks bought a large stuffed gorilla in a hotel gift shop, dubbed it “Mighty Joe,” and displayed the good-luck charm in his clubhouse locker. The other players eventually adopted Mighty Joe as a team mascot.

After beating the Phillies on June 30, Spinks was 5-4 with a 2.33 ERA and was being hailed, along with the Mets’ Jon Matlack, as a strong candidate for the 1972 National League Rookie of the Year Award.

“I’ve been in baseball 30 years and I’ve seen a lot come and go, but this guy Spinks is one of the greatest I’ve seen break in,” umpire Ed Sudol told The Sporting News. “Besides that fastball, he has a snapping curve.”

Reds coach Alex Grammas, the former Cardinals shortstop, said, “Spinks can throw as hard as Nolan Ryan and Bob Gibson.”

Former Cardinals third baseman Mike Shannon told the Tulsa World, “There aren’t many guys in the league right now who have the great, smooth stuff Spinks has.”

Wounded knee

On July 4 at Cincinnati, Spinks streaked from first base to the plate on a Luis Melendez double and slid into the shin guards of catcher Johnny Bench. The collision knocked the ball from Bench’s glove and Spinks was ruled safe, but he tore ligaments in his right knee. Boxscore

(“I don’t think a catcher ought to come down on you like that unless he’s got the ball,” Spinks told the Tulsa World.)

Spinks had knee surgery two days later and was done for the season. At the time of his injury, Spinks ranked third among National League pitchers in strikeouts, behind Carlton and Tom Seaver.

Years later, Ted Simmons told Cardinals Magazine, “Scipio had an extraordinary fastball that was absolutely in the upper 90s. He was in the top one percent tier of velocity … a dynamo on the mound … Scipio wasn’t fully mature yet, but he was getting there. he was very much the same kind of pitcher Reuss became once Reuss got his command.”

Spinks was 5-5 with a 2.67 ERA in 16 starts for the 1972 Cardinals. In his five wins, his ERA was 1.20 and all were complete games.

In 1973, Spinks returned to the Cardinals’ starting rotation, lost his first four decisions and then got a measure of revenge against the Reds, earning a win with six shutout innings. Boxscore

It would be Spinks’ last win in the majors. In June, he went on the disabled list because of a shoulder injury and was shut down for the season. In eight starts for the 1973 Cardinals, Spinks was 1-5 with a 4.89 ERA.

At spring training in 1974, the Cardinals traded Spinks to his hometown Cubs for pinch-hitter Jim Hickman. On his way out, Spinks gave “Mighty Joe” to Bernie Carbo, a former Cardinals teammate who was with the Red Sox.

Spinks never played in another big-league game. He tore a thigh muscle and spent the 1974 season in the Cubs’ farm system. His last season, 1975, was with minor-league teams of the Astros and Yankees.

Lance Clemons, the other pitcher acquired for Reuss, appeared in three games for the 1972 Cardinals and was traded to the Red Sox in March 1973.

Reuss played 22 seasons in the majors, primarily with the Pirates and Dodgers, and earned 220 wins. He was 14-18 with five shutouts versus the Cardinals.

On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash.

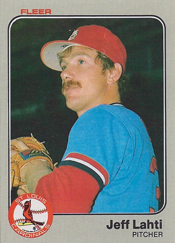

On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash. On April 1, 1982, the Cardinals acquired Jeff Lahti and another minor-league pitcher, Oscar Brito, from the Reds for big-league pitcher Bob Shirley.

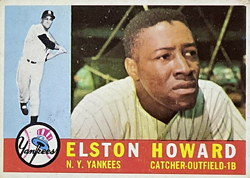

On April 1, 1982, the Cardinals acquired Jeff Lahti and another minor-league pitcher, Oscar Brito, from the Reds for big-league pitcher Bob Shirley. It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try.

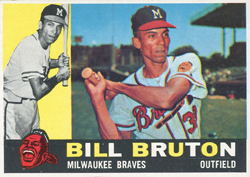

It was an audacious attempt, coming two months after a World Series in which Howard hit .462 and Ford pitched a pair of shutouts, but Cardinals general manager Bing Devine indicated the Yankees gave him reason to try. A left-handed batter, Bruton became the Braves’ center fielder in 1953 and helped transform them into National League champions in 1957 and 1958.

A left-handed batter, Bruton became the Braves’ center fielder in 1953 and helped transform them into National League champions in 1957 and 1958.  Green had successes, but his drinking held him back, and his recklessness had devastating consequences.

Green had successes, but his drinking held him back, and his recklessness had devastating consequences.